The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

In-Between Places: Richard Long’s Walk-Works on Dartmoor and in Japan

Eriko Yamaguchi

Abstract

Contemporary British sculptor Richard Long creates sculptures for places that he encounters during walks. Each sculpture is place-specific, but rather than separating one place from another, a Long sculpture, besides connecting places, also creates a place in the in-between spaces. Long notes that his landscape sculptures “are out there in the world, somewhere.” His work engages directly with the materials that constitute those in-between places as a mark of his being on his way. His sculptures thereby encompass time, space, speed, the distance of his walk, his physical reality, and sensory experiences encountered during his walks. These will, however, soon disappear or disperse, but his walk continues and is never completed. Such walk-works challenge the received wisdom that a canonical sculpture must be a visual form of material weight and permanence. He also makes his works a counterpoint to the contemporary world, where walking is primarily a means to an end. The goal-directed notion of transport and the network of point-to-point connections neglect the experience engendered in the in between and thereby diminish it. This paper explores Long’s walk-works in the in-between places to reconsider rich meanings in a transitional space and time, somewhere, nowhere.

Key Words

Dartmoor; experience; in-between places; Japan; Richard Long; walk-works

A footpath is a place.

It also goes from place to place, from here to there, and back again.

Any place along it is a stopping place.[1]

1. Walking in between places

Anthropologist Tim Ingold traces visible and invisible lines that human beings, animals, insects, and plants leave when they move on their way. He claims in his Lines: A Brief History (2007) and The Life of Lines (2015) that our lines are meandering and curvilinear, entwining with those lines left by the others, and make up a “meshwork.” Nowadays, as we tend to use transport oriented to a specific destination, the modern world sets a high value on the network of point-to-point connections, in which each line starts at A and ends at B; but in contrast, lines of the meshwork have no beginning or end. Entwining with other lines at the knot, the lines of the meshwork go somewhere, as they move along in a labyrinth.[2] Ingold contrasts the wayfarer who walks in a labyrinth to the navigator who moves toward a destination: “In the carrying on of the wayfarer, every destination is by the way; his path runs always in between. The movements of the navigator, by contrast, are point-to-point, and every point has been arrived at, by calculation, even before setting off towards it.”[3] Since the wayfarer walks always in between, he or she “is always somewhere”:

While on the trail the wayfarer is always somewhere, yet every ‘somewhere’ is on the way to somewhere else. The inhabited world is a reticulate meshwork of such trails, which is continually being woven as life goes on along them.[4]

Ingold uses the term ‘meshwork,’ which means “an entanglement of interwoven lines,” borrowing from Henri Lefebvre’s remark about the paths that form “the reticular patterns left by animals, both wild and domestic, and by people,” in La production de l’espace (1974).[5] Inhabitants’ lives shape the tangled and interwoven lines that weave the meshwork, threading their ways “through and among the way of every other,” as every animate being does.[6] In threading our ways, we engage directly with other beings, materials, and the world.

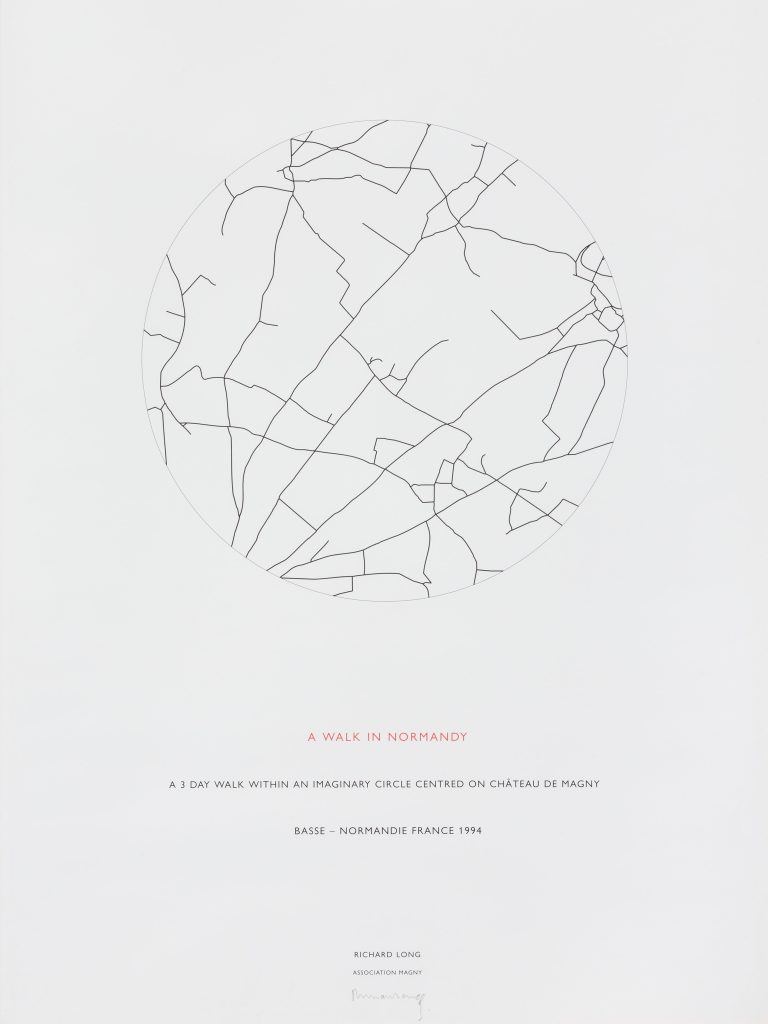

Like Ingold, Long finds “[t]he line of the walk” as “the exact shape of the land, it is a unique undulating section” or “a portrait of the country.” To walk over the land is “to walk over the shape of the land” and “to walk over the pattern of the roads.” If we look down a road that goes over the contours of the land, it makes “the pattern of a social and historical system of travelling, linking villages, going around fields.”[7] This pattern is precisely what Ingold argues is a meshwork. As Long’s text-and-line work of Walk in Normandy (1994) (Fig. 1)[8] reveals, his trace of walking along the roads in Basse-Normandie weaves a meshwork. Circles are knots of the meshwork.

Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Libraries and Museums, ID: HC2009.17(3)

©️ Richard Long. All rights reserved, DACS & JASPAR 2024 G3452

However nowadays, the meshwork, as Ingold states, is overridden by the network of point-to-point connections. The transported traveler is thereby moved from place to place, without direct physical engagement with the surroundings along the way. The traveler also does not appreciate experiences of the sights, sounds, taste, smells, and touch that the journey might otherwise afford. In this journey of the network, the “in-between” place is made invisible and transparent, and immediate experience of places and materials available there has no bearing on the transition.

Byung-Chul Han also argues that, similar to the path of a pilgrimage, the state of being on one’s way is not an empty space between two places, but rather an interval full of meaning:

The pilgrim’s path is not merely a thoroughfare, but a transition to a There. In temporal terms, the pilgrim is on the way to the future, which is expected to bring salvation. To that extent, he is not a tourist. A transition is an alien notion to a tourist for whom everywhere is Here and Now. A tourist is not on the way in the proper sense.[9]

Han warns us that “today’s experience is characterized by the fact that it is very poor in transitions.” The “threshold” rich meaning is lost by pure orientation towards the goal.[10] He finds in thresholds “the topology of passion,” which embraces both suffering and hope, loss and promise, and fear and expectation. The in-between spaces and times also have “the function of ordering and structuring,” which “structure[s] not only perception, but also life.”[11] A direction, that intervals provide, produces a meaningful sequence, a continuation. Without an interval of space and time, therefore, unstructured, directionless, and fragmented events begin and end without any continuity, duration, or transitions.

Traces in the transition to a There are not straightforward, but tangled like threads and take various forms. Dogs leave their paw prints in the mud. Earthworms leave traces of their body movements. The vines of a morning glory entwine. Human beings leave their traces on various surfaces of the earth. Ingold refers to Long’s A Line Make by Walking, England (1967)[12] as an example of traces made by human beings.

In 1967, Long took a train from London’s Waterloo Station, heading southwest. He got off at a station in the open countryside and found a field. In the field, he walked back and forth until the traces of his walking became a line. Then he took a photograph of the line he had made. In making this work, Long realized, as Rudi Fuchs remarks, that “walking slipped into line, line slipped into form, form slipped into place, place slipped into image.”[13] In 2000, he explained his first walk-work as follows:

My first work made by walking, in 1967, was a straight line in a grass field, which was also my own path, going ‘nowhere’. In the subsequent early map works, recording very simple but precise walks on Exmoor and Dartmoor, my intention was to make a new way of walking: walking as art. Each walk followed my own unique, formal route, for an original reason, which was different from other categories of walking, like travelling.[14]

Long’s path on the grass goes “nowhere.” In this sense, his walks are never completed; they remain unfinished and continue, the mode of which is opposite to goal-directed or telic transport. Indeed, Long writes, “I have made walks within a place as opposed to a linear journey; walking without travelling.”[15]

In the following sections, I will explore Long’s walk-works as the art of going “nowhere,” which produces works in the between places and re-evaluates the meaning of the in betweenness. From somewhere to somewhere, Long carries, kicks, or lifts available stones or sticks to arrange them in a line or a circle. In handling them, he makes a direct engagement with these materials and the environment. Blue skies, clouds, rain, snow, and wind are his company. Sights, sounds, scents, taste, atmosphere, and feelings accost him during his walk, and such sensory experiences, that are almost neglected in the goal-directed transport or the point-to-point network are found to be involved in his works.

It was on Dartmoor, South Devon, in England, where Long made walk-works in many ways to produce new art. From this home landscape, his walk extends over the surface of the earth. Long admits that his home landscape and exotic places are “complementary.”[16] Japan is one of the most inspiring places for Long to walk. We will trace how Long finds places for his walk-works on Dartmoor, how the place extends to the in-between places, and how he recognizes Japan as a place somewhat complementary to Dartmoor. Between the places—between perfection and imperfection, permanence and disappearance, and visibility and invisibility—a “threshold” landscape will appear.

2. Sculpture as a place somewhere

During the walk, as visible marks of his invisible walks, Long makes lines or circles of stones or sticks, or piles of stones, in short, the materials he finds on his walk. He calls them “sculptures.” They are impermanent and will disappear after a short time. As stones or sticks are exposed to the rain, wind, and snow, and circles, lines, and piles collapse, the sculpture itself would disperse or disappear, or rather return to nature as time passes. What is important for Long is to create a sculpture in a place in his walking; in his own words, written in “Words After The Fact” (1982): “Time passes, a place remains. A walk moves through life, it is physical but afterwards invisible. A sculpture is still, a stopping place, visible.”[17] His sculptures are recorded permanently and shown to the public in the photographs Long takes. The visibility of the sculpture in the photograph contrasts with the inference from it that the work is now nowhere and invisible, except in its photographic record. In that sense, Long admits that his sculptures can elude artistic categorization:

A pile of stones or a walk, both have equal physical reality, though the walk is invisible. Some of my stone works can be seen, but not recognised as art.[18]

Long’s sculpture is quite challenging in terms of what is expected of sculpture canonically. Long does not intend to make permanent sculptures:

It is never my intention that these landscape sculptures remain permanently, or become known sites to be visited. Rather, that they are out there in the world, somewhere, perhaps to be seen by chance by locals, or even nobody at all.[19]

Long emphasizes “the freedom to use precisely all degrees of visibility and permanence.”[20] He says again, “In general, my work is about leaving or making my mark, with wide variations of permanence or visibility, like footprints or hand prints.”[21] Rudi Fuchs remarks that at the heart of Long’s works lies a “principle of ‘disappearance.’” In conversation with her, Long confessed that “he liked many of his works to be impermanent. That way they were more human, their limited physical existence in the world resembling the impermanence and reality of human life.”[22] This “principle of ‘disappearance’” is “against the dominant belief in most cultures that art is not only there to be used and enjoyed in the present but should also promote that present into an eternal future.”[23] Long challenges this belief with his walk-works and makes new art based on the freedom to use all degrees of visibility and permanence.

While walking, Long gradually gets “the rhythm of the walk” and starts “to be absorbed into the place.”[24] Then he makes sculptures for the place. The place, however, is not a goal of his walk, but somewhere on the path along it. The work does not separate the place from another place, but rather connects places—not only the named places, but also the unnamed places along the path of the walk—through his continuous walk and his walking body. His sculpture is made somewhere in the in-between spaces, involving his direct engagement with the materials that constitute these places. The in-between places embrace the interval sensations, as shown in his text work Spring Walk.[25] Somewhere in the in-between places, between primroses at 3 miles and frogspawn at 18 miles, Long walks and finds something. The visible invites the invisible, and vice versa.

In the in-between place, Long makes sculptures with stones or sticks, as he writes, “I like common materials, whatever is to hand, but especially stones.”[26] His sculpture discloses his physical movement while handling them. Although his walk, as Paul Moorhouse argues, “has no permanent physical attributes,”[27] Long highlights the in-between place by using common materials with his body and makes it physical, visible, and meteorological, albeit short in duration. Long emphasizes the “physical reality” and experience involved in his sculptures, as he writes, “My art is the essence of my experience, not a representation of it.”[28] Ben Jacks argues that Long’s pursuit of the immediacy of experience in art was influenced by John Dewey’s theory of “art as experience” and that “Long seeks to create works of art that affect us as they affected him when he made them.”[29]

3. Dartmoor: a home ground

Long praises Dartmoor, his “‘home’ ground,” not only for its abstract landscape as a “very beautiful, empty, flat place,” but also for its historical landscape as “a place of regeneration, knowledge, history and continuity.”[30] The moorland is known for granite tors, and the prehistoric menhirs and stone circles date back to the Neolithic and early Bronze Ages.

The abstract landscape of Dartmoor enabled Long to “construct” time, speed, and distance to visualize his idea and walk. His map work, A Walk of Four Hours and Four Circles, England (1972), shows four concentric circles.[31] Long walked each circle in an hour to realize his metrical idea. He first walked the inner circle, then the others with increasing speed. The four circles are a visual expression of his invisible walking time, speed, and distance, and the symmetrical numbers of “four” gives a frame to his walk. From the form and frame, we can imagine his bodily experience of the landscape, and even his fatigue, during the four walks. His circles are abstract in form, but physical in the actualization of his idea.

The historical landscape of Dartmoor stimulated Long to undertake work that focuses on the accumulation of time, distance, sensations, and memories. The tors and stones on the moor embrace the accumulation of immeasurable time. For Long, each thing has its own time and history, as the text work, Dartmoor Time: A Continuous Walk of 24 Hours on Dartmoor, reveals.[32] The rhythm of his walking accommodates these various histories of things. In the dry summer of 1976, Long completed A Hundred Tors in a Hundred Hours: A 114 Mile Walk on Dartmoor, Devon 1976.[33] Below a photograph of a tor are listed the names of 100 tors he reached in 100 hours, as if each tor is piled up. The work exposes the vast amount of distances and amount of time Long walked on the moor. This work reflects Long’s words in “Five, six, pick up sticks/ Seven, eight, lay them straight” (1980):

A walk is just one more layer, a mark, laid upon

the thousands of other layers of human

and geographic history on the surface of the land.Maps help to show this.

A walk traces the surface of the land,

it follows an idea, it follows the day and the night.[34]

On the surface of Dartmoor, Long began to pile up stones as “sculpture.” Long regards his sculptures as “places.”

My outdoor sculptures are places.

The material and the idea are of the place;

sculpture and place are one and the same.

The place is as far as the eye can see from the sculpture.

The place for a sculpture is found by walking.[35]

The sculpture is a marker for a particular place. Long expects that the photograph of the sculpture or the text work “feeds the imagination by extension to other places.”[36] The particular place extends to other places in the imagination; in other words, the place is to be somewhere in the in-between places.

On Dartmoor, Long recorded his walking time, speed, and distance in various permutations and symmetrical numbers, as the titles of his works show. Permutations of the numbers are the frame to make his walk and the in-between places and time visible and perceptible for the viewer of his photographs, maps, and text works, while rendering Long’s sensory experiences of nature into an aesthetic form. He remarks this in his own words:

I like to use the symmetry of patterns between time,

places and time, between distance and time,

between stones and distance, between time and stones.[37]

Clarrie Wallis points out that Long’s reading of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, as a student in Bristol in the early 1960s, invited him to “the relationship between all things.”[38] Long’s use of the symmetry of the patterns in time, places, distance, and stones is an attempt to embody this relationship on the earth through his walking body.

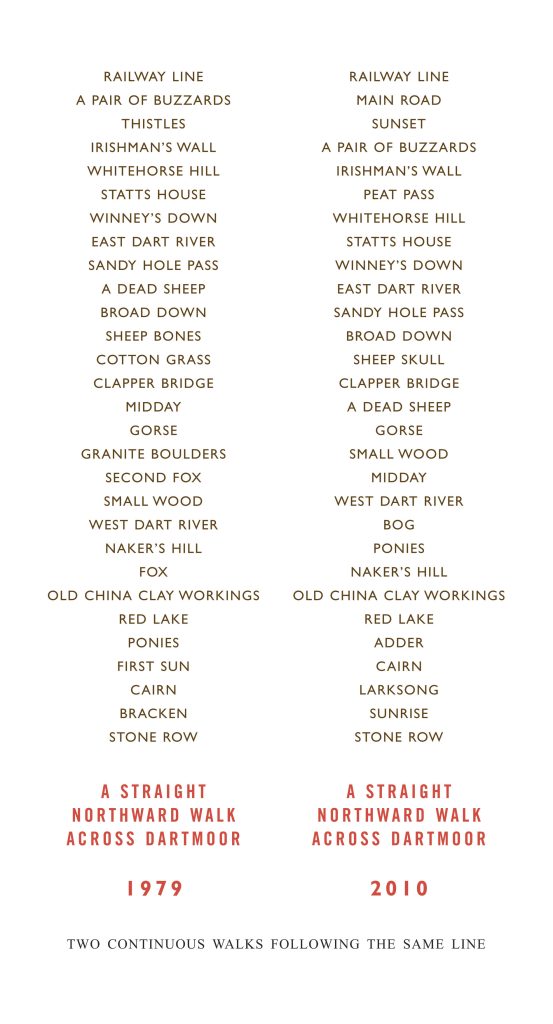

From the 1980s, Long accumulated the words of the things he encountered in his walking as text works. Wallis observes that “Long gave the text equal status with a photograph as an alternative means through which to represent a particular sculpture or walk.”[39] In an interview in 1995, Long said, “All those sculptures are the result of being on a walk. Each one is a relatively simple celebration of being in a particular place, at that moment, on a walk, almost like a poem or a song.”[40] The “poems or songs” of the place relate to each other and engender a “narrative” in the in-between places. Wallis cites Long’s description of his text works in his letter to her as “narratives of events and sculptures—walks—that I have made.”[41] A Straight Northward Walk Across Dartmoor, 1979-2010 (Fig. 2) shows the things and animals Long met when he walked northward on Dartmoor. Long again made the text work of the same title in 2010.[42] The words are arranged upwards in a line. We are expected to read the words from bottom to top, following his walks. The two lines of the words, recorded during walks in the same place in 1979 and in 2010, respectively, celebrate the in-between time.

Textwork ©️ Richard Long. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023.

Photo: Richard Long ©️ Richard Long. All rights reserved, DACS & JASPAR 2024 G3452

4. A Hundred Mile Walk

The arrangement of the stones as a sculpture is indeed the rearrangement of the place, as Long states, “These works are made of the place, they are a re-arrangement of it and in time will be re-absorbed by it. I hope to make work for the land, not against it.”[43] His sculptures are “a re-arrangement of” the place. The rearrangement heightens the sensation of the place and, consequently, celebrates the in-between spaces and times. Long admits that some of his works are indeed “a succession of particular places along a walk.”[44] The place is not a destination but a route between places, as Fuchs rightly describes as follows:

In principle, a walk could traverse different landscapes, at different times of day and night, in different conditions of weather and through different states of mind on the part of the walker—thereby making all these aspects of the real world part of the sculpture. The sculpture became a part of the world, an articulation of it—not an addition, not a stable object.[45]

The sculpture is intended to disperse and be invisible in the place, but the walking distance and time and even the walker’s physicality are to be transferred to other sculptures. The invisible and the visible thus overlapped somewhere along his walk between the places.

At New Year 1971-72, on Dartmoor, Long made a work, entitled A Hundred Mile Walk,[46] for which he walked repeatedly over a circular route for seven days. The work has a map showing the circular route he walked on Dartmoor, a photograph he took on the walk, and a text that recorded his sensory and physical experience of the sight, sound, and taste and the interaction of his feet and the earth during the walk. As the days passed, the route became more familiar and his perception became more heightened. On Day 1, he recorded a north wind, on Day 2, he felt the earth turn under his feet, and on Day 3, he sucked icicles from the grass stems. On Day 4, he felt as though he had never been born. On Day 5, he heard the sounds of rivers, and on Day 6, he heard “Corrina, Corrina,” sung by Bob Dylan. On Day 7, he wrote “Flop down on my back with tiredness, Stare up at the sky and watch it recede.”

Two years after this work, Long began his series, A Hundred Mile Walk, first in Ireland, next in Australia, then in Canada, and Japan (A Hundred Mile Walk Along a Line in County Mayo, Ireland (1974); A Hundred Mile Walk along a Straight Line in Australia, Returning to the Same Campsite Each Night (1977);[47] The High Plains: A Straight Hundred Mile Walk on the Canadian Prairie (1974);[48] and A Straight Hundred Mile Walk in Japan: Made Across a Mountainside on Honshu (1976)[49] [Fig. 3]). Of the series, he explains:

In the 1970s, I had the idea to walk exactly one hundred miles, up and down, back and forth, in a straight line, in different landscapes around the world. The first was across the boggy mountains of the West of Ireland, the next the red outback of Australia, the next the High Plains of Alberta−walking on a sea of grass, and lastly in a bamboo forest in Japan. The idea was that the straight walk, the one hundred miles, stayed the same, but the places, the landscapes, changed.[50]

©️ Richard Long. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photo: Richard Long

©️ Richard Long. All rights reserved, DACS & JASPAR 2024 G3452

Long experiences different states of mind and different conditions of his body in different landscapes on different ground surfaces along his way. The very dynamics of the ground and landscape drive him to walk on. In the series, Long did not make sculptures, but took photographs of landscapes, focusing on different grounds he walked on. He had direct engagement with the ground surface textured by diverse materials. In County Mayo, he walked the “boggy” ground. In the Red Centre of the Australian Outback, he walked the hard ground along a line, meeting a kangaroo on the way. In Canada, he walked “on a sea of grass” in the vast prairies under the cloudy sky. He is the only one in the earth-sky world. In Japan, he walked on ground covered with fallen leaves and branches through the eerie bamboo forest. Trees in the foreground are dead and broken, and in the background, they appear in the fog.

Although the photographs of the series, A Hundred Mile Walk, do not record his footprints, we can imagine from our own experience how he walked on the different grounds and how the footprints appeared. Ingold argues that footprints would vary “at the interface between the walking body and the ground.” “The ground … is matted from diverse materials. Footprints are impressed in the mat.”[51] Not on the mat, but in the mat, plants grow and die, animals breathe and move, and stones gather and scatter. In this sense, as Ingold argues, “the earth is perpetually growing over.” He continues,

thanks to its exposure to light, moisture and currents of air⏤to sun, rain and wind⏤the earth is forever bursting forth, not destroying the ground in consequence but creating it. It is not, then, the surface of the earth that maintains the separation of substances and medium, or confines them to their respective domains. It is rather its surfacing.[52]

Surfaces vary in relation to light, weather, water, air, and the pressure of touch. These surfaces are “in the world, not of it,”[53] and also stand between earth and sky. To live on the ground surfaces in the world is to exist between earth and sky. Long walks, surfacing, between earth and sky, as he writes in the text work Anywhere: An Eleven Day Winter Walk (2008).[54] He walks through stones, rivers, stars, mist, bones, flowers, wind, horizons, and the kindness of strangers.

Archaeologist Christopher Tilley also remarks on the differences of the surfaces that he walks on in his exploration of the relationship between the walking-body and the landscape:

To walk is to adopt different bodily postures, sometimes upright, sometimes bent, sometimes looking up, sometimes looking down. This is, in turn, related to the surfaces on which I walk and their characteristics: hard or soft, dry or slippery, even or stony, flat or rising or falling, firm or boggy…. My calf and leg muscles sense and register various degrees of energy and strain. These direct sensory relations engage my body as part of the landscape.[55]

Different grounds heighten Long’s awareness of the walking experience. Without such a text on his sense of awareness, as he wrote in A Hundred Mile Walk on Dartmoor, the series of A Hundred Mile Walk evokes his pungent perceptual landscape, the atmospheres of the place, and the walker’s feelings, shared with us. Such a walk can be compared to what Tilley writes of a “phenomenological walk”:

It is an attempt to walk from the inside, a participatory understanding produced by taking one’s own body into places and landscapes and an opening up of one’s perceptual sensibilities and experience. Such a walk always needs to start from a bracketing off of mediated representations of landscapes and places. It is an attempt to learn by describing perceptual experiences as precisely as possible as they unfold during the course of the walk. As such, it unfolds in the form of a story or a narrative that needs to be written as one walks.[56]

Walking a landscape gathers together through the walker’s body “its weathers, its topographies, its people, histories, traditions, and identities.”[57] Walking thus fuses the past with the present. Through this walk, a personal experience of walking links with others’ walks “beyond the autobiographical self.”[58]

While Long is conscious of English culture in his walk and sensibility,[59] as Michael Compton remarks, “he is not concerned with autobiography.”[60] In the series, A Hundred Mile Walk, he extended his walking to different grounds of the earth outside Britain and shared it with people beyond his own personal and cultural boundaries. Through his record of both his heightened perceptual engagement with external landscapes and his internal feelings during the “phenomenological walk,” his personal experiences are exposed to others in the form of a poem, a song, or a narrative that his invisible footsteps sing and relate.

5. Walking in Japan

For A Straight Hundred Mile Walk in Japan, Long visited Japan for the first time in 1976. Since then, he has come to Japan frequently to walk. In 1984, Long confessed to difficulty when he walked through different landscapes:

I think it does take a long time to really become absorbed into different landscapes and to kind of understand them in a way which has some meaning. I think it’s something that I’ve hopefully learnt through experience to become at one in a different and new landscape and become absorbed by it and get into a state of mind where I feel very relaxed and that I’m not using it and I’m not making the work in the wrong way.[61]

Long’s works in Japan show how he has become absorbed in Japanese landscapes and how he made them in the “right way.”

In 1979, Long revisited Japan and created Stones in Japan[62] and A Line in Japan, Mount Fuji.[63] They were part of lines that Long made with stones in various places in the 1970s and 1980s, such as Iceland, Switzerland, Wales, Inishmore (Aran Islands, Ireland), and the Himalayas. In these works, Long “rearranged” the places with lines of stones that formed continuous lines or “meshwork” over the surface of the earth.

In the text work A Moved Line in Japan (1983),[64] Long carries an object to exchange with another object, then does the same again and again on a 35-mile walk along the ocean. Long picks up a shell and carries it to exchange for a crab. Then, he exchanges the crab for a feather, and so on. This work is one of the earliest in which Long carries found objects other than stones. Unfamiliar or otherwise appealing materials required Long to carry them and walk; that is, they required his body as a medium. As a walking medium, he felt his physical reality. In this walk, Long found that the materials let him walk. Through the agency of unfamiliar materials and a means of exchanging them along the walk, Long tried to be absorbed into a particular place of the Japanese landscape.

In 1992, Long visited the Ryōanji Temple in Kyoto and, after looking at a particular rock in the rock garden, he began an eleven-day walk in the mountains to the north of Kyoto. This walk produced the text works Mind Rock, Japan Winter,[65] and Along the Way: An Eleven Day Walk in the Mountains North of Kyoto, Japan Winter.[66] In the latter, below a photograph of snowy traces of his walk, Long mentions the things he had encountered in the walk: the cawing of crows, a silver-painted stick, a gold Buddha, a glass of sake, a bowl of rice, a kingfisher, gusts of warm air, the smile of an old woman, and so on. That Long had never mentioned his meeting with people in the text works he made on Dartmoor discloses that his relationship with the Kyoto landscape became more humanly intimate. Donald Kuspit argues that the smile signifies the acceptance of the other as a form of interrelationship in contrast to the cry that yells out one’s own social isolation, as seen in the figures of Francis Bacon’s paintings.[67] The smile of an old woman that Long receives emphasizes his intimate relation to the Japanese landscape in which the unfamiliar is familiarized.

Five years later, in the summer of 1997, he walked the Shirakami Mountains in Aomori and produced a photograph and a text work, A Walk in a Green Forest, Eight Days Walking in the Shirakami Mountains, Aomori Japan (1997).[68] In the text work, he mentioned his actions in addition to the things he saw and touched during his walk. His recorded actions are, “WATCHING MOONLIGHT TURNING INTO DAWN,” “SITTING ON A MOUNTAINTOP AMID BEECHES AND BAMBOO,” “SLEEPING BY THE SOUND OF A RIVER AND A WATERFALL,” “BREAKING A CAMP AND BREAKING A CIRCLE,” and “WINDLESS WALK.” These actions in his continuous walk in the forest confirm his physical reality. In his engaging with it, the place becomes the in-between places, a medium, a threshold. The forest itself encompasses the in-between places. Long’s actions embed his body as one of the materials of the forest. An accompanied photograph to the text work shows his small and humble tent almost buried in shrubs and trees, beside a river. (Other photographs show his tent is green.)[69] Sleeping and doing some actions mentioned above in or beside this tent, Long inhabited the forest for a short time. In Kyoto, Long and the place were intimately “related” to each other and in the relationship. In the forest of Aomori, however, Long became part of the forest, or rather he is being the forest, the in-between places, like tadpoles and lilac.

In the back of the photograph is a circle that is independently taken in the photograph called Early Summer Circle, Aomori. In the forest, Long made two other circles for Shirakami Circle and Camp Stones, Aomori.[70] For Early Summer Circle and Shirakami Circle, Long removed the snow in a shape of a circle on the snowy ground. The black-and-white photograph of Early Summer Circle was taken from far above, as if he had taken it from the sky. Perhaps from the forest, Long took the black-and-white photograph of Shirakami Circle, capturing a circle and the snowy surface of the vacant plot in the forest. The photograph of Camp Stones focuses on the stone circle, his small green tent beside it, and the forest, zooming in the stony surface of the ground. These circles are marks of his inhabitation in the forest, or of his being in between the earth and the sky. Later, such circles are to be media to approach the cosmos from the earth; as Long confesses in an interview published in 2017, “The archetype of the circle emphasises the cosmic variety of everything and this gives it its power, beauty, understandability and resonance.”[71]

6. Transference between Dartmoor and Chōkai Mountain

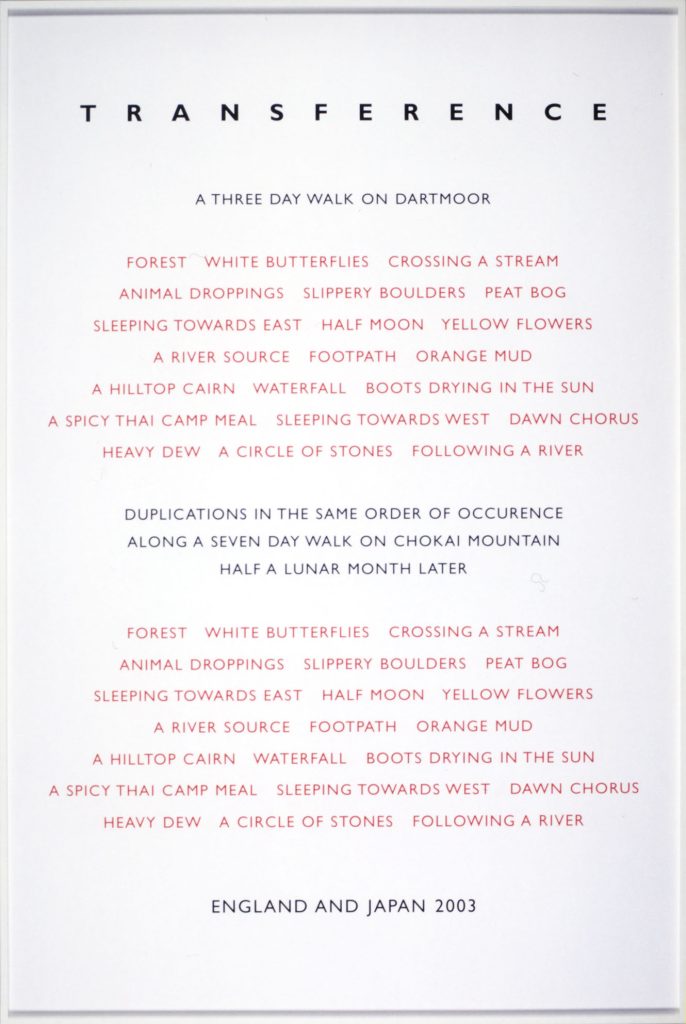

On July 20, 2003, Long started a seven-day walk on Chōkai Mountain, in the Tohoku region in Japan. From this walk, Long produced three works: An Exchange: A Hundred and Eight Stones from Each Cairn Placed upon the Other along a Seven Day Walk on Chokai Mountain, Honshu Japan, A Seven Day Walk on Chokai Mountain, Honshu Japan,[72] and Transference, England and Japan (2003) (Fig. 4)[73] For Transference, Long repeated a three-day walk on Dartmoor in a seven-day walk on Chōkai Mountain in a symmetrical form. His early pursuit of “the relationship between all things” led to an interest in the symmetrical relationships of the particles in the subatomic world. He talked about this text work to Craig-Martin in 2008:

It was based on a phenomenon in subatomic physics whereby a particle can act on the behaviour of another particle so as to create a symmetry of itself, over a relatively vast distance. I first made a walk on Dartmoor recording various things, and then later on a completely different walk in Japan, I deliberately looked out for and could find certain things that were the same as on Dartmoor, or did repeat, or I could make them repeat, even in the same order of occurrence. So it’s about a symmetry of places, or events, on different sides of the world, and universal phenomena.[74]

Forever Museum of Contemporary Art, Akita, Japan

©️ Richard Long. All rights reserved, DACS & JASPAR 2024 G3452

All particles interact under the rules of the symmetry of space and time. Physicists have argued that space-time symmetries, known in Erwin Schrödinger’s phrase as ‘quantum entanglement,’ are relevant to interactions of particles: “In general, symmetries place powerful restrictions on the nature of interactions between elementary particles.”[75]

Inspired by this phenomenon of particle physics in the subatomic world, where, Long said, “particles are in a flux of changing relationships between speed, mass, positions and time,”[76] he engaged with exchanging stones and produced text works such as The Same Thing at a Different Time at a Different Place, Winter (1997)[77] and An Exchange of Stones at a Place for a Time on Dartmoor, England (1997).[78] In the latter, Long exchanged a stone he found on Saddle Tor for a stone he had brought from Tierra del Fuego while on a three-day walk on Dartmoor. Long’s walking body and stones are media of the exchange of times and places. Even if Long did not make a sculpture, a stone was left to mark somewhere in the “in between” of Dartmoor and Tierra del Fuego.[79]

In a seven-day walk on Chōkai Mountain in 2003, Long exchanged 108 stones between the two symmetrical cairns, as if he were casting away the 108 vices or afflictions, recognized in Buddhism, and produced An Exchange: A Hundred and Eight Stones from Each Cairn Placed upon the Other along a Seven Day Walk on Chokai Mountain, Honshu Japan. The exchange was a kind of ritual of purification. In the ritual and the in-between cairns, the body’s action of exchanging stones takes on a spiritual meaning. The visible then encompasses the invisible.

Exchanging the stones led to exchanging the walks on Dartmoor and Chōkai Mountain. Long recorded those two walks in the text work Transference. In the work, Long’s body, as if it was then a particle, interacts with other things, such as white butterflies, animal droppings, slippery boulders, peat bogs, the half moon, yellow flowers, a river source, a footpath, orange mud, a hilltop cairn, a waterfall, a spicy Thai camp meal, the dawn chorus, heavy dew, and a circle of stones. In the vast distance over Dartmoor and Chōkai Mountain, these things and Long’s actions correspond symmetrically, like particles. The betweenness of the places now takes the form of symmetry. Long made the symmetrical walk on the places visible with words, but at the same time, the text work contains the invisible. The words remain, but the things, actions, and walks do not leave visible traces.

Long is strongly conscious of the continuous geological movement of the world. He states, “Nothing in the landscape is fixed; nothing has its ‘eternal’ place.”[80] Walking is an action to demonstrate that we human beings are part of this continuum. His sculptures are momentarily still, but in another moment the stones move somewhere else. Long’s knowledge of the continuous movement of the world led him to think of another level of continuation of the subatomic world, where particles are in a flux of changing relationships between speed, mass, position, and time. In this art, a human being becomes paired with a complementary “particle.” Like stones, we are always somewhere else in a relationship with others, thereby leaving traces of lines in the in betweens.

According to Han, nowadays, in the age of discontinuous events and times, “Our perception becomes sensitized to non-causal relations” and the narrative linearity ends. Consequently, “[a]esthetic tension is not created by a narrative development, but by the superimposition and compression of events.”[81] Against fragmented space and time, Long walks and marks impermanent traces as his art, thereby generating a poem or song in the place to stir the imagination of the viewers of his works and relating a narrative in the in-between places. This narrative, however, is not oral and discursive, but rather overtly physical. Long makes his sculpture as a trace somewhere in the in-between places and times and earth and sky along his way. The trace is impermanent and imperfect in the sense that it is never complete, and it therefore leads us incessantly to somewhere to somewhere else. Richard Long writes to Peter Cheyne in his personal correspondence of June 21, 2018, that “deep down, I am an imperfectionist.”[82]

Eriko Yamaguchi

yamaguchi.eriko.gm@u.tsukuba.ac.jp

Eriko Yamaguchi is a Professor of British art history at the University of Tsukuba, Japan. She has published various articles on nineteenth- and twentieth-century British art.

Published October 6, 2024.

Cite this article: Eriko Yamaguchi, “In-Between Places: Richard Long’s Walk-Works on Dartmoor and in Japan,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Volume 22 (2024), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] Richard Long, “Notes on paths,” in Stones, Clouds, Miles: A Richard Long Reader, ed. Clarrie Wallis (London: Ridinghouse, 2017), 303.

[2] Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History (London: Routledge, 2007), 81, 84.

[3] Tim Ingold, The Life of Lines (London: Routledge, 2015), 133.

[4] Ingold, Lines: A Brief History, 81, 84.

[5] Ibid., 80. Tim Ingold, “Looking for Lines in Nature,” EarthLines, 3, November 2012, 49. Henri Lefevre, The Production of Spaces, trans. D. Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 118.

[6] Ingold, “Looking for Lines in Nature,” 49.

[7] “Interview with Martina Giezen” (1985-1986), Selected Statements & Interviews, ed. Ben Tufnell (Manchester: Haunch of Venison, 2007), 86. Eriko Yamaguchi, “Ashi no Ato, Te no Ato, Iki no Ato: Richard Long no Chokoku niokeru Shosan” [“Footprints, Handprints, and Trace of Breath: Disappearance of the Sculpture of Richard Long”] (in Japanese), Forms of the Everyday: Art, Architecture , Literature, Cuisine, ed. Eriko Yamaguchi and Michiko Tsushima (Tsukuba: University of Tsukuba Press, 2023), 99-100.

[8] https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/item/a-walk-in-normandy/1003123 (accessed February 3, 2024).

[9] Byung-Chul Han, The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering, trans. Daniel Steuer (Cambridge: Polity, 2017), 37.

[10] Ibid., 37.

[11] Ibid., 36, 37, and 39.

[12] http://www.richardlong.org/Sculptures/2011sculptures/linewalking.html (accessed July 15, 2021).

[13] R. H. Fuchs, Richard Long (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1986), 46.

[14] Richard Long, “Royal West of England Academy” (2000), in Selected Statements & Interviews, ed. Ben Tufnell, 39.

[15] Richard Long, “Five, six, pick up sticks/ Seven, eight, lay them straight” (1989), Selected Statements & Interviews, ed. Ben Tufnell, 21.

[16] “Interview with Martina Giezen,” Selected Statements & Interviews, ed. Ben Tufnell, 70.

[17] Richard Long, “Words After The Fact” (1982), Selected Statements & Interviews, ed.Tufnell, 26.

[18] Long, “Five, six, pick up sticks,” 19.

[19] Wallis, ed., Stones, Clouds, Miles, 320-21.

[20] Long, “Words After The Fact,” 26.

[21] Wallis, ed., Stones, Clouds, Miles, 308.

[22] Fuchs, 45.

[23] Ibid., 45.

[24] “Interview with Martina Giezen,” 72.

[25] http://www.richardlong.org/Textworks/2011textworks/49.html (accessed July 15, 2023).

[26] Long, “Five, six, pick up sticks,” 15.

[27] Paul Moorhouse, “The Intricacy of the Skein, the Complexity of the Web: Richard Long’s Art,” in Richard Long: A Moving World, ed. Susan Daniel-McElroy, Andrew Dalton, and Peter Evans, exhibition catalogue (St Ives: Tate St Ives, 2002), 13.

[28] Long, “Words After The Fact,” 26.

[29] Ben Jacks, “Walking and Reading in Landscape,” Landscape Journal, 26, no. 2 (2007): 279. John Dewy, Art as Experience (New York: Capricorn Books, 1959).

[30] Wallis, ed., Stones, Clouds, Miles, 313. Richard Long: In Conversation, Parts 1 & 2 (Noordwijk: MW Press, 1985-86), Part 2, 14; qtd. in William Malpas, The Art of Richard Long: Complete Works (Maidstone: Crescent Moon, 2005), 340. G. Greig, “Circular Tours in the Name of Art,” Sunday Times, June 16, 1991; qtd. in Malpas, 339.

[31] https://www.moma.org/collection/works/147076 (accessed July 15, 2023).

[32] http://www.richardlong.org/Textworks/2011textworks/40.html (accessed May 5, 2023).

[33] Reproduced in Fuchs, 110, and Clarrie Wallis, ed., Richard Long: Heaven and Earth, exhibition catalogue (London: Tate Publishing, 2009), 84-85.

[34] Long, “Five, six, pick up sticks,” 18.

[35] Ibid., 17.

[36] Richard Long, “Abbot Hall Art Gallery” (1985), in Selected Statements & Interviews, ed. Ben Tufnell, 29.

[37] Long, “Five, six, pick up sticks,” 15.

[38] Clarrie Wallis, “Making Tracks” in Wallis, ed., Richard Long: Heaven and Earth, 59.

[39] Ibid., 47.

[40] “Interview with Yuko Hasegawa” (1995), in Selected Statements & Interviews, ed. Ben Tufnell, 106.

[41] Letter from Long to Clarrie Wallis, dated 1 September, 2008, qtd. in Wallis, “Making Tracks,” 47.

[42] https://www.artimage.org.uk/4694/richard-long/a-straight-northward-walk-across-dartmoor–1979-2010 (accessed February 3, 2024).

[43] Long, “Words After The Fact,” 25.

[44] Long, “Five, six, pick up sticks,” 17.

[45] Fuchs, 46-47.

[46] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/long-a-hundred-mile-walk-t01720 (accessed 5 May, 2023).

[47] https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/media/collection_images/Alpha/L2010.149%23%23S.jpg (accessed May 5, 2023).

[48] http://www.richardlong.org/Sculptures/2011sculpupgrades/plains.html (accessed May 5, 2023).

[49] http://www.richardlong.org/Sculptures/2011sculptures/honshuwalk.html (accessed July 15, 2023).

[50] Wallis, ed., Stones, Clouds, Miles, 320.

[51] Ingold, The Life of Line, 62.

[52] Ibid., 43, 45. Tim Ingold, “Earth, Sky, Wind, and Weather,” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 13 (2007): S33.

[53] Ingold, Lines: A Brief History, 79-80.

[54] http://www.richardlong.org/Textworks/2012textworks/anywhere.html (accessed July 15, 2023).

[55] Christopher Tilley (with assistance of Wayne Bennett), Body and Image: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology 2 (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2008), 267.

[56] Ibid., 269. I discuss this passage from Tilley in my “Chihyô no Arrangement: Richard Long ga oru Fûkei” [“Arrangement of the Earth: Landscapes Woven by Richard Long”] (in Japanese), Journal of Modern Languages & Cultures (University of Tsukuba), 11 (2013), 21-23. This paper presents the early stage of my research on Long discussed in the present article.

[57] Tilley (2008), 268.

[58] Ibid., 271.

[59] “Interview with Martina Giezen,” 71.

[60] “Some notes on the work of Richard Long by Michael Compton.” British Pavilion XXXVII Venice Biennale, 1976.

[61] “Interview with William Furlong” (1984), in Selected Statements & Interviews, ed. Ben Tufnell, 62.

[62] Reproduced in Fuchs, 78.

[63] http://www.richardlong.org/Sculptures/2011sculpupgrades/japanline.html (accessed May 5, 2023).

[64] https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/L2010.60/ (accessed July 15, 2023).

[65] http://www.richardlong.org/Textworks/2011textworks/32.html (accessed July 15, 2023).

[66] https://www.jamescohan.com/exhibitions/roxy-paine-richard-long-magnus-wallin/selected-works?view=slider#6 (accessed July 15, 2023).

[67] Donald Kuspit, “Francis Bacon: the Authority of Flesh,” Artforum,13, no.10 (1975): 56.

[68] http://www.richardlong.org/Textworks/2011textworks/47.html (accessed July 15, 2023)

[69] Reproduced in Richard Long: Mirage (London: Phaidon, 1998, 2003).

[70] Reproduced in Long, Moorhouse, and Hooker, 118 & 121, and Richard Long: Mirage.

[71] “Richard Long Interview by Ina Cole,” Earth Sky: Richard Long at Houghton (Houghton Hall in association with Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2017), 34.

[72] http://www.richardlong.org/Sculptures/2011sculpupgrades/chokai.html (accessed July 15, 2023).

[73] On July 27, 2003, after a seven-day walk on Chōkai Mountain, Long made a mud work, Akita Waterfall Line: Sophie Junkei-kai Medical Institution, Akita Japan 2003.

[74] “And So Here We Are: A Conversation with Michael Craig-Martin, November 2008,” Wallis, ed., Richard Long: Heaven and Earth,175.

[75] E. Schrödinger, “Discussion of Probability Relations Between Separated Systems,” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, (1935) 31: 555-563: 555. I am most grateful to an anonymous reviewer for informing me of Schrödinger’s discussion of quantum theory. Committee on Elementary-Particle Physics, Board on Physics and Astronomy, Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications, National Research Council, Elementary-Particle Physics: Revealing the Secrets of Energy and Matter (Washington, D. C.: National Academy Press, 1998), 36. The italics are in the original.

[76] Wallis, ed., Stones, Clouds, Miles, 305, 307. I hereby express my gratitude to an anonymous referee for informing me of’ Erwin Schrödinger’s discussion of “quantum entanglement” and his article.

[77] Reproduced in Richard Long, Paul Moorhouse, and Denise Hooker, Richard Long: Walking the Line (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002), 54.

[78] Ibid., 56.

[79] I have discussed Long’s engagement with exchanging stones, citing the works of The Same Thing at a Different Time at a Different Place, Winter (1997), An Exchange of Stones at a Place for a Time on Dartmoor, England (1997), and An Exchange: A Hundred and Eight Stones from Each Cairn Placed upon the Other along a Seven Day Walk on Chokai Mountain, Honshu Japan, in my article of “Richard Long: Touching Stones with Stones, Touching Landscapes through Stones” published in Kritikos (forthcoming).

[80] Wallis, ed., Richard Long: Heaven and Earth, 147.

[81] Han, 40.

[82] I am most grateful to Professor Peter Cheyne of Shimane University, Japan, for sharing these words of Richard Long with me. My warm thanks to him for his continuous encouragement.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the editor and anonymous referees of this journal for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions. Thanks to their encouragements, I could keep walking, following Richard Long’s footsteps, and writing on his walk-works. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP19K00143, JP19K00149.