The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

Aesthetic Evaluation of the Atmosphere in Everyday Environments — A Case Study in Ashiyahama Seaside Town, Japan

Mao Matsuyama, Jaeyoung Heo, and Megumi Kawamura

Abstract

Since the emergence of environmental aesthetics, this field has been expanding its focus into various objects and environments including human-made objects. But still, it seems that we prefer aesthetically good environments and experiences because the word ‘aesthetic’ often automatically implicates some kind of positive value. However, as Timothy Morton suggests with the concept of dark ecology, we have to find a way to love “the disgusting, inert, and meaningless” that we have created and rely on as well, instead of dreaming a romantic and idealized world.

In this interdisciplinary research with aesthetics and environmental science, we will investigate the aesthetic value of the atmosphere in our everyday environments, especially the areas that have developed during the high economic growth period between the 1960s and 1980s in Japan. Such artificial suburban areas, in general, have been given aesthetically negative evaluations because of the lack of diverse natural conditions and human historicity. However, what, why, and how have not yet been elaborated enough. From this perspective, we carried out fieldwork using the “caption evaluation method.” By collecting hundreds of pieces of data from the participants, we aim to figure out how people perceive the various factors in the environment and experience, not a mere visual landscape, but the whole atmosphere.

Key Words

Human-made environment; atmosphere of suburban environment; caption evaluation method

1. Introduction

In the fields of environmental and everyday aesthetics, the importance of the human-made environment has gradually been noted. For example, in The Aesthetics of Human Environments,[1] which followed The Aesthetics of Natural Environments,[2] Arnold Berleant and Allen Carlson argue that “we may have an intuitive sense of a natural environment…yet environmental research has made it clear that we are unlikely to find any place that has not been affected by human agency.”[3] They continue, “These include not only the landscapes and countrysides that have been shaped by centuries of human habitation and utilization but also those that have resulted from more deliberate planning and design.”[4] In fact, given that most people living today spend most of their time in artificially created environments, rather than in wild nature, it was inevitable that the environment to be treated by aesthetics expanded and diversified to include them. Moreover, as Timothy Morton put it, beyond merely shedding light on the artificial environment, “the most ethical act is to love the other precisely in their artificiality, rather than seeking to prove their naturalness and authenticity.”[5] As concrete examples of ”the other,” Morton mentioned Frankenstein and replicants that appeared in the film Blade Runner; but if we take the definition of intersubjectivity as broadly as possible, then not only artificial persons, that is, artifacts in human form, but also all the artifacts around us and the artificial environments as an accumulation of them, emerge as the others to be loved. In fact, thanks in part to the pioneering work of Berleant and Carlson mentioned above, the subject matter of environmental aesthetics has expanded beyond the quasi-natural, such as gardens and parks, to include cities, suburbs, shopping malls, and theme parks.

On the other hand, while the subjects of aesthetics have expanded, the narrator of aesthetic experience has been limited to a small and narrow group of professional authors, due to the methods inherited from traditional aesthetics. This means that only persons familiar with the history and examples of aesthetic discourses and neighboring art fields—or those who can consciously or unconsciously use the aid of knowledge and theory, and who therefore perhaps have a markedly acute aesthetic sensitivity—have been the central narrators.

This is, of course, true of academic research in general. However, this limitation on who qualifies as a narrator of experience cannot be ignored, when the issue is not only objects with clear contours and volumes but also atmospheric elements in the environment around us and, more specifically, our everyday life.

Based on such awareness, this study attempts to clarify aspects of the aesthetic experience of nonspecialist subjects. It describes what they are conscious of and what they perceive in their everyday environment, by using what is referred to as the caption evaluation method. This method was originally devised and developed by Japanese researchers in the fields of environmental science and urban planning theory.

As will be explained in more detail in section 3, the caption evaluation method is a simple technique whereby unspecified participants walk around a particular environment, take photographs of objects or scenes that interest them, and freely describe in relatively short sentences what they perceive at that time.

Unlike questionnaire surveys in which participants select answers or options prepared by the survey operator, participants spontaneously describe their own experiences, including those from the stage of deciding what to focus on. This makes the caption evaluation method suitable for aesthetically oriented qualitative analysis. Simultaneously, it is a simpler method than long interviews with specific individuals, and it can collect from multiple subjects a certain amount of formal data that can be quantitatively analyzed to reveal the qualities of an environment with a certain degree of objectivity.

Although the overall research is still in its infancy, this paper explores how people perceive and evaluate their everyday human-made environment in relation to the atmosphere. The supporting fieldwork was conducted in a residential area in the Western region of Japan.

2. Considering a reclaimed land

In a personal conversation, Gernot Böhme once said that the first step to thinking about an environment, especially the atmosphere that fills it, is to begin by taking on the experience in the first-person and speaking about it phenomenologically. In his published work, he states the following:

The atmosphere is a perceptual object and is not to be had other than in actual perception. This fact might make the relation between atmosphere and the concept of atmosphere particularly precarious. …When I think of atmospheres or talk about atmospheres, I take a different I-standpoint relative to the atmosphere than in the perception of atmospheres. Because, in the perception of atmospheres, I am either myself dissolved into the atmosphere filled with a certain mood or I am still affected in distancing from it. When thinking about atmosphere, I go beyond these relations into another dimension of unaffectedness.[6]

There is indeed a big gap between experiencing the atmosphere and discussing the atmosphere. Nevertheless, we cannot talk about the atmosphere without a first-person experience of it, and we cannot give any concepts about the experience of the atmosphere without putting its experience into words. In this sense, the starting point is my own experience.

From the south-facing window of my house, I can see an open landscape. This is because my room is located on the fifth floor and there are no tall buildings in the vicinity to block my view. Except for the sky, the landscape is mostly composed of human-made structures or buildings. Trees can be seen in some places, but they too have been planted and cared for by humans. To the west is an eye-catching cluster of high-rise housing complexes. At night, when the windows are lit up and the red aviation lights flicker, the surroundings look like a scene from a sci-fi movie, even though there are no replicants and no “blade runner” chasing after them. In addition to the accumulation of these individual objects, even the ground on which they stand is actually “built.” In other words, the landscape that spreads out from my window is constructed on the artificial ground of reclaimed land.

In Japan, especially during the period of high economic growth from the 1960s to the 1970s, rapid residential land development took place mainly in the periphery of metropolitan areas such as Tokyo and Osaka. These were sometimes called “new towns,” and they became the sites of social structural changes that dismantled the old Japanese family system centered on rural villages and several generations living together. This led to a rapid increase in the number of nuclear families consisting of a father working in the city, a mother as a housewife, and their children.

Humphrey Carver’s Cities in the Suburbs, a pioneering work on suburbanism, discusses how a sense of community can be restored in the face of lamentation over the bleak suburbs.[7] In Japan, the topos of suburbs has been discussed from a sociological perspective since the 1990s, when the generation that was actually born and raised in the suburbs came to the forefront of the debate. In common with Carver’s discussion, the “pathology” of the suburbs has been depicted in terms of disconnection from traditional communities, domestic violence, delinquency among young people, relationships with roadside businesses, and mass consumption society. The emptiness, feelings of deprivation, and the anonymity of the suburbs have also been emphasized through artistic representations such as photographer Homma Takashi’s Tokyo Suburbia (1998), a collection of his works. While this image of the suburbs has been carried over to recent years, there have been discussions of overcoming the dichotomy between the suburbs and the ideal original landscape.[8] For example, Masatake Shinohara, known for his translation and introduction of the work of Timothy Morton, superimposes his own experience of visiting Senri New Town in Osaka upon Kobo Abe’s description in The Ruined Map. Shinohara writes as follows:

To perceive the city without a prepared axis, the human subject who tries to perceive the city must enter the city and try to think while perceiving the rhythm and motion of the city. This is to acknowledge and accept that one is part of the artificial city, and in the process, the human subject is dismantled into a pure voice, the word itself.[9]

I, myself, did not remain in the position of looking out of a fifth-floor window at the landscape of the reclaimed land. Benno Hinkes suggests the connective term “(gebaute) menschliche Umwelt” as a term that carries both meanings: the meaning of “human environment,” which emphasizes the realm of human life and activity, and of “built environment,” which directly indicates that it was built by humans.[10] This reclaimed land, though planned and built, is transformed into an existential living space for me, bringing a more complex atmospheric experience than just one of emptiness, feelings of deprivation, and anonymity.

Here, however, I would like not only to be the subject of my own voice but also to listen to the voices of other subjects. To this end, this study attempted fieldwork to verbalize the experiences of various subjects in the environment. It would become a case study of a plot of landmarked, sci-fi-like housing complexes in the area.

3. Case Study in Ashiyahama Seaside Town

Before going into the details of the fieldwork, I would like to briefly explain the origins of the reclaimed land and Ashiyahama Seaside Town.

Ashiya City is located between Osaka, the largest metropolis in western Japan, and Kobe which developed as an international trading port city and is therefore known as the “Hanshin-kan (between Osaka and Kobe) area.”

During the late Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods (ca. 1900-1930), the area was developed as a residential and holiday resort for wealthy people who had succeeded in business in Osaka and Kobe and for foreign residents. A lifestyle culture that later came to be regarded as “Hanshin-kan Modernism” flourished. In this way, housing development in the early stage was centered on the uptown and aimed for a kind of “Garden City.”[11] But as mentioned above, the population growth after World War II was much more drastic and residential areas began to develop in the direction of the seaside area facing Osaka Bay.

In Ashiya, reclaimed land in the waterfront area was also constructed during this period, with the completion of Ashiyahama Seaside Town in 1979. It was highly regarded for its eye-catching futuristic design that was unusual for a group of large-scale housing estates: uniform but different heights, an uneven layout, green zones, and canals built up around it. New towns such as this have often come under criticism for their artificiality, inorganic appearance, and the violent way they have emerged from the reclaiming of scenic beaches of white sand and green pines.

Haruki Murakami, who spent his youth in the area, wrote in his essay, “Walking to Kobe,” about his experience of visiting his hometown two years after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995.

Past the banks of the river, the area around what used to be the Koroen seaside resort had been filled in to make a kind of cozy little cove, or pond. Windsurfers were there, doing their best to catch the wind. Just to the west, on what was Ashiya beach, stands a row of high-rise apartment buildings, like so many blank monoliths.[12]

Even though this monologue of course contains Murakami’s very personal feelings towards his lost hometown (that was devastated by the unprecedented earthquake), the impression of a monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) can be understood as a common image for new towns developed around the same time in many parts of Japan.

This is one of the voices in the first person. However, there are also those, like me myself, who were born later than Murakami, or who regardless of age were unaware of the original beach that evokes nostalgia and came to live here after first encountering its current form. Some may have continued to live on the land throughout the development and the earthquake and have accepted the changes, while others may have visited the land by chance.

By considering these multiple perspectives, this study aims to open the door and to examine from an aesthetic standpoint the stereotypical images that have been given to suburbs and new towns in the discourse that has flourished since the 1990s.

4. Caption evaluation method

As a method, this study attempts to utilize what is called the “caption evaluation method.” This method was originally devised and developed by Takaaki Koga in the mid-1990s,[13] with reference to Masaaki Noda’s “Photo Projective Method”[14] and the “Evaluation Grid Method,” by Junichiro Sanui and Masao Inui.[15] It has been widely used as a method for collecting intuitive and empirical data from the general public.[16] The basic procedure, described in a paper published in 1999, is as follows:

(1) Survey participants walk freely through a certain course with a camera.

(2) If they find something interesting or meaningful, they photograph it and record its location on a map.

(3) They should give it an intuitive evaluation in three categories: positive as ○(+), negative as x(-), or unknown as ?!

(4) The photos should be captioned with the following information:

(a) Factor (of what)

(b) Characteristics (how it is, which part of it)

(c) Impression (what the participants think, how they feel)

(5) The participants repeat (1)-(4) as they like until the end of the course.

In this fieldwork, the participants used their own smartphone cameras for photography, and the data was collected via Google Forms. While all participants were uniformly tasked only with a walking route with a fixed starting and ending point, it was left to each individual to decide at what speed to walk the route, what to look for and how to evaluate it, what words to use for evaluation and description, and how many data items to collect. Therefore, it is possible to measure the participant’s evaluation process of actively finding elements worthy of attention, rather than forcing a passive evaluation of the elements that make up the environment, as in a questionnaire survey where the items to be asked about are prepared beforehand.

In general, sociological qualitative research aims to elucidate the psychological characteristics and origins of a specific group of people, such as factory workers or people belonging to a certain gender category, by clarifying the influence of the family and social environment over the medium to long term. In this case, long interviews with specific individuals and methods in which the researchers themselves enter the target group are suitable. On the other hand, in aesthetic research, which focuses on qualitative evaluation of a certain environment rather than delving into the background of the human subjects, the caption evaluation method, which can easily collect intuitive sensations and perceptions from a large number of subjects during a shorter time phase, is considered a suitable method.

Because the medium of data collection is photography, the participants’ interest is inevitably guided by visual objects. When walking around in the environment, sounds, smells, wind, and skin sensations are also active, but it is difficult to record these in their original form, at least in a technical sense. So this should be understood as a limitation of the method at present.[17]

However, participants were told that they could include nonvisual objects and elements, and the inclusion of free verbal descriptions and photographs meant, as we will see later, that some of the data collected referred to elements not visible in the photographs. At the same time, even though visual information and verbal expressions taken together are only one aspect of our experience in an environment, they are really dominant in our usual perception and cognition for better or for worse. Therefore, the data obtained from the caption evaluation method can be said to bring to light our somewhat natural experiences, including these perceptual and cognitive biases.

5. Results and Analysis

This section analyzes the results of fieldwork conducted in March 2023.

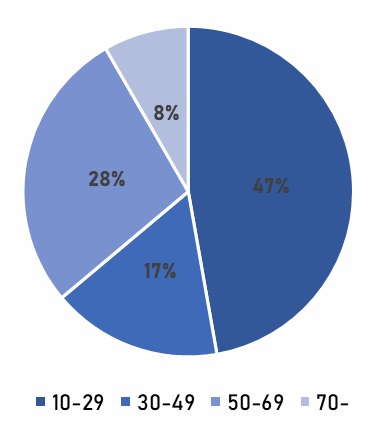

We assembled thirty-six participants from different generations (graph 1): 39% of them are resident in this area and 6 % are non-resident. The total number of the collected data was 283.

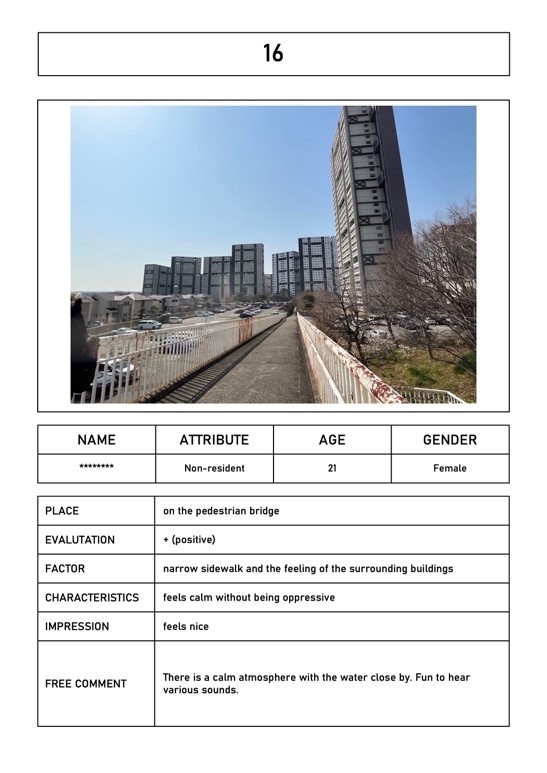

Each piece of data is carded in the following way to enable it to be classified. In practice, the following symbols were used: ○ for positive evaluations, × for negative evaluations and ?! for neither. In this paper, however, ○ is replaced by + and × by – for a more universal notation. The upper part of each card contains a photograph taken by one of the participants, and below that is data indicating the participant’s attributes. At the bottom of the card, the place where the participant took the data, the evaluation (+, -, ?!), and their own brief description of what (Factor), which part or details (Characteristics), and how they felt (Impression) (Figure 2).

Then, the 283 cases of data cards are to be classified using the KJ method, following the basic protocol presented by Koga. The KJ method, with an affinity diagram, is commonly used in qualitative surveys to organize an unspecified number of data points, creating minor and major categories. This simple way, which classifies keywords based on their natural relationships and similarities, was invented by the Japanese ethnographer Jiro Kawakita (1920-2009).[18] While this method allows qualitative data to be quantified to some extent, each analysis will produce fluctuations because categories and classification groups are generated by each analyst from words found in the data, rather than predetermined words. However, this fact does not indicate a weak point of the method, but rather can be understood as a strength for heuristic and creative interpretations of the meaning of data and relationships among data. In the field of environmental science, after categorizing keywords using the KJ method, the goal is generally to objectify the data as much as possible and to reduce or even cancel bias of the individual analyst as much as possible, using statistical processing such as the chi-square test and specialized applications. In this paper, however, data processing is limited to basic categorization and quantification, and we would rather focus, in an analog manner, on details that objectification tends discard. Therefore, the analysis will basically proceed in each section of “Factor,” “Characteristics,” and “Impression.” But in some cases, it will cross sections so that the real and complex experience of participants in the environment can be reconstructed.

5-1. Built environment vs. nature?

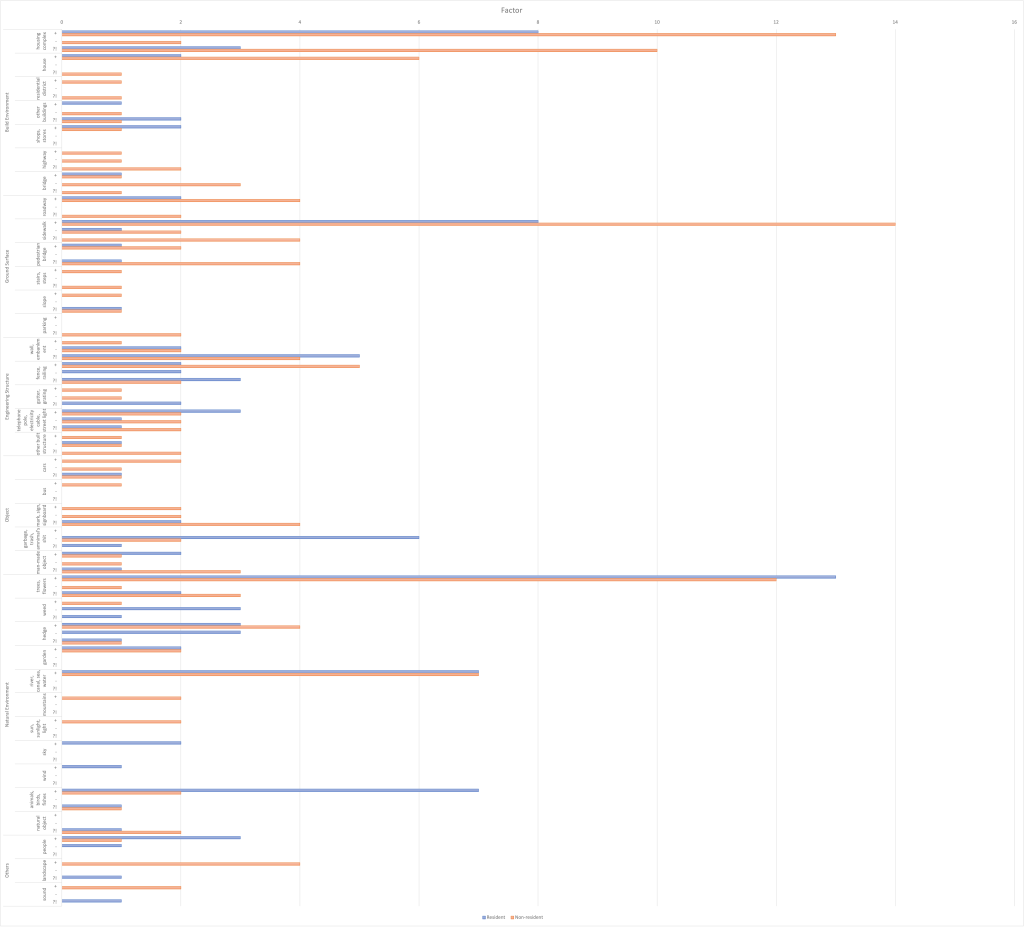

Let us look at the results of the analysis. First, looking at the “Factor” category, the most mentioned major categories here are “built environment” and “nature” both among the residents and the non-residents (Graph 2).

The category “housing complex” refers to the most eye-catching object in the area.[19] The housing complex has an inorganic and uniform design, but positive evaluations are noticeable. They vary from the color and design of the building itself to a focus on the arrangement of the multiple buildings and their relationship to other objects.

In the “Factor” category, alongside “built environment,” “nature” was most frequently mentioned. Overall, “trees and flowers” had the highest frequency of occurrence. Two other categories—“river, canal, sea, water,” which characterizes the waterfront area, and “animals, birds, fishes,” which includes the fish and turtles that live there—were also relatively high in frequency and generally given a positive evaluation. The results show that the mere existence of any natural object was itself a reason for positive acceptance, and this confirmed common sense and one of our empirical assumptions.

Interestingly, however, there was also an evaluation of the combination of two categories: “housing complex” and “nature.” The combination of “inorganic buildings contrasting with trees” (No. 98, Figure 3), “towering building against a blue sky” (No. 123) and “white flowers and buildings” (No. 197, Figure 4) are noted by some participants. In a complex and hybrid everyday environment, each element is not always perceived in isolation, nor is it appreciated as a cut-out scene, as in a landscape painting. This suggests a situation in which the perceivers are momentarily capturing a certain combination of elements as they change position through walking.

This may be related to the fact that in addition to “built environment” and “nature,” there were many references to “sidewalk” and “ground surface” (Figures 5 and 6). Many participants were paying attention to the form, view, and condition of the sidewalk that from moment to moment presented different points for attention as they walked along it, and turned their eyes to things and scenery in various directions and various distances. This result can be interpreted as in line with the argument made by Mami Aota in reference to Berleant’s aesthetics of engagement. She points out that the multilayered nature of aesthetic framing is not limited to indifferentism. It includes not only the “macro changes” of a certain environment formed by knowledge and historic stories, but also the “micro changes” that occur when the subject is actually active in a certain environment.[20] What is being produced here is not the universal wholeness of the environment, nor mere fragments, but a sequence of images that are generated and then successively replaced by others.

Furthermore, some of the participants who focused on the category “sidewalk” not only described the sidewalk’s objective characteristics but also linked their experience of it to the overall atmosphere of the place and to their own feelings. For example, in the response by No. 10, we see the description “sidewalk (Factor) / is making me feel spring atmosphere (Characteristics) / I feel like being guided by the sidewalk” and in No. 44, “sidewalk (Factor) / the end of it is far away (Characteristics) / Life is a long road and I feel tired.” These results seem to be consistent with the argument by Adam Andrzejewski and Mateuz Salwa who attempt to understand the atmosphere “as a relational feature of a site,” rather than as a third term filled between subject and object or as a terminological device defining a quasi-objective and a quasi-thing.[21]

5-2. Care and maintenance

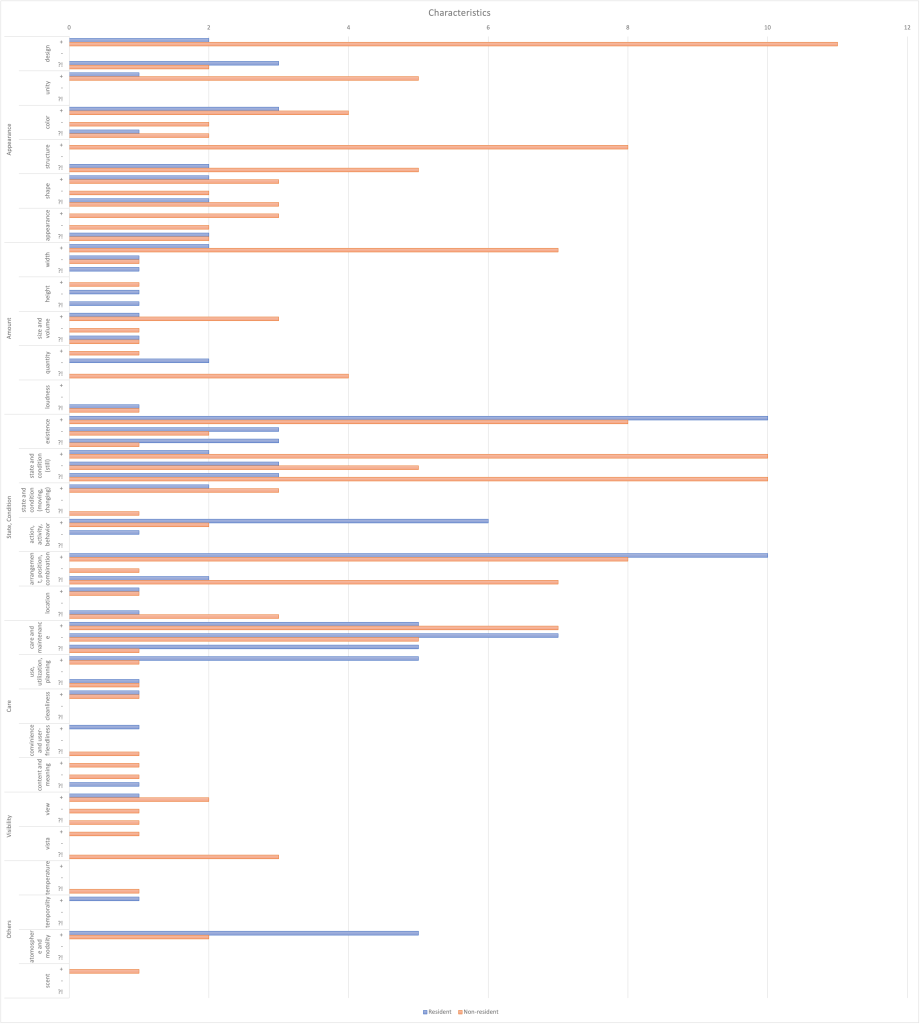

Next, we move on to the “Characteristics” section (Graph 3).

There are specific cases where the category “nature,” described earlier as tending to be positively evaluated for its existence, is negatively evaluated. This is when the degree of “care and maintenance” is judged to be inadequate.

For example, in No. 100, the “grass is overgrown,” in No. 122, the “vegetation is overgrown” (Figure 7), and in No. 217, the “weeds have grown” (Figure 8) are rated negatively. Similar evaluations are given to human-made objects. Rust on metal railings and fences (Nos. 11, 116, 192, 193, 194 (Figure 9), 196), dirt and messy painting on embankments (Nos. 153, 173, 250), and cracks in walls and on the ground (Nos. 139, 239) received in response such categories as “discomfort” and “dirty.”

On the other hand, in some cases, “care and maintenance” leads to positive evaluations. In the case of the pine trees in No. 64 (Figure 10), the tree in No. 177 (Figure 11), and the hedges in No. 181 (Figure 12), “maintenance” and “pruning” are the basis for the positive evaluation. These results indicate that even in the perception that occurs over a short period of time, people read not only the appearance of things, that is, their visually perceptible color and form, but also the degree to which they have been touched by human hands.

Similar evaluations were also found in the category “use, utilization, planning,” where the fact that footpaths are closed to cars and motorbikes (Nos. 125, 126, 147, 156) is particularly favorably received. These results overlap with the theory developed by Yuriko Saito under the concept “moral-aesthetic judgment.” That is: “such moral attribution is an aesthetic matter because our judgment is based upon the sensuous appearance of the object, unlike moral judgments of a person or an action that normally do not refer to the sensuous appearance of my body movement, the tone of my voice, and the like.”[22]

In her recent book, Aesthetics of Care, Saito also considers both interpersonal and person-object care relationships from the perspective of the “first-person.”[23] In the “care and maintenance” category, negative evaluations, often accompanied by questions and considerations, were more common among residents than nonresidents. In addition, seven out of nine references to garbage and trash on the street, classified under “state and condition,” were negative evaluations from residents. Although further research is needed to obtain statistically significant data, it is suggested that participants who are the very “first person” living in this area are more sensitive to the lack of care and maintenance. On the other hand, it is also important to note that even nonresidents who are only temporarily walking around the fieldwork area, as potential “first persons,” judge the degree of care and quality of the environment. Unlike the critique or appreciation of a work of art, the everyday environment arouses our interest in the existential and amateurish dimension of care.

As Martin Seel, in his book Eine Ästhetik der Natur, stated when he identified the second model of perception of natural beauty, we do not only appreciate the environment contemplatively, but also experience it relationally as the setting of our existential life.[24] In the data collected, albeit in statistically small insufficient cases again, more residents than nonresidents expressed specific concerns and expectations that the overgrown vegetation “puts me at risk of car vandalism because of the lack of visibility” (No. 122), or “looking forward to seeing the new shoots” (No. 177) of a neatly pruned tree. This shows a strong tendency not only to focus on the present but also to recall aspects of life that include a sense of temporality into the possible future.

5-3. Impression as perception of atmosphere

Having looked at “Factor” and “Characteristics,” which are relatively easy to categorize so far, we turn our attention to the “Impressions” section and realize that it is extremely difficult to summarize the great variety of expressions in a compact classification.

For example, in the “Factor” category, even if the word “building” is chosen by a participant, it can be summarized as “housing complex,” judging from the photograph and other descriptions. But in the “Impression” category, for example, “beautiful,” even if the word matches, there are as many nuances as there are data. In more complex expressions, there are many cases where the participants are trying to describe neither the attributes of the perceived object nor the sensations of the subject, but rather something atmospheric perceived at a site. In this category, therefore, we do not aim to forcibly unify the data, but to consider them from several perspectives. Besides, the descriptions in the optional field of “free comments” are also included.

As “Impressions” included expressions using the keywords “atmosphere”(雰囲気 [fun’iki]) and “mood” (気分 [kibun]), the following descriptions were noted: “calm atmosphere” (Nos. 16, 25, 30, 195), “everyday atmosphere” (No. 25), “comfortable atmosphere” (No. 67), “peaceful spring afternoon atmosphere” (No. 107), “steampunk atmosphere” (No. 212), “atmosphere of the river” (No. 213, Figure 13), “residents’ passage atmosphere”(No. 220), “refreshing mood” (No. 226), “heavy and dark atmosphere” (No. 240), “an atmosphere is emerging” (No. 249), and “the atmosphere soothed me” (No. 270).

The Japanese words “atmosphere” and “mood” have the flexibility to be associated with any adjective or noun. For example, the phrase “atmosphere of the river,” which accompanies a photograph of a bluish housing complex rather than the river itself, goes beyond simply stating the fact that “there is a river” or “I saw the river,” or describing the visual features of the building. The phrase is a way of relating the successive perceptions made by the perceiver as she walks around and attempts to expressively show the qualities of this whole environment.

In the case of “an atmosphere is emerging” or “the atmosphere soothed me,” the perceiver is not describing the nature of the perceived object but is sensing something floating in the whole place without being restricted to things. In addition, there is a more colloquial way of saying “感じ [kanji]” in Japanese, which softens the assertion or refers to something atmospheric. In English, it could be “feeling of …” or “sense of ….” For example, in No. 260, the participant states that “the color and shape” of a high-rise building seen in the distance “does not give me a good feeling,” showing an awareness of trying to express something like a subjective feeling, staying in front of a definitive evaluation of “not good” or “bad.”

Also, in No. 12 (Figure 14), it is stated that “the feeling of the pedestrian bridge’s / gentle slope leading to the building at the back / is exciting.” Here, the “feeling” can be understood as a feature attributed to the physical structure of the pedestrian bridge, which can be objectively described, but also as something already related to the perceiver’s mental state of being “excited.” Indeed, the category “Impression” contains many descriptions indicating such object-subject relational qualities, even without using such obvious keywords as “atmosphere,” “mood,” or “feeling.”

Expressions that mainly describe the objective state of the environment but which are linked to the mental state of the perceiver include, for example, “open” (Nos. 155, 159, 252) and “peaceful” (Nos. 118, 164). On the other hand, expressions that originate in the perception of the object but are more centered on the mental state of the perceiver include “comfort” (Nos. 10, 17, 57, 62, 149, 165) and “lonely, dreary, sorrow, sad” (Nos. 22, 42, 208, 40).

Also “exciting” (Nos. 12, 56, 61), “fun” (Nos. 29, 202, 203, 226, 253), “cheered up” (No. 69), “disappointed” (Nos. 124, 139), “uneasy, anxious, insecure” (Nos. 18, 67, 122, 158, 239, 272), “worry, concern” (Nos. 127, 246), and many other statements refer almost exclusively to the perceiver’s mental state. These can be called aesthetic reactions that go beyond aesthetic perception. Therefore, the aesthetic evaluation made at this moment is not a judgment of the goodness or badness of the objectified thing or landscape from a neutral observer’s point of view, but a reflective perception of the perceiver’s own condition.[25]

In architectural studies, where the caption evaluation method was originally established, impression evaluations have been categorized according to the factors and content of attention, with items such as “function and environment,” “harmony and beauty,” “urbanity,” “culture,” and so on. However, even in its earliest surveys, the category “atmosphere/feeling” has already been found,[26] and the amount of data on both positive and negative evaluations is outstandingly high in comparison with other categories. But such surveys are often conducted to gather information for more practical town planning and redevelopment, and subjective data categorized as “atmosphere/feeling” seems to have been rather difficult to handle.

Still, if the architectural practice is also ultimately aimed at the psychological well-being, or in other words, the happiness of the people who live in a certain environment, then these vague and even trivial expressions that capture atmospherics should not be neglected. There is still room for aesthetic approaches to make a contribution.

5-4. Design and aesthetic literacy

Böhme called the work of designers and architects ästhetische Arbeit because they are directly involved in shaping the environment and can therefore contribute to the creation and transformation of atmosphere. Indeed, in addition to the prominent landmark “housing complexes,” the fieldwork also included a number of references to the design of objects and the atmosphere they create.

Among them, the one thing that was often mentioned was the canal-side railings with designs of a seagull and a rower. All participants who drew attention to this gave positive evaluations of the design (Nos. 43, 72, 215, 224, 236, 247, 249, 267). Such designs are commonplace, especially in Japanese public spaces, and from a professional point of view, they are perhaps not particularly outstanding but rather somewhat childish in taste. If the sins of the new town, which was built by destroying the once beautiful nature of white sandy beaches and pine trees, can be offset by such a design, would Haruki Murakami condemn it as a terrible deception? Or would an aesthete with a background in public design and familiarity with examples from well-known designers dismiss a positive evaluation of such a banal, almost artistically worthless design as a lack of literacy on the side of the evaluator? Or, even if the design is mediocre, if the people who actually spend time there feel comfortable and begin to “love” the environment because of the design, is that the first step toward the true ethical act that Timothy Morton sought?[27] This paper is not in a position to make a hasty judgment between the sensibilities of those who see the fence as “fashionable,” “cute,” or “creating an atmosphere” and the perhaps more serious and sharpened sensibilities of the experts. At the very least, we cannot so easily dismiss the evaluations given by the fieldwork participants. Strictly speaking, it is not the evaluations themselves that we cannot dismiss, but rather the fact that people have come to terms with the design of the environment, even if it is not the best of the best and, on the contrary, have taken it as a positive.

6. Conclusion

In this research, focusing on one typical contemporary everyday environment, a suburban residential area, as a case study, we collected the words of ordinary people to approach their environmental experiences that could not have been revealed through expert narratives alone. This analysis is not absolute, and it will be necessary to discuss the results through comparison with statistical analysis from an engineering perspective and visual images created by text mining, for example.[28]

However, it is worth noting that the experiences of the participants were often consistent with the considerations and theories that have been developed in recent environmental and everyday aesthetics, and that, as we saw in section 5-1 and 5-4, unexpectedly positive attitudes toward human-made environments were also observed.

At the same time, there remains an unresolved difficulty in atmospheric studies. As already mentioned with reference to Böhme, this is the gulf that lies between the perception of atmosphere and the verbalization of atmosphere. Moreover, this gulf is sharpened through linguistic acts, including translation, just as in this paper. When a perceiver uses the word “感じ[kanji] = feeling of/sense of” to describe his/her atmospheric experience, the verbal phase has already left the phase of perception itself. However, this feeling would not be possible without the sensibility that has been cultivated in the cultural and living spheres where the word “感じ” is used, and in the back-and-forth between experience and language. Böhme distinguished between the concept of “dog” and the concept of “atmosphere,”[29] but if we include everyday words such as “感じ,” we can say that atmosphere is also something that can be perceived only because there is a word to describe it. In this sense, aesthetics, which has struggled to discuss the sensibility that cannot be verbalized, not by detecting or measuring it, but by somehow verbalizing and describing it with the language, can be said to be in the central realm of discussions about the atmosphere.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Urban Innovation KOBE Project (Project No. 22014, “A Case Study on the Aesthetic Qualities of Landscapes in Suburban Residential Areas of Kobe City: From the Viewpoint of Ordinary Citizens”). We would like to express our gratitude.

Mao Matsuyama

maoagamatsuyama@gmail.com

Mao Matsuyama is an associate professor at the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Design, Okayama Prefectural University. Her research focuses on the relationship between human beings and human-made things, from daily tools to the vast scenery of the urban environment. Her recent paper, “Aesthetic Range of Martin Seel’s Concept of Aesthetic Recognition” (written in Japanese), appeared in the Japanese Journal of Aesthetics (2020).

Matsuyama received her masters degree from Hokkaido University, where she studied natural science, aesthetics, and art theory. She worked as a curator for the Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art from 2011 to 2020 and as a research associate for Mukogawa Institute of Esthetics in Everyday-life (Mukogawa Women’s University) from 2020 to 2024. She is currently writing her doctoral dissertation at Kyoto University and has been a member of the Kobe Institute for Atmospheric Studies since 2022.

Jaeyoung Heo

heo@cc.nara-wu.ac.jp

Jaeyoung Heo is a lecturer at the Department of Residential Architecture and Environmental Science, Faculty of Human Life and Environment, Nara Women’s University. He has been working in the field of environmental psychology and physiology and has conducted many impression evaluations of indoor and outdoor visual, light, and sound environments and of signs in public spaces such as train stations, using the caption evaluation method. Recent papers include “Investigation of the Visual Environment of Railway Station Stairs Using Qualitative and Quantitative Evaluation Methods” (Energies, 2022) and “A Study on the Comparison of Impressions of Tourist Information Signs Focusing on the Differences between National Languages in Japanese Regional Cities” (Applied Sciences, 2022). Heo received his Ph. D. from the University of Tokyo, Department of Architecture. He worked there as a project researcher and at Shimane University as an assistant professor.

Megumi Kawamura

megumi.kawamura.520@gmail.com

Megumi Kawamura studied in Jaeyoung Heo’s Lab and graduated from Nara Women’s University in March 2024 (BA). She was studying visual environment evaluation, design and theory of landscape, and urban planning.

Published on December 10, 2024.

Cite this article: Mao Matsuyama, Jaeyoung Heo, Megumi Kawamura, “Aesthetic Evaluation of the Atmosphere in Everyday Environments-A Case Study in Ashiyahama Seaside Town, Japan,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 12 (2024), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] Arnold Berleant and Allen Carlson, The Aesthetics of Human Environment (Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2007).

[2] Arnold Berleant and Allen Carlson, The Aesthetics of Natural Environment (Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2004).

[3] Berleant and Carlson, Ibid., 13.

[4] Berleant and Carlson, Ibid., 13.

[5] Timothy Morton, Ecology without Nature. Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London: Harvard University Press, 2007), 195.

[6] Gernot Böhme, “Atmosphäre,” Καλλιστα: the journal of aesthetics and art theory (Kallista: Bigaku Geijutsuron Kenkyū, Department of Aesthetics, Tokyo University of the Arts), 3, 1996, 134-135, written in German with Japanese translation by Miyuki Abe in the same volume (1-17).

[7] Humphrey Carver, Cities in the Suburbs (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962).

[8] In the Western world as well, there is an active debate to overcome the stereotype that suburbs, once envisioned as dream residential places, have degenerated into a nightmare in the modern era [Paul J. Maginn and Katrin B. Anacker (ed.), Suburbia in the 21st Century. From Dreamscape to Nightmare? (New York: Routledge, 2022)]. This volume also includes case studies from Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Finland, and other countries. As with cities, suburbs differ from region to region in terms of the purpose of their establishment and the course of their subsequent development. Therefore, it is important to first conduct case studies on individual suburbs, even in order to put them into philosophical discussion.

[9] Masatake Shinohara, Living New Town. A Philosophy of Future Environment (Ikirareta New Town. Mirai-Kūkan no Tetsugaku) (Tokyo: Seidosha, 2015), 67, written in Japanese.

[10] Benno Hinkes, Aisthetik der (gebauten) menschlichen Umwelt. Grundlagen einer künstlisch-philosophischen Forschungspraxis (Belefeld: transcript, 2017), 121-123.

[11] According to Tamio Takemura, such housing developments were inspired by the philosophy of “Garden City Movement,” by Ebenezer Howard in England, but based on a different philosophy that concerned not only public urban planning but also voluntary community-making by the residents themselves. (Tamio Takemura, Rethinking Hanshin-kan Modernism (Hanshin-kan Modernism Saikou) (Tokyo: Sangensha, 2012), 15-80, written in Japanese.)

[12] Haruki Murakami, “A Walk to Kobe,” tranl. Philip Gabriel, in Granta, 124, 6 (2013), published online. (Original: “Kobe made Aruku,” in Henkyo, Kinkyo (Frontier, Neighborhood )(Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1998), referred to e-book.)

[13] Takaaki Koga et al., “Participatory Research of Townscape, using “Caption Evaluation Method”—Studies of the cognition and the evaluation of townscape, Part1—,” Journal of Architecture and Planning, 64, 517 (1999), 79-84, written in Japanese.

[14] Masaaki Noda, Bleached Children.Toward the Cities in Their Eyes (Hyōhaku-sareru Kodomo-tatchi) (Tokyo: Jōhō Center, 1988), written in Japanese.

[15] Junichiro Sanui and Masao Inui, “Extraction of Residential Environment Evaluation Structures Using Repertory Grid Development Technique—A Study on Residential Environment Evaluation Based on Cognitive Psychology—,” Journal of Architecture and Planning, 367(1986), 15-22, written in Japanese.

[16] After the establishment by Koga, the method has been continuously referred to in the fields of architectural environmental engineering and theories of urban planning. Recent examples include a study of tourist information signs in Japan [Kei Suzuki and Jaeyoung Heo, “A Study on the Comparison of Impressions of Tourist Information Signs Focusing on the Differences between National Languages in Japanese Regional Cities,” Applied Sciences, 12, 3 (2022), published online] and a study on staycation in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam [Duy Thinh Do et al. “Urban Staycation Attraction Factors: A Case Study of Hochi Mihn City,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 22 (2023), published online]. In the former, for example, it is shown that, in addition to “visibility” and “clarity,” “harmonicity” is also important for the viewer’s positive impression, whose main role is to convey information. However, it is thought that an aesthetic approach that treats data more qualitatively can compensate for the problem that the inner reality of “harmonicity” is discarded in statistical analysis in these areas.

[17] Koga himself has also pointed out this problem. But the “Photo Projection Method” that he refers to is mainly intended for children who are not yet ready to express themselves linguistically, and only allows them to take pictures and read their deeper psychology from the images. The caption evaluation method, on the other hand, has been improved by encouraging free and everyday verbal explanations, so that nonvisual elements are also captured.

[18] Jiro Kawakita, Heuristic Method: For Development of Creativity (Hassou-hou: Souzousei Kaihatsu no tameni) (Tokyo: Chüōkōron Shinsha, 1967), written in Japanese.

[19] An object that stands out due to its physical size or unusual appearance, which is the first thing many people notice before evaluating it, can be called a “landmark” of its environment in the sense defined by Kevin Lynch. This may be related to the fact that many of the participants who mentioned “housing complex” did so at the beginning or early stages of the walking process. [Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1960)].

[20] Mami Aota, Critique the Environment. The Development of Anglo-American Environmental Aesthetics (Kankyō wo Hihyou suru. Eibeikei Kankyōbigaku no Tenkai) (Yokohama: Shumpüsha, 2020), 167-202, written in Japanese.

[21] Adam Andrzejewski and Mateusz Salwa, “What is an Urban Atmosphere?” Contemporary Aesthetics, 0, Special Volume 8 (2020), published online.

[22] Yuriko Saito, Everyday Aesthetics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 210.

[23] Yuriko Saito, Aesthetics of Care. Practice in Everyday Life (New York: Bloomsbury, 2022).

[24] Martin Seel, Eine Ästhetik der Natur (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1991), 89-134.

[25] This can be understood along the lines of the mechanism of self-sensing in perception described by Böhme using the concept of “Betroffenheit” [Gernot Böhme, Aisthetik. Vorlesungen über Ästhetik als allgemeine Wahrnehmungslehre (München: Wilhelm Fink, 2001), 77-86].

[26] Koga et al., Ibid., 83.

[27] This issue is also discussed in my article comparing the aesthetics of care in Saito with the approval theories of Seel and Axel Honeth: Mao Matsuyama, “Intersections of Everyday Aesthetics and Recognition Theories——A Study on Yuriko Saito’s “Aesthetics of Repair (ing),” Forum DOUGUOLOGY: Study on Tools, 28 (2023), 45-55), written in Japanese.

[28] Similar to this study, the following is a more comprehensive study that collects qualitative data on the objects people pay attention to and the experiences they gain through the act of walking in a certain area of the city. It analyzes them quantitatively by converting them into numerical values, and presents them through maps, plots, and other imaging methods. Although the purpose of this study is to capture the changes of the modality of the city caused by walking, rather than to evaluate good or bad, it contains many suggestions that can be useful in atmospheric studies as well [Yusuke Kita, City Walking and Urban Modality: Considering the wholeness of spatial experience (Kyoto: Kyoto University Press, 2023), written in Japanese].

[29] Böhme, Ibid., 134-135.