Thinking with Film: On John Carvalho’s reading of Godard’s Le Mépris

Deborah Knight

Abstract

In Thinking with Images, John Carvalho is especially interested in situations where we do not know what to think about a work of art — where it perplexes us, where we cannot find answers to the questions it raises. I will focus on Carvalho’s final chapter which discusses Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film, Le Mépris (Contempt), adapted from the novel by Alberto Moravia. I argue that Le Mépris is not primarily about its literary content involving the collapse of a marriage during the filming of an adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey. I recommend that instead we think about such things as Godard’s decision to cast Fritz Lang in the role of the director of the film-within-a-film, the contest between art and commerce represented by the American producer of Lang’s Homer epic, and Le Mépris’s network of allusions to a range of Hollywood and European films admired by Godard and the critics at Cahiers du Cinéma. Rather than thinking about Le Mépris in terms of its ostensible plot and themes, I argue that we should instead consider what it reveals about Godard’s thinking about the state of the cinema in 1963.

Key Words

Brecht; John Carvalho; Homer’s Odyssey; Jean-Luc Godard; Fritz Lang; Laura Mulvey; Cahiers du Cinéma; Cinécittà; peplum subgenre; Verfremdundseffekt

1. When we do not know what to think

John Carvalho’s premise in Thinking with Images is: “We really begin to think when we do not know what to think.” Most of the time, yes, we are thinking, but in a familiar, perhaps conventionalized, perhaps “rule-following” or problem-solving sort of way that allows us to arrive at a conclusion or judgment or action. That’s not the sort of thinking Carvalho is interested in. Rather, he is interested in what goes on when we are confronted by what is “unfamiliar or new to us” — something that might also be “captivating or strange” or “colored by uncertainty”.[1] He is especially interested in situations where we do not know what to think about a work of art, where it perplexes us, where we cannot find answers to the questions it raises. Carvalho recommends that we attend to the affordances the artwork itself provides, affordances that can assist us in the general task of making sense of the work. If we can define “an affordance” as “a relationship between the properties of an object and the capabilities of the agent” that determines, in our case, how the object could be understood, then our task is not to look elsewhere but to look at the work of art itself.[2] Rather than try to resolve our uncertainty by appeal to something outside the work — to some version of critical theory, for example — Carvalho encourages us instead to sit with our uncertainty, because, as he might say, this encounter provides us with the opportunity to “think without knowing what to think.”[3]

I will focus on the final chapter of Carvalho’s book, which deals with Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film, Le Mépris (Contempt). I will say a bit more shortly about how Carvalho approaches this most idiosyncratic of Godard’s oeuvre, but first I want to confess that when I first saw Le Mépris, I did not know what to think about it. Earlier in my career I taught in a Film Studies department. I have taught Hollywood films and art cinema films and films by Godard. I am comfortable with the many Brechtian distancing effects — Verfremdungseffekten — we find in Godard’s films: the disruption of seamless, linear-causal storytelling; the foregrounding of stylistic devices such as discontinuous editing, extended tracking shots, and the random use of filters or unconventional lighting techniques; the rejection of the idea that characters must be psychologically coherent in order for us to be able to identify with them emotionally; and, in general, all Godard’s strategies for drawing attention away from a film’s story and instead focusing us on the filmmaking process. Even so, Le Mépris initially struck me as deeply puzzling. Let me back up a moment.

2. “A film about film”

Le Mépris, at least on its surface, is a film about the making of a film and the collapse of a marriage. The film being made is an adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey, directed by a fictional Fritz Lang (played by Fritz Lang) and produced by Jerry Prokosch (Jack Palance), a brash American financier modelled on Kirk Douglas’s cutthroat movie producer in Vincent Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). Le Mépris is set in Rome and Capri, where the Homer adaptation is being filmed. Paul (Michel Piccoli) is the French screenwriter hired by Prokosh to turn Lang’s film from a meditative work of art cinema into a 1963-style Hollywood blockbuster. Paul’s wife, Camille — who, as played by Brigitte Bardot, is virtually indistinguishable from Bardot’s own star persona — has to ward off Prokosch’s sexual advances. Prokosch’s assistant, Francesca (Giorgia Moll), is thanklessly tasked with translating between the American and the Europeans in the film. Paul becomes too close to Francesca for Camille’s liking, but doesn’t intercede to protect her from Prokosch. By the second act of Le Mépris, it seems that Camille is falling out of love with her husband. In the film’s final act, after telling Paul that she feels contempt for him (“Je te méprise,” she says to him, also noted by Carvalho[4]), Camille leaves Capri with Prokosch, while Lang continues to film his Odyssey. Nevertheless, as Carvalho observes, “Le Mépris is not a film about lost love, though it is that, it is, rather, a film about film, about making a film.”[5]

Godard positions us between the film we are watching and the making of the film-within-the-film. The first half of the first act of Le Mépris fictionally takes place on the lot of the great Italian studio Cinécitta that in the film has fallen on hard times and which Prokosch claims he has sold. I say “fictionally takes place” since the actual filming location was the Titanus production company’s studio just outside Rome, which was in fact scheduled to be demolished at the time of the filming of Le Mépris. The next part of the first act occurs in a screening room at the fictional Cinécitta as Prokosh, Lang, Paul, and Francesca watch the rushes of Lang’s film. After a long second act that takes places primarily at Paul and Camille’s flat, itself still under construction in a new housing development in Rome, the film’s third act returns to the making of the Homer adaptation on the island of Capri, where Lang films the final shots of his Odyssey, which turn out also to be the final shots of Godard’s film.

Prokosh, the producer, has hired Lang for reasons of misguided cultural pretention, explaining that an adaptation of The Odyssey needs a German director since, as everyone knows, Schliemann discovered Troy. Lang appears to be making a film about grand humanistic themes: the eternal problems of the ancient Greeks, specifically the individual versus circumstances, as he explains. But Prokosh wants the Odyssey to be a box-office success. He wants action, not philosophizing. The struggle between Prokosch and Lang is the struggle between commerce and art. Concurrently, Godard’s own struggles with his producers, Carlo Ponti and Joseph E. Levine, are inscribed in Le Mépris. Prokosch, it is plausibly argued, is in part based on Levine, who insisted that Le Mépris be shot in Cinemascope, an aspect ratio that Lang pokes fun at as only being good for snakes and funerals. Although Le Mépris already contained some shots of Bardot semi-dressed or naked, Levine made Godard insert an additional scene of a naked Bardot into what had been the film’s final cut since, from a Hollywood producer’s perspective, the more time Bardot is naked on screen, the better for the film’s box office. The scene, shot with few edits and with overlaid filters, shows Bardot and Piccoli together in bed as Bardot, lying on her stomach, asks Piccoli whether he likes her body, listing parts of her body from her feet up to her face. As Roger Ebert wryly notes about this scene that Godard inserted immediately after the film’s opening credits as if to get it out of the way as early as possible, Godard gave his producers “acres of skin but no eroticism.”[6]

Godard exploits a range of distanciation effects in Le Mépris intended to, as Brecht once put it, prevent the film’s audience from “simply identifying itself with the characters.”[7] Nevertheless, like other early Godard films such as Breathless, Le Mépris, features charming naturalistic performances by Michel Piccoli, Fritz Lang, and Giorgia Moll. Yet at the same time, we have an eccentrically unnaturalistic performance by Jack Palance, whose first long speech takes place on a raised stage-like area as if he is declaiming to a theatre audience. Prokosch’s presence in the film, both physically and verbally, combines bombast, melodrama, and an element of danger. There are several beautifully blocked set pieces designed to make us think as much about how the actors are positioned in the frame and how they move within the film’s mise-en-scène as what they are doing or saying in the plot. These set pieces include several in the third act on Capri, but none is more fascinating than the main part of the film’s second act representing an extended conversation between Paul and Camille.

During the scene they move back and forth in their new flat, from the kitchenette to the dining area through the living room to the bedroom and back again, taking baths, changing clothes, setting the dinner table. This is the scene where Camille tries on a short black wig for the first time. Yet their dialogue, here as elsewhere in the film, is mundane, repetitive, contradictory; they do not so much talk to one another as talk past one another. The film’s poignant, melancholic theme music by Georges Delerue, which recurs frequently as an extra-diegetic commentary on plot action, seems designed to direct our emotional response to the film in particular ways that are undercut by, or at least in tension with, the Brechtian aspects of Godard’s style. Having seen and taught some of Godard’s traffic accidents and death scenes (Breathless, Weekend), I was unsurprised by the static and affectless staging of the scene that reveals that Prokosch and Camille have been killed in a car crash. The most disruptive aspect of the film, the one that most joltingly reminded me of the artificiality of the filmmaking process, was the screening of the dailies of Lang’s Odyssey — the film-within-the-film — that Prokosch, Lang, Paul, and Francesca watch in the first act of Le Mépris. This is where I experienced, in a profound way, what Carvalho describes as not knowing what to think.

3. Thinking about Le Mepris

So, what to think about Le Mépris? Carvalho and I take somewhat different paths. Carvalho starts with the literary sources of the film, in particular Godard’s “appropriation of the literary form of Moravia’s novel, Homer, and Hölderlin.”[8] Godard based his script on Alberto Moravia’s novel, Il disprezzo, about a young Italian author and sometime screenwriter who reflects on the collapse of his marriage over the course of his time revising the script for a film based on Homer’s Odyssey. In Moravia’s novel and Godard’s film, characters speculate about the psychology and motives of both Ulysses and Penelope: maybe she didn’t really love him, perhaps she was unfaithful, perhaps Ulysses stayed away so long because he didn’t want to return? Similar sorts of questions arise for Paul and Camille as their relationship unravels: does Camille love him or not? Paul rightly comes to suspect that what Camille feels is no longer love but rather contempt.

The thematic concerns that Carvalho focuses on include the discussion in the screening room between Lang and Francesca of the concluding stanza of “A Poet’s Vocation” (Dichterberuf), a poem by Hölderlin, one of Godard’s additions to Moravia’s original story. Speaking in both German and French, Lang and Francesca consider whether the poem offers us the comfort of knowing that the gods will look after man or the bleak recognition that the gods are absent from human affairs, as Lang suggests was Hölderlin’s meaning. These reflections set the stage for Carvalho’s consideration of “the affective quality of le mépris [contempt, indifference], this indefinite something that emerges from the concrete realities of the Mediterranean environs and film.”[9] He concludes the chapter with a discussion of the parallel between Godard’s opening credit sequence, shot in one extended take, and the film’s concluding scene, both of which feature “the filming of the filming of a film.”[10] In short, when Carvalho takes on the task of deciding what to think about Le Mépris, he begins from the perspective of the film’s literary genealogy, the main sources of its plot and dominant literary themes. By contrast, the issues raised by the film’s plot and themes, including those concerning le mépris itself, are not what I found especially puzzling. Rather, in an attempt to decide what to think about Le Mépris, I had to find a way to explain the images in the dailies of Lang’s Odyssey.

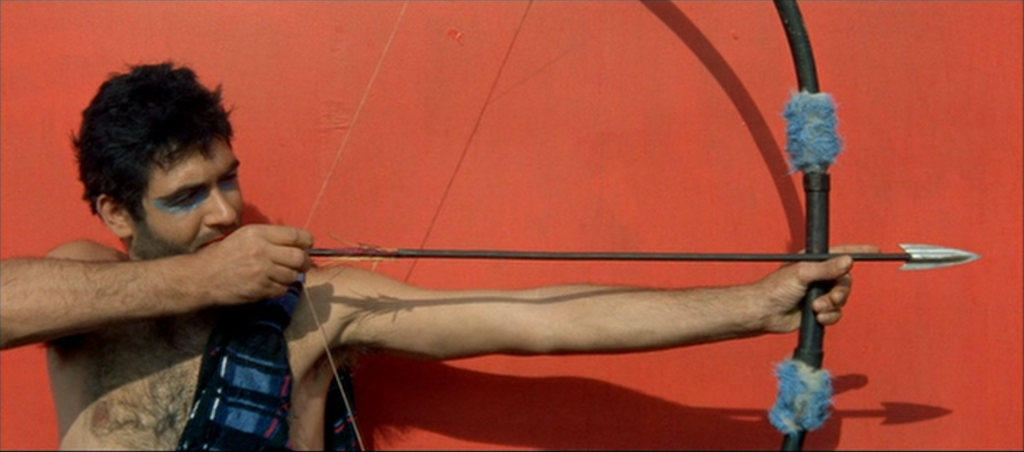

The dailies feature two kinds of shots: shots of statutes and shots of actors. The first image we see is of a white plaster statue, presumably Ulysses, with eyes painted blue and thin lips painted red, framed in medium close-up, as the camera subtly tightens its focus on the unseeing face. This shot is followed by a helmeted Minerva, with red-painted eyes, and then Neptune, with blue eyes and lips, based on the Artemision bronze statue of either Zeus or Poseidon. The second reel of dailies — Lang calls out, “Zweite” to his projectionist — continues with the statue of a woman, presumably Penelope; a shot of two statues with black-painted hair; three statues of women in classical poses positioned in a grassy field; a gold-colored bust of Homer; and finally shots of actual actors. The first actor is a woman seen from above swimming naked in the sea, followed by a close-up of a female actor standing against an ochre-colored wall. Up to this point, it is entirely unclear just what the function of these shots is intended to be. Why statues? Why a naked woman swimming in the sea? How do these shots fit into Lang’s vision of his Odyssey?

At this point in the dailies, we see an actual sequence of shots that follow one another so as to tell a minimal story. First, we are shown a male actor in ancient Greek costume holding a bow and arrow framed in a medium shot. Next, we see the female actor, also in a medium shot, who scans from left to right. Finally, there is a shot of a second male actor, also in Greek costume, with an arrow piercing his neck and fake blood flowing from the wound. There is no dialogue and only minimal motion. The actors in this short montage are as unnaturalistic as the statues we saw just before, the statues with their painted-on highlights, the actors in gaudy make-up. I was most perplexed by the shots of the plaster statuary and even more so when, later in the film, Godard inserts some of these shots from Lang’s Odyssey directly into the film we are watching about Paul and Camille. What to think about these images?

4. What Le Mépris is actually about

My search for an answer led me to film historian and theorist Laura Mulvey.[11] On Mulvey’s reading, Le Mépris is not primarily about its ostensible literary content. It is not primarily about the characters’ actions in the film’s plot, nor about the themes derived from Moravia’s novel, nor about the Odyssey, or the musings of Hölderlin, or Dante, who is also referenced in the film. Rather, she argues, the film is a “meditation” not on the loss of the gods or the existential emptiness of human existence but rather about “the crisis of the Hollywood studio system and its aftermath.”[12] This story, as Mulvey explains, is not told at the level of plot but at the level of “signs, images and allusions that reference the world of cinéphilia” — a world interested in films, film theory, and film criticism.[13] The world of cinéphilia is Godard’s world, the world of Cahiers du Cinéma and André Bazin’s politique des auteurs, which celebrated not only the great directors of the European cinema, including Renoir, Rossellini and Lang, but Hollywood directors including Hitchcock, Hawks, and Ford. Mulvey quotes the French film scholar Michel Marie: “The aesthetic project of Le Mépris is entirely determined by the context of the end of classical cinema and the emergence of new ‘revolutionary’ forms of narrative.”[14]

While Le Mépris is a film about filmmaking, as Carvalho also argues, and while it contains the range of themes Carvalho discusses, at the same time it is a film about the state of the cinema in 1963. It is about what Godard knows from his time as a critic writing for Cahiers and also from creating his innovative New Wave films, including Breathless (1960), A Woman is a Woman (1961), and Vivre sa vie (1962). Le Mépris is a tapestry of allusions to other films. These allusions can be seen in posters on the walls of different settings and in the composition of shots, the details of costuming, and Godard’s color scheme. Thinking about Le Mépris as being about its network of allusions opened up a new set of meanings and helped me solve my initial puzzlement about the dailies from Lang’s Odyssey.

Many of the key allusions are located in the film’s cast, starting with the great German director Fritz Lang, whose career began in German silent cinema (Metropolis, 1927) and continued in Hollywood after he escaped Weimar Germany. Paul explains Lang’s escape from Germany in 1933 to Camille in the film’s first act. Giorgia Moll, as Francesca, connects Le Mépris back to Joseph Manikewicz (All About Eve, 1950), a director beloved by Cahier, and his adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American (1958), in which she starred. Moll’s character in Le Mépris, Francesca Vanini, references Rossellini’s Vanina Vanini, a film made just two years earlier. Vanina Vanini is one of the films whose poster features prominently in the first act of Le Mépris. And of course by casting Bardot, Godard alludes to her iconic status as a sex symbol and thus to every role she has previously played, including in Robert Wise’s Helen of Troy (1956) and Roger Vadim’s Et dieu…créa la femme (1956).[15]

A second set of allusions concerns the state of Hollywood in the 1950s and early 1960s. The collapse of the great era of the Hollywood studio system was signaled by both the advent of black-and-white television that kept audiences at home and the rise of a certain type of blockbuster intended to bring audiences back to film theaters. This new type of blockbuster was often filmed in Europe, typically around the Mediterranean, often set in ancient Greece or Rome or the Holy Land, typically featured heroic exploits, and was filmed in color (often Technicolor) and in wide-screen (often Cinemascope). These sword-and-sandals blockbusters — the peplum genre, named after the short tunics worn by our swaggering, muscled, and oiled leading men — became a staple feature of Hollywood-financed production and distribution, often in conjunction with Italian studios, in the 1950s. Key titles include: The Robe, starring Richard Burton in one of his first leading Hollywood roles (1953) and its sequel, Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954); Hercules, starring Steve Reeves (1958); William Wyler’s Ben-Hur, featuring Charlton Heston and Stephen Boyd (1959); Spartacus, starring Kirk Douglas (1960); and Barabbas, starring Anthony Quinn (1961). In 1954, Carlo Ponti, one of Godard’s producers for Le Mépris, produced both the sword-and-sandals blockbuster, Ulysses, starring Kirk Douglas, and Fellini’s art cinema classic, La Strada, with Anthony Quinn in leading roles in both films. Jack Palance had himself just completed a string of sword-and-sandals blockbusters in the years immediately prior to Le Mépris, with leading roles in The Barbarians (1960), Sword of the Conqueror (1961), and The Mongols (1961), all shot on location in Italy and all either Italian-American co-productions or Italian-produced films handled by American distributors. While Godard was making Le Mépris, the great Joseph Mankiewicz was directing Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in Cleopatra, itself a sword-and-sandals blockbuster shot at various locations in Italy, including at Cinecittà. Clearly, one thing that Le Mépris is about is the sword-and-sandals or peplum genre. These were the fantasy-action films of the pre-CGI period. This is the sort of film that Jerry Prokosch wants Fritz Lang to make and the reason he hires Paul to revise Lang’s script.

In contrast to this string of allusions, Le Mépris also calls attention to films admired by Godard and Cahiers. The color palette of Le Mépris, which emphasizes white along with the three primaries (mostly red and blue until yellow appears prominently in the third act), harkens back to the color palette of Otto Preminger’s Bonjour Tristesse (1958).[16] The close-ups of ancient statues of Minerva and Neptune that feature in Lang’s dailies recall a key scene when Ingrid Bergman visits the historical museum in Naples in Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (1954), also a film about a married couple who realize they have fallen out of love with one another. In case we might miss this reference, toward the end of the second act of Le Mépris our characters leave a theatre advertising Viaggio in Italia, with a large poster affixed to the cinema’s wall and the title in bold letters on its marquee. But visual references to films begin even earlier in Le Mépris. When Prokosch, Lang, Paul, and Francesca leave the screening room in Act One, they walk down a street on the studio backlot in front of a wall plastered with large film posters: Howard Hawks’s Hatari (1962), Godard’s Vivre sa vie (1962), Rossellini’s Vanina Vanini (1961), a second poster for Hatari, and Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). These are the films and directors admired by Cahiers. Later in Le Mépris, when Camille puts on the bobbed black wig over her signature long blonde hair, we see a reference to Godard’s muse and partner, Anna Karina, whose hair was worn that way the year before in Vivre sa vie, as we can see in the poster.

References to Hollywood cinema occur in the film’s dialogue too. For example, when Bardot, as Camille, appears for the first time in the scene on the studio backlot, Paul introduces her to the great Fritz Lang. They say how much they admire his “Western with Marlene Dietrich” (Rancho Notorious, 1953), almost without recognizing how Lang’s filmmaking career had to change to fit into the generic expectations of Hollywood. Lang’s dry reply, that he prefers M (1931), his dark classic of German Expressionism starring Peter Lorre as a serial child killer, recalls his period of greatest cinematic inventiveness before arriving in Hollywood. And, speaking of allusions, it is worth mentioning that M made innovative use of long tracking shots and featured a repeated, melancholic musical theme, both stylistic devices used by Godard in Le Mépris. Griffith and Chaplin, Nicholas Ray and Howard Hawks, are all referenced, as Carvalho also notes.[17] In the film’s second act, when Camille asks Paul why he insists on wearing his hat even in the bathtub, Paul explains it is his homage to Dean Martin in Vincent Minnelli’s Some Came Running (1958), even though Paul’s hat looks more like Belmondo’s in Breathless than Martin’s. As Mulvey argues, Le Mépris is about the state of the cinema in 1963 as set out by the network of allusions presented in the film’s images.

5. The significance of Fritz Lang

To come back to my original perplexity: what to make of the film the fictional Fritz Lang is directing and, in particular, what to make of the dailies that, as Mulvey notes, seem to be “snippets of [a] story composed more in tableaux than in continuity.”[18] These shots of statues of the Greek gods make no sense in the fictional world of Le Mépris. As already noted, Godard later edits shots of the statues portentously into the story of Paul and Camille. Taken together with the mostly static shots of the actors in ancient Greek costume, with too much make-up on, we are led, I think, to the conclusion that Hollywood’s enfranchisement of the peplum film, which I’m calling here the sword-and-sandals blockbuster genre, is the real focus of Godard’s mépris: that is, the real focus of both his film and his contempt. But the kind of esoteric art cinema full of high-minded but largely inscrutable historical and cultural references of the sort that the fictional Fritz Lang is crafting will not be the way forward for the cinema either. On the wall of the screening room at Cinécitta, under the screen on which the dailies are projected, is a quote from Louis Lumière, that I translate from the Italian appearing in the film: “The cinema is an invention without any future.” In 1963, under the control of interfering box-office-oriented producers working within what remains of the Hollywood system, the future of the cinema is at least not obvious.

Carvalho argues that if there is a hero in Godard’s film, it is Fritz Lang, and certainly Godard’s admiration for Lang is well-established. Indeed, Godard cast himself as Lang’s fictional assistant for the final scene of the film. Yet, as Yasuko Taoka observes, Lang functions in Le Mépris as “a giant of the previous generation.”[19] I would argue that Le Mépris is a film without a hero, that heroes are relics of a previous cultural epoch or, should we say, are only characters in certain genres of film. Even Ulysses, the protagonist of Lang’s film-within-a-film, is not a heroic figure. He is clearly an actor dressed in peplum carrying aloft a sword. In the film’s improbable and faintly absurd final shot, he is tracked moving laterally — literally, sideways — at the edge of the stage atop the roof of the villa on Capri, overlooking the Mediterranean and the horizon, where sea meets sky. Even Fritz Lang cannot successfully reinvent the sorts of peplum narratives which have been co-opted by Hollywood.

I want to thank John Carvalho for making me think about Le Mépris. Our interpretative paths have taken us in some different directions. I think Hume would put this down to differences in temperament. But in conclusion, I want to say that Carvalho is right about the significance of Lang for Godard’s film, although not because Lang is the film’s hero. The tragedy of Le Mépris is not the collapse of a marriage or the death of Camille and Prokosch; these are just matters of fiction. Rather, the tragedy is that in the final years of his career, in the late 1950s, Lang had himself been reduced to making B films featuring has-been actors. Four years before Le Mépris and among his very last films, Lang had directed Debra Paget, never a major star herself and in the waning years of her career, in The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb (both 1959), low-budget genre films shot all but simultaneously and set in an exotic locale. Without any participation by Lang, the American distributor API used footage from both to produce Journey to the Lost City (1960), a film packaged as part of a double bill for small cinemas and drive-ins aimed at teenage audiences. Lang’s last films were bought by close to twenty distributors worldwide, offering no major theatrical release because the distribution rights were invariably used for television rentals and video sales. Godard has emblematized this tragedy in Le Mépris, where Fritz Lang, one of the most influential directors in cinematic history, the director of Metropolis and M and, yes, Rancho Notorious, is reduced to directing a peplum film for a crass American producer interested in box office returns, not art.

Deborah Knight

knightd@queensu.ca

Deborah Knight is Associate Professor of Philosophy and Queen’s National Scholar at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. She writes primarily about the narrative arts including literature and film, as well as about our emotional engagement with works of narrative and visual art. Her “The Proper Object of Emotion: Memorial Art, Grief, Remembrance,” was recently published in Philosophical Perspectives on Ruins, Monuments, and Memorials, eds. Bicknell, Judkins, and Korsmeyer.

Published January 27, 2022.

Cite this article: Deborah Knight, “Thinking with Film: On John Carvalho’s reading of Godard’s Le Mépris,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Volume 20 (2022), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] John M. Carvalho, Thinking with Images: An Enactivist Aesthetics (New York: Routledge, 2019), p. 1.

[2] Don Norman, The Design of Everyday Things (New York: Basic Books, 2013), p. 11.

[3] Thinking with Images, p. 4.

[4] Ibid., p. 133.

[5] Ibid., pp. 130-131.

[6] Roger Ebert, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/contempt-1997.

[7] Bertold Brecht, Brecht on Theatre (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), p. 91.

[8] Thinking with Images, p. 121.

[9] Ibid., p. 119.

[10] Ibid., p. 140.

[11] Laura Mulvey, “Le Mépris (Jean-Luc Godard 1963) and its story of cinema: a ‘fabric of quotations,’” in Godard’s Contempt: essays from the London Consortium, eds. Colin MacCabe and Laura Mulvey (London: London Consortium, 2012), and “The Decline and Fall of Hollywood According to Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris,” in Afterimages: On Cinema, Women and Changing Times (London: Reaktion Books, 2019).

[12] Mulvey, “Decline and Fall of Hollywood,” p. 72.

[13] Ibid., p. 72.

[14] Mulvey, “Le Mépris,” p. 227.

[15] Carvalho discusses Bardot as icon and Godard’s Cahiers reviews of her films (Thinking with Images, p. 123).

[16] A point made, for example, by John Patterson in his reconsideration of Bonjour Tristesse, in The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/film/2013/aug/26/otto-preminger-bonjour-tristesse-john-patterson.

[17] Thinking with Images, p. 129.

[18] Mulvey, “Le Mépris,” p. 230.

[19] Yasuko Taoka, “(Be)Coming Home(r): Nostalgia in Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt,” Arthusa, 45, 2 (2012), p. 250.