The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

Preserving Meaning in an Age of Algorithms and AI

David L. Hildebrand

Abstract

New technologies not only surveil and collect data about us, they also change and alter the way we make or preserve meaning, including aesthetic meaning. Accordingly, the ways we consider, research, and educate aesthetics will have to adapt, at least insofar as it keeps a new range of technological dimensions in mind. To help imagine such dimensions, this paper examines the opportunities and challenges of technologies offering new ways of creating things while also nudging and “hypernudging” our actions. Such developments may initially seem trivial but they are changing our relationships with one another and with ourselves. After a brief, largely factual discussion of how technology is disrupting habits to extract data, some impact on decision-making autonomy is presented. Next, Albert Borgmann’s work is utilized to better understand how these new technologies fit his account of devices and so affect skills, practices, and meaning. Next, Dewey’s position is considered to see how contemporary technologies affect inquiry, memory, and art. Finally, there is brief consideration of the potential for technology to affect empathy, which also affects the foregoing aspects at a fundamental level. The essay concludes with a brief summary of the concerns presented.

Key Words

art; Borgmann; Dewey, empathy; generative AI; habit; inquiry; meaning; memory; technology

1. Introduction: New technologies, new questions, and preserving value

As generative artificial intelligence becomes more sophisticated and is applied to more tasks, the intensity of reaction towards it increases. Some herald it as a miracle, others as a disaster. Of course, a wide range of reaction is typical for early phases of a new technology. In part, this is because there is always a mixture of technophobes and technophiles in the population; in part, it’s because tools are often launched before they are mature—real world use and enlarged data sets, after all, are necessary for their maturation. Much of the public’s early confusion might be diagnosed as metaphysical, insofar as people are as uncertain of the new tools’ purposes as they are about what the tools actually are. Indeed, already the variety of implementations being experimented with is myriad.[1]

Such uncertainties are multiplied for generative AI because this kind of tool, unlike most others, has a distinctly new potential for autonomy—the ability to generate novel output as it takes in new data and even learns from its interactions. Because so much is in flux with AI right now, it seems like now is the worst time to philosophize about it. Not only are these tools’ natures still in formation, there is a fair amount of noise around their capacity to address present dangers and uncertainties. In other words, concomitant with our appraisal of new tools is the challenge of confronting the sometimes complex or vexing problems to which they would be relevant.

Still, there’s no time to waste; various AI implementations, regardless of how early they are in their stages of development, are making a lot of stuff—images, sounds, models, simulations, and (maybe) even “art.” There is the potential to make a lot more, soon, and perhaps even autonomously. Such developments raise questions pertinent for both the everyday appreciation of aesthetics and one connected with the theme of this special volume. How will the coming changes affect how we understand what aesthetics includes? How does the addition of new technological factors change the nature of what researchers and educators consider germane to aesthetics, academically considered?

This essay will address these considerations first by posing a basic question worth asking of any new tool: Does it help with whatever is thought to be the original problem, without creating other, new problems? On balance, does it provide new opportunities and benefits, or are there significant costs and disruptions that deserve scrutiny?

Many people do not question technology. But for anyone concerned with meaning and value, questions must be pressed because new tools always change our relationships with one another and with ourselves. They change our environment (physical and cultural) and our habits; they modify whether and how well we make life meaningful. Sometimes, change is barely noticed—while some things go unaffected, others change; implicit values may be forgotten or omitted, often invisibly. But over a relatively short period, change can be enormous—consider the smart phone and social media. Even those engaged in aesthetic research and education can underestimate these changes, not least because of the way these technologies become woven into the fabric of daily life: how we communicate, the design of our appliances, the speed of experience. Anticipating and contemplating the meaning of such changes is a critical contribution philosophy makes to social life.

Here, I assess the potential ways emerging technologies may be affecting habits and practices important to meaning making and preservation; such practices include those classifiably aesthetic though not limited to that category. In section 2, “Technology and habits,” a brief discussion of how technology can disrupt habits is followed by an account of how technologies can nudge, tune, and profile users, all the while extracting data for further uses. This section concludes with a brief discussion of nudging and hypernudging, especially because of their impact on decision-making autonomy. This largely factual section is relevant to some of the philosophical discussion about meaning to come.[2] In section 3, “Borgmann on devices, meaningful practices, and values,” I examine Albert Borgmann’s claim regarding how device technologies, of which AI is just one kind, can affect skills and practices in ways that affect meaning and value. In section 4, “Dewey on technology, inquiry, and art,” I use Dewey’s standpoint to consider several impacts contemporary technologies can have on inquiry and memory, both crucial to meaning-making, before offering two assessments regarding AI’s impact on aesthetics. In particular, I take up (a) art as a connection between artist and appreciator (or experiencer) and (b) art as a crucial mirror societies can use to critically and constructively examine themselves. Finally, section 5, “Technology and empathy,” briefly considers the potential impacts of technology upon empathy. Empathy is critical to many of the meaning-making factors discussed in sections 2 through 4 and a factor frequently overlooked by techno-scientific engineers and designers. While I cannot do justice to the empathy issue here, it must be mentioned. The essay concludes with a brief summary of the concerns presented.

One caveat before continuing: My title’s mention of “preserving meaning” does not intend to connote a conservative standpoint. I do not start with the assumption that one should preserve the status quo just because it is the status quo. Rather, my motivation is the value we place on our agency, our ability to determine for ourselves what to keep and what to destroy. I argue that the conditions needed to preserve meaning depend upon some modicum of freedom from present technologies’ subtle or invisible manipulations; we must be allotted time and space in which to experience living, including our ambivalences and indecisiveness, along with our leaps of positive creativity. This type of freedom—a latitude to discuss, ruminate, imagine next steps—must not be hurried or rushed along by algorithms, designs, techniques, or artificial temporal scarcity that press us to enter into new ways of life that do not reflect our values. The factors recounted below impinge, I suspect, on this kind of freedom, which is why I place them under scrutiny.

2. Technology and habits

Much of the time we live in habitual ways. Habits, as Roberta Dreon explains, “are already pervasive in human life at a pre-personal level: individuals acquire most of their habits from an already habitualized social environment, by being entrained and attuning their acts, feelings, and thoughts to already existing ways of doing things and interacting with one another.”[3] Moreover, as C.S. Peirce noted in “The Fixation of Belief,” we are not likely to break from habit unless there is an interruption to the pattern.[4] As we reflect about technologies considered to be disruptive to habits, it is necessary to consider not only the methods, techniques, processes, and parties affected but also about the aims and values at stake implicit in these elements. This kind of comprehensive assessment is de riguer, of course, for questions involving technologies in industry practices or biomedical fields—think of familiar examples such as cosmetic companies’ animal testing or biomedical research into cloning; in these obvious cases, both methods and values are indispensable to fully evaluate (and even permit) a practice. The circumstances under scrutiny here are somehow different. When it comes to smart phones and the vast array of algorithmic technologies filling our lives, it is harder to see why there are values and aims at stake that deserve equally close scrutiny. But there are. Thus, my goal is to ask, “Which values are being included or excluded in these experiments?” and also, “What changes to meaning, aesthetic experience, and value more generally are being put at stake?” Such inquiries may start with how a new technology sustains or changes our habits, but those answers must be fully tested by judging whether and how a new technology fits into life in a meaning-preserving way.

2.1 Technologies which nudge, tune, profile, and extract data

To begin, consider some facts relevant to the habits technology impacts. Take the smart phone. In 2011 and 2015, Sherry Turkle and others helped document some of the social changes initially introduced by smart phones.[5] She tracked changes in attention quality and quantity, increases in distraction, and impacts on family life, friendship, and even on creativity and the nature of solitude.[6] More recently, Shoshana Zuboff documented the algorithmic and data collection strategies behind the devices and the companies that make them; she also writes eloquently about some of their implications for social and economic life. Both authors lay bare ways in which these technologies extract information from users in order to build data-based profiles that ostensibly benefit us and assuredly profit them.

To elaborate, Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019) describes the “extraction architecture” that has been developed around us.[7] The basic goal is to extract information about us—what we do or buy, where we go, what we say, who we are with, and more. Extraction mechanisms are embedded in phones, smart appliances, health apps, learning thermostats, navigation and location trackers, and much more. What makes this internet of things “smart” is automation—so-called “AI,” which manages how devices interact with one another and with humans. It can even affect how we act, right down to our language—just think of grammar corrections, autocorrection, autocomplete, and more. Increasingly, the territorial ambitions of data extraction penetrate the psychological, as well. As Zuboff writes, “extraction operations” want psychological ‘depth,’ the “highly lucrative behavioral surplus [that] would be plumbed from the intimate patterns of the self. The supply operations are aimed at your personality, moods, and emotions, your lies and vulnerabilities.”[8] This is the reason for reaction buttons, such as the “like” button, in social media sites.[9] The goal of these varied extractions was (and is) to build profiles not just about user preferences but of entire personalities.

What Zuboff did not fully realize in her 2019 book was how important data extraction architectures would be for “large language models,” such as ChatGPT, which require vast amounts of data—words, pictures, sounds we have created—in order to improve and diversify its capacity to perform many human tasks. The technological stability as well as the climatological and human impact of LLM’s is fast becoming a major political and ethical question.[10]

2.2 Nudging, hypernudging, tuning, herding, manipulating

Before discussing the implications of these technologies on the preservation of meaning, it is necessary to examine a bit more about how they work. Frequently, computer-mediated interactions on websites, while we are reading and writing, have the ability to “tune” or “herd” our habits and, thus, our behavior. Remember, the goal for many of these companies is to predict human behavior as precisely as possible. Some companies realized predictability improves when behavior is manipulated. In an interview, Zuboff explained,

[T]hese platforms are a giant experimental laboratory. The predictions today are exponentially better than the predictions a decade ago or a decade before that. One has to consider the immense quantity of financial and intellectual capital being thrown at this challenge. Next, these computational prediction products are sold into a new kind of marketplace: business customers who want to know what consumers will do in the future. Just as we have markets that trade in pork belly futures or oil futures, these new markets trade in “human futures.” Such markets have very specific competitive dynamics. They compete on the basis of who has the best predictions—in other words, who can do the best job selling certainty. The competition to sell certainty reveals the key economic imperatives of this new logic….[I]f you’re going to have great predictions you need a lot of data (economies of scale), if you’re going to have great predictions you need varieties of data (economies of scope). Eventually surveillance capitalists discovered that the best source of predictive data is to actually intervene in people’s behaviour and shape it. This is what I call “economies of action.” It means that surveillance capital must commandeer the increasingly ubiquitous digital infrastructure that saturates our lives, in order to remotely influence, manipulate and modify our behaviour in the direction of its preferred commercial outcomes.[11]

Such “economies of action,” as Zuboff describes it, use “machine processes…configured to intervene in the state of play in the real world among real people and things.…They nudge, tune, heard, manipulate, and modify behavior in specific directions.”[12]

2.3 Algorithms and autonomy

A critical question about these manipulations, these nudgings, arises when they cross an ethical line. One such line is between nudging and domination. Philosophers such as John Danaher call attention to algorithmic nudging, parts of what he has coined ‘algocratic’ systems. Those systems are able to nudge users so significantly that the techniques are, he argues, tantamount to “subtle forms of manipulation.” When nudges come quickly and repetitively, Danaher argues, they should be called ‘hypernudging,’ that is, “a kind of behavior change technique that operates beneath the radar of conscious awareness and happens in a dynamic and highly personalized fashion.”[13]

As the word implies, hypernudging is different than the more familiar term, ‘nudging.’ Nudging works by carefully arranging a choice, one with a bias that is transparently obvious to users and ostensibly in their best interests. One common example is the food buffet designed to place the salad first and the desserts last; this helps eaters make healthier choices. Hypernudging is different. It is not transparent; it operates quickly in feedback loops to keep nudging the user, over and over again, and it often does not have the best interests of the user in mind. The design of hypernudging algorithms is also personalized, using profiles of individuals drawn from extracted data, for extra leverage. As Danaher explains, these “algocratic technologies bring nudging to an extreme. Instead of creating a one-size-fits-all choice architecture that is updated slowly…you can create a highly personalized choice architecture that learns and adapts to an individual user. This can make it much more difficult to identify and reject the nudges.”[14]

So, what is the effect of hypernudging on the autonomy of users? One overt concern is ethical: the effect of hypernudging on users’ autonomy. (This can occur, for example, when hypernudges operate with speed or complexity beyond the abilities of persons with cognitive impairments, preventing them from making informed choices.) Some researchers in disability studies argue that hypernudging can cross a line into manipulation or even domination. Why? Because when algorithms execute many small, fast, often invisible influences—again, often personalized—the result can be a significant change, or manipulation, of possible choices. Such hypernudges are, in fact, a kind of micro-domination because they have a cumulative impact on user’s lives. The seriousness of this is magnified because it is typical for people to use online tools for many other functions—and so the manipulation happens against a backdrop of data mining, surveillance, and prediction.[15]

Let us pause briefly to take stock of the claims made so far. I started with the general claim that contemporary technologies present challenges to our ability to preserve and determine meanings and values. Next, I briefly described some of the technologies at work—in particular, those which extract our data, surveil online activity, and even hypernudge us toward certain choices over other ones. One ethical risk to hypernudging, micro-domination, was briefly mentioned. With these points in mind, I will look more closely at how these technologies start to affect our ability to preserve and make meaning.

3. Borgmann on devices, meaningful practices, and values

In books like Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life and Holding on to Reality, Borgmann orients readers to the contemporary technological world with his notion of the “device paradigm.” As Borgmann explains it, we live in a world where we need various commodities—heat, light, food, transportation, music, and a thousand other things. Some tools, he notes, are so adept at providing commodities that they remove virtually all burden. A switch gives us light, a dial gives us heat, a remote changes our television channel, a compact disk gives us music, a phone conveys our physical location, and ChatGPT writes our letter or answers many of our questions. What is frequently forgotten, Borgmann writes, is that the way a device delivers commodities often “makes no demands on our skill, strength, or attention, and…is less demanding the less it makes its presence felt. In the progress of technology, the machinery of a device has therefore a tendency to become concealed or to shrink.”[16] Most of the time, we don’t know how devices work—how the silicon chips or machine language powering them function. Their workings are concealed. It is typical for people living within a “device paradigm” to not really care, either, as long as the commodity “has been rendered instantaneous, ubiquitous, safe, and easy.”[17] For those concerned with aesthetics, however, this concealment has paramount importance, insofar as how things are made (poiesis) is relevant to understanding both the causes of aesthetic experience and the roots of artistic creativity. Borgmann’s extensive discussions of music in Holding on to Reality give eloquent testimony to this.[18]

The point Borgmann stresses is that devices not only deliver commodities instantly but also replace the complex network of activities and patterned social relationships. The instantaneity of the commodity tends to obscure the disruption for most people (though not the ones whose activities or livelihoods are disrupted, of course). We also tend to forget how some of those previous activities—like building a fire, collectively making a meal, playing music together—involved habits and practices of sensibility, skill, and collaboration with others. Such practices can open individuals up to “wider horizons” and more expansive “cultural and natural dimensions of the world.” He calls these “focal things and practices.”[19]

Borgmann’s larger point is not that every technological change is destructive of value. Indeed, many newer technologies replaced forms of labor that were difficult and harmful. Rather, Borgmann wants to show how the character of contemporary life can incline us, attitudinally, toward devices so that we become forgetful of what is being replaced—the existing methods that connect people and shape their character. We become increasingly bad at seeing, as he puts it, that the “limitations of skill [made possible by devices] confine any one person’s primary engagement with the world to a small area.”[20] Now consider not making a fire or cooking a meal, but hypernudging, ChatGPT, or other generative technologies; these technologies represent perhaps the epitome of the concealing and disburdening power of technology. When a website uses one’s data profile to iteratively nudge them toward a choice, there is a profound disburdenment of the agent—we seem to just be getting what we want. Or consider having AI write an outline for an essay, sketch the outlines of a landscape, or solve a problem; again, a commodity is instantly provided—with the machinery underneath completely concealed. In these examples, devices in effect are converting processes of inquiry, including artistic inquiry, into commodities. Realistically, for many mental chores, this creates no problem—no one regrets the invention of the calculator except perhaps grade school teachers trying to teach addition. But inquiry more generally can be a profound and imaginative process, one that can uncover latent meaning as well as forge new meanings. Some of that meaning, as Roger Scruton has pointed out, is very hard to reproduce mechanically because it is conveying spiritual ideas like “belonging.”[21] The potential for technology to short-circuit such processes—be they epistemic or aesthetic—is acute and lamentable.

The challenge posed by ChatGPT and generative AI, then, is not that it will help solve certain practical problems more quickly, but that it will tend to disestablish habits of inquiry, including collaboration, that we very likely want to preserve. So, if Borgmann is right about the way new technologies tend to erase earlier ones, and these include ways of doing things that are creative, educative, and intellectual, then we do not have much time to illuminate the epistemic and moral values that are challenged by algorithmic technologies. They are progressing very quickly. Our ability to preserve and make meaning rely on mounting a strong critique, now.[22]

4. Dewey on technology, inquiry, and art

Let us turn to Dewey to understand a few more of the implications of algorithmic and AI technologies on meaning. There are four areas in which these technologies reveal their capacity to degrade meaning: inquiry, memory, artistic creation, and cultural criticism. As with the phenomena mentioned above, the implications illuminated by Dewey’s philosophy bear upon how academics might understand what aesthetic experience and artistic making has been—and could become.

4.1 Inquiry

Many people who know a bit about Dewey understand that there are different phases of his career. There is the “instrumentalist” Dewey, who worked out a theory of inquiry in the 1890s while in Chicago, and there is a later Dewey, in the 1920s and 30s, who turned more intentionally to theories of experience and aesthetic experience. What is overlooked by separating Dewey into different phases is the degree to which he expressed a continual concern with what we might call ‘the experience of inquiry,’ even during his instrumental period. This sounds like a rather pedantic historical fact, so let me tell you why it matters.

When Dewey schematizes inquiry, it is as a five-stage process. In its most skeletal form, it includes: 1. feeling—of an uncertain or indeterminate situation; 2. problem-formation—the locating and defining of “the” problem; 3. hypothesizing—the suggestion a possible solution; 4. reasoning—the review of meanings and implications raised by the hypothesized solution; and 5. experiment—actual testing of the hypothesis to see consequences and adjudging whether it can be accepted and implemented.

Notice that the first phase of inquiry is feeling. In many synopses of Dewey’s pattern of inquiry, the phase of feeling is overlooked or glossed over. This is a mistake. For consider the beginning of an inquiry: there is a feeling something is not right in an experience. That feeling is more than just a simple signal: it is thick, that is, there is a how to the way things feel when they are “not right.” This feeling helps motivate and orient inquiry at the start. For example, think of the way an unusual smell of “burning” feels. Compare that to the feeling when a door handle is stuck. Both feel wrong, but the quality of their feeling is different. The ability to have that feeling—to feel its quality, with intensity and even duration—is part of inquiry.[23] This is why a really indeterminate situation can make one feel quite lost; we are “baffled and arrested,” not knowing yet what to think. As Dewey puts it, our “ideas are floating, not anchored to any existence as its property,” and our “emotions…are equally loose and floating.”[24] Often, we just stay still while this is happening. Recall Alcibiades’ speech in Plato’s Symposium about Socrates thinking about a problem by standing in one place all day. Dewey would have said he was not just calculating, but feeling as well! The feeling of this phase of inquiry is ultimately informative because, Dewey states, as inquiry proceeds it becomes clear that this pervasive quality runs through it. In other words, this felt quality helps decide how to respond and then, as the qualitative background, helps guide inquiry as it moves ahead. It provides a felt awareness of how the problem should hang together.

The relevant point about the felt phase of inquiry is that this phase needs to be recognized, accepted, and treated as both epistemically and phenomenologically real, part of experience. When new technologies such as generative AI rush us past this phase, this habit and the feelings instrumental to inquiry are destroyed. Inquiry is thus deprived of basic steps necessary to discover new and truths and solutions.

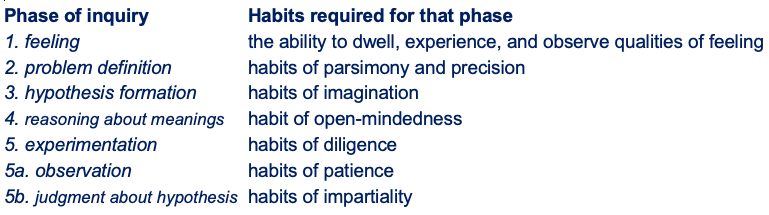

One can look more generally at inquiry, beyond the first “felt” phase to see other potential implications of new technologies. Consider the phases of inquiry just mentioned (elaborated slightly), along with the habits needed to make them effective:

Table 1. Inquiry phases and habits

These phases of inquiry each require various habits to be implemented effectively. As we turn more frequently to algorithms and AI to answer our questions, summarize our texts, and even create our art, music, essays, and letters, we “disburden,” as Borgmann would put it, our thinking using the AI tools, and in the process degrade the habits and lose the skills and cooperative efforts at every phase of inquiry. These habits have been integral to inquiry, including scientific inquiry, over countless years. They involve both partiality—engagement that involves our attention and interests—and impartiality, which requires that we manifest a kind of disinterest from the issues under investigation. Technological disburdenment, though, creates a new kind of disinterest, one critically different from that debated by academic aestheticians since Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment (1790). This disinterest puts the subject matter at such a remove from inquirers that all the tension normally a part of an act of disinterest is extirpated.

Thinking is messy; it is dialogical and involves struggles that are instructive. The promise of AI and algorithmic problem-solving is to save time, which seems an unalloyed positive. But in fact, AI will also tend to replace those activities in which we have to untangle our own thinking, argue with ourselves, pause and ruminate on meanings, and hopefully struggle to express what really matters to us. These are not mere mechanical, calculative steps; they are value laden. When we take time to do them patiently, they change us as we undergo them. If AI is permitted to substitute for inquiry to the degree that it changes what inquiry amounts to, there will be an incalculable loss of meaning.

4.2 Memory

Related to inquiry, and integral to it, is memory. In inquiry and otherwise, things and events are meaningful because we can make sense of what is present in light of past events. Given these facts, how is memory affected by contemporary technologies? Often, engagement with them involves quickly shifting from one content to another, by choice or by distraction, to pursue an amusing diversion or to satisfy an emotional need. In his day, Dewey observed life’s pace accelerating as the amount of information expanded. He expressed concern, especially to teachers, about the effects these phenomena were having upon experience and also upon memory. “Remembering,” Dewey wrote in 1902, “is…taking facts of our experience and putting them together to make a living organized whole….Genuine remembering involves control over our past experiences.”[25] Recall the successive phases of inquiry, above; each phase relies upon the control that memory provides—the ability to see present experience in light of past events and meanings. The danger of rapid distraction and quick switching is a degradation of our ability to carefully work through all the phases of inquiry.[26]

Let me mention one important caveat about memory. Scientific research about digital devices and memory is very young, and a burgeoning range of experiments are asking a variety of questions: Do smart phones cause us to remember less? Is digital amnesia a real phenomenon? Does social media cause depression? Does using GPS reduce grey matter density and increase the odds of dementia? And many more.[27] While scientists are nowhere close to consensus on any of these questions, we can state with more certainty that most of the new habits technologies are inculcating will be designed to prioritize companies’ objectives over habits critical to reflection and healthy remembering. There is still a significant lack of consultation or permission from the public, including educators.

Here, I’ll leave my commentary about inquiry, memory, and new technologies. It is worth stating, again, that some new tools will be innocuous and even really helpful; having AI find “the best flight between August and September for under $300 with a window seat” seems harmless and even attractive. But what is at stake here is not this or that inquiry; it is the way we habitually inquire. If we adopt technologies that denude inquiry of feeling, if we disburden ourselves too often by letting a machine problem solve for us, then we cede not just control of our method of inquiry to foreign agents but also the way we grow as we inquire—we lose what one might call the “bildung of inquiry”.

4.3 Art, technology, and meaning: the artist-appreciator connection

One final area to consider when relating technology and meaning involves art. Dewey called art “the greatest intellectual achievement in the history of humanity” because it could make manifest—selectively, imaginatively, on the conscious plane of meaning—the physical and biological roots of our being, the “sense, need, impulse and action characteristic of the live creature.”[28] “Aesthetic experience” is the result of organisms in transaction with one another and their environment. Such experience can sometimes be found around us, in “the events and scenes that hold the attentive eye and ear of man, arousing his interest and affording him enjoyment as he looks and listens.”[29]

Art and aesthetic experience are remarkable not just because they show connections between the physiological and the consciously meaningful but because they exhibit growth. He writes, “In a growing life the recovery [of unison with the environment] is never mere return to a prior state, for it is enriched by the state of disparity and resistance through which it has successfully passed.”[30] Such facts “reach to the roots of the esthetic in experience,” because when life not only survives but grows “there is an overcoming of factors of opposition and conflict…a transformation of them into…a higher powered and more significant life.”[31]

The connection with technology and meaning relies on understanding that art is no mere product, some object or event capable of stimulating a particular response or feeling; art is an organic connection between an artist who combines personal aesthetic experiences with (physical and symbolic) materials to create artworks that communicate some semblance of that experience to appreciators. Artists create artworks by “building up…an integral experience out of the interaction of organic and environmental conditions and energies….so that the outcome is an experience…enjoyed [by appreciators] because of its liberating and ordered properties.”[32] If one accepts just a few basic points made by Dewey’s aesthetics, the implications for AI are clear. That is, if one accepts (a) that aesthetic experience is rooted in embodied and emotional life, and (b) that artists use this for art-making, and finally (c) that art-making communicates with similarly embodied aspects of appreciators, then it is obvious that whatever patterns AI can replicate or generate will be no more than simulacra of experiencing and not experiencing itself. If art is more than just the stimulation of response—if it is communication that utilizes the artist’s ability to imaginatively transmogrify elements of experience sensed and felt and conceived—then art is categorically something AI cannot autonomously make.[33] While this claim may seem disputable, it seems almost self-evident that it raises questions that would become indispensable for academic researchers and educators to consider in their work.

4.4 Art, technology, and meaning: art as cultural criticism

The second aspect of art that bears upon technology and meaning-making regards art’s critical function. Art is especially adept at drawing attention, to re-framing, problems in social life. Such problems may be invisible or obscured by habits and ideological norms. Think of Willy Loman in Miller’s Death of a Salesman: “Attention must be paid!” The power of utopian and dystopian fiction’s possible worlds is rooted in connections to what is meaningful to us, now. As Dewey puts it, “Only imaginative vision elicits the possibilities that are interwoven within the texture of the actual. The first stirrings of dissatisfaction and the first intimations of a better future are always found in works of art.”[34]

Artists have been critical voices in cultural formation, questioning how we perceive, feel, think about, and imagine the world—as it exists and as it might exist. Even the most radical questioning of a society’s status quo recognizably comes from a shared, human standpoint. Could AI art, autonomously produced, speak from this standpoint? Who or what would be the agent? What could its intention or motivation possibly be? If AI continues to function by drawing, parasitically, upon patterns that already exist in its data samples—assuming, with trepidation, that such samples are fair and representative ones—then how can we expect it to break from what is already conventional and habitual? And how would it choose which direction to break?

These questions are obviously rhetorical. The point is simply that if art has this critical and constructive role, then art seems categorically ill-suited to be something AI can make. Technologies of this sort, used autonomously, put the preservation and creation of meaning at risk.

5. Technology and empathy

Threading through the various dimensions of meaning creation and preservation, by inquiry, by memory, by art, is a distinctly human piece—empathy. Without accounting for this factor, we lose sight of the fact that technologies are never just superadded to our lives; they interweave with life. As Shannon Vallor notes, we live through technology, and we are changed by what we live through: “Technologies neither actively determine nor passively reveal our moral character, they mediate it by conditioning, and being conditioned by, our moral habits and practices.”[35] These new conditions affect empathy. Speed, distraction, and fragmentation add new habits that work against our capacity for empathy. Drawing on the work of psychologist Daniel Goleman, Vallor writes, “For media multitaskers their resulting distractibility may be significant obstacle to [empathic concern] for there is evidence that the neural mechanisms of attention that produce empathic moral concern require considerably more time to activate than others.”[36] The point is that technologies shape moral character via our attentional capabilities; to put it bluntly, one just cannot be empathetic if one is learning to not pay attention. Writing about our habits with smart phones, Vallor notes: “Looking up every few minutes to make a second or two of eye contact is unlikely to be sufficient either to accurately read another’s emotional state or to activate…empathic concern. [I]n addition to empathy, bottom-up processes of moral attention facilitate other important virtues, such as flexibility, care, and perspective.”[37]

Fundamental to morality, then, is the ability to see things from another’s perspective; only then can we investigate what to do. John Dewey defined empathy as “entering by imagination into the situations of others,” and this is something frustrated by the level and kind of involvement with technology described above by Vallor.[38] For Dewey, as Steven Fesmire notes, “empathy is a necessary condition for moral deliberation [and] provides the primary felt context of moral reflection, without which we would not bother…seeing what is…possible in a situation.”[39]

Though she does not name Dewey, psychologist and technology critic Sherry Turkle emphasizes this precise phenomenon in her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation:

Research supports what literature and philosophy have told us for a long time. The development of empathy needs face-to-face conversation. And it needs eye contact….We’ve seen more and more research suggest that the always-on life erodes our capacity for empathy. Most dramatic to me is the study that found a 40 percent drop in empathy among college students in the past twenty years, as measured by standard psychological tests, a decline its authors suggested was due to students having less direct face-to-face contact with each other. We pay a price when we live our lives at a remove.[40]

My point here is simply that the preservation of meaning depends on empathy as much as on other factors, such as inquiry. Empathy is an embodied, physical, situated, and sensorial process that depends on our attentional habits. Insofar as new technologies and devices are disembodying, while also increasing our distractibility and inattention to others, we will suffer greater obstacles to empathy—and to preserving meaning.

Conclusion

This essay aimed to raise questions about the capacity of new technologies to preserve meaning, including aesthetic meaning. While I am not anti-technology, I do believe it is incumbent on philosophers and those researching and educating about aesthetics to raise difficult and skeptical questions. The goal is to help safeguard what is worth preserving.

The following points have hopefully been established:

First, that changes in technology bring with them changes in habits, including patterns of relationships, skills and capacities, and moral habits. Technology affects meaning because, as Borgmann and Dewey point out, it emerges from and alters our social and cultural world. The critical thing is to be aware of how and why this is happening. These changes affect art and artistic production, profoundly, and bear directly on academic aesthetics.

Second, that there are new technologies with operating procedures premised on influencing our feeling, thinking, and conduct. The more obvious examples are algorithmic, but these newer technologies are part of a longer trajectory, which Borgmann labels the “device paradigm.” Devices, old and new, have the capacity to alter habits, including those that have involved focal things and practices that make life meaningful.

Third, new technologies also have the power to weaken habits—epistemic, memory, empathy—integral to conducting inquiry. Such inquiry is not just about calculative problem solving but is how we remain creative agents of a future worth wanting.

Finally, there is real cause to worry about an empathy gap developing as a result of the new habits these technologies condition. Because empathy is critical to the foregoing — inquiry, practice, and art making/appreciation—we are well-advised to remain engaged with the regulation, and even the constriction, of technologies that work against our values.

David L. Hildebrand

hilde123@gmail.com

David L. Hildebrand is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Colorado Denver. His current research focuses upon the aesthetic, pragmatic, and ethical implications of digital and AI technologies, and also upon John Dewey and pragmatism. He is a past president of the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy and the Southwest Philosophical Society.

He is presently co-editing the Cambridge Critical Guide to John Dewey’s Experience and Nature in honor of that work’s centennial anniversary.

Published on July 14, 2025.

Cite this article: David L. Hildebrand, “Preserving the Meaning in an Age of Algorithms and AI,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 13 (2025), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] Tools classed as AI include a wide range. To list just a few, by rough category, there are translation, recognition, and search tools, which include machine translation (such as Google Translate and DeepL), speech recognition/speech to text/dictation tools (such as Otter AI, Dragon, and Whisper), speech generation/text to speech (such as Speechify and Polly), image recognition (such as Image GPT and Photor.io), and AI-powered search engines or research tools (such as Perplexity and Scopus AI). There are also what one might call “summarizing, checking, organizing” tools: anti-plagiarism (such as Copyscape, Copyleaks, and Turnitin), reference management (such as Mendeley), summary (such as Explain Paper, Tavily AI, and Consensus), writing assistants (such as Grammarly), note taking (such as Notion, Scribe). More ambitiously, there are relationship tools: friendship (such as Nomi, Kindroid, Replika, Character.ai, and Candy.ai), and therapy tools (such as Woebot). Finally, there are creative tools, including those generating text (such as ChatGPT, Bing Copilot, Bard), images (such as DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and Firefly), music (such as Soundraw, Musicfy.lol, and Mubert), and code (such as Llama 2, GPT-4, Mistral, and Claude).

[2] Because work on this topic has been my focus over the last few years, this article draws upon the following pieces, where I, David L. Hildebrand, am the sole author: “What Are Data and Who Benefits,” in Framing Futures in Postdigital Education. Critical Concepts for Data-driven Practices, eds. Anders Buch, Ylva Lindberg, and Teresa Cerratto-Pargman (Cham: Springer, 2024); “Democracy without Autonomy? Information Technology’s Manipulation of Experience and Morality,” in John Dewey and Contemporary Challenges in Education, ed. Michael G. Festl (New York: Routledge, 2025); and “Philosophical Pragmatism and the Challenges of Information Technologies,” The Pluralist,18:1 (2023), 1-9.

[3] Roberta Dreon, Human landscapes: Contributions to a Pragmatist Anthropology (New York: State University of New York Press, 2022), 3.

[4] Charles S. Peirce, “The Fixation of Belief,” in The Essential Peirce, Volume 1: Selected Philosophical Writings (1867–1893), eds. Nathan Houser and Christian Kloesel (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), 109-123.

[5] See Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other (New York: Basic Books,2011), and also Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (New York: Penguin Press, 2015).

[6] Turkle draws attention to solitude’s renowned connection to creative work: “For Kafka, ‘You need not leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. You need not even listen, simply wait, just learn to become quiet, and still, and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked.’ For Thomas Mann, ‘Solitude gives birth to the original in us, to beauty unfamiliar and perilous—to poetry.’ For Picasso, ‘Without great solitude, no serious work is possible.’ (Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation, 67). Clearly, then, changes due to technology to the extent and quality of solitude is germane to how we research and educate about art and aesthetics.

[7] Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: Public Affairs, 2019).

[8] Ibid., 199.

[9] Will Oremus writes, “What saved the like button was, in true Silicon Valley fashion, an appeal to data. In a test, Facebook data analysts found that popular posts with the button actually prompted more interactions than those without…But coding the like button involved much more than just drawing it. Each like had to be stored in databases that linked it to both the post itself and the person doing the liking…The like button was an instant hit, and Facebook soon found ways to ingratiate it into the fabric of not just its platform, but the internet beyond.” See, Will Oremus, “How Facebook Designed the Like Button—and Made Social Media into a Popularity Contest,” Fast Company, (11/15/2022) https://www.fastcompany.com/90780140/the-inside-story-of-how-facebook-designed-the-like-button-and-made-social-media-into-a-popularity-contest.

[10] On challenges involving data scarcity and “model collapse,” see Rice University, “Breaking MAD: Generative AI could Break the Internet, Researchers Find,” ScienceDaily (7/30/2024), https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/07/240730134759.htm. On the energy costs of generative AI, see Brian Calvert, “AI already uses as much energy as a small country. It’s only the beginning,” Vox (3/28/2024), https://www.vox.com/climate/2024/3/28/24111721/climate-ai-tech-energy-demand-rising.

[11] Interview with Zuboff. Catherine Tsalikis, “Shoshana Zuboff on the Undetectable, Indecipherable World of Surveillance Capitalism,” CigiOnline,(8/15/19), https://www.cigionline.org/articles/shoshana-zuboff-undetectable-indecipherable-world-surveillance-capitalism/).

[12] Zuboff, Age of Surveillance Capitalism, 200.

[13] See John Danaher, “Freedom in an Age of Algocracy,” in The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Technology, ed. Shannon Vallor (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 265.

[14] Ibid., 265.

[15] See Tom O’Shea, “Disability and Domination,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 35, no. 1, 133-148. This reference in Danaher, “Freedom,” 266.

[16] Albert Borgmann, Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life: A Philosophical Inquiry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 42.

[17] Ibid., 41.

[18] Writing about the way that musical information tends to be compressed and concealed in technological delivery systems, such as records or compact discs, Borgmann states: “Records, however, submerge the full structure of information more resolutely even than writing and occlude the place, the time, the ardor, and the grandeur that provide the setting for the musical realization of structure. For a score to become real, it requires not only its proper place and time but also a communal tradition of extraordinary discipline and training. Human beings need to struggle with the recalcitrance of things and the awkwardness of their bodies before the ease and grace of music making descend upon them. The physical reality of a flute enforces stringent demands on the posture, the breathing, and the embouchure of the student. The violin re- quires that players place their fingertips on the uncharted territory of the finger board with a precision of fractions of a millimeter. Ordinary mortals need forceful teachers and many years of practice to learn these skills.” Albert Borgmann, Holding On to Reality: The Nature of Information at the Turn of the Millennium (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 103.

[19] Borgmann, Technology, 42. Chapter 23 has an extended discussion of focal things and practices.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Commenting on Renoir’s landscape paintings, Scruton singles out factors that elevate art above mere technological outputs:

“Take as an example a landscape by Renoir. Whatever is happening in that landscape, it is imbued with a sense of peace and order, and takes from the surrounding colors the vitality that brings it to life. But Renoir, like other impressionists, painted a world to which we belong. Belonging is an all-important aspect of human experience….And that is what you see in a beautiful landscape by a painter like Renoir. These are ordinary trees—fruit trees—with an ordinary mountain in the distance, and so on; but the painter shows them as part of a world to which we belong….[O]ur world is…imbued with its own tranquility and that tranquility can reside in perception itself. That is what Renoir is telling us. He says, ‘Stop, stand still, and look.’ And in that perception, you will see that this thing right in front of you that you belong to it. So there is a moment of standing still that we all can achieve and which involves letting the otherness of the world dawn on us. The world is other than me—not just imagined by me—but there in front of me and including me nevertheless.

“When painters do this…they do not behave as photographers behave. This is something which is very difficult to explain to people these days because everybody goes around with a smart phone or some such technological apparatus, immortalizing the ephemera of their existence, and as a result desecrating it with their own trivial perceptions. Renoir was not doing that at all. He was not pointing a camera at that landscape; maybe the landscape did not entirely look like that. He was trying to extract from it what it means; and what it means not just from the perceptual point of view but spiritually.” Roger Scruton, “Beauty and Desecration,” Quaestiones Disputatae, no. 6:2 (Spring 2016), 151-52.

[22] Regarding the general thesis by Borgmann of the device paradigms, some philosophers of technology, such as Peter Paul Verbeek, have challenged Borgmann’s thesis (and his concomitant call to return to “focal practices” as a way of avoiding alienation). Verbeek argues that Borgmann overextends his concern about consumptive technologies too far, raising alarm unnecessarily. See Peter-Paul Verbeek, “Devices of Engagement: On Borgmann’s Philosophy of Information and Technology, Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology, 6:1 (Fall 2002), 48-63, https://doi.org/10.5840/techne20026113. However, in my view, the rapid rise of generative AI and the enthusiasm with which it is being greeted for nonconsumptive tasks, including creative and intellectual ones, gives some argumentative weight back to Borgmann’s point about the systemic momentum of something like a “device paradigm.”

[23] These phases of inquiry are really common knowledge, and we often see it featured in popular entertainment such as detective stories. In many murder mysteries, there is a dramatic scene where the detectives or police are trying to “get a sense”—a feeling—about what the problem is, or they find themselves stuck and unable to proceed. Something about the inquiry either lacks feeling or is mismatched with the initial feeling. The “felt” phase of inquiry needs to be thickened.

[24] See John Dewey, Art as Experience in The Later Works, 1925-1953. Volume 10: 1934, ed. Jo Ann Boydston (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1981), 277.

[25] John Dewey, “Memory and Judgment,” in John Dewey: The Later Works, 1925-1953. Volume 17: 1885-1953, ed. Jo Ann Boydston (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press), 323-335, ref. on 325.

[26] This impact is well captured by Robert Innis’ comment about Dewey’s concern with modern industrial conditions’ impact on the experience of the work of art: “For Dewey the loss of aura is due to the leveling-out and gradual disappearance of the funded elements from past experience.” See Robert Innis, Pragmatism and the Forms of Sense: Language, Perception, Technics (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 185.

[27] A plethora of studies are being done. See, e.g., H.H. Wilmer, L.E. Sherman, and J. Chein, “Smartphones and cognition: A review of research exploring the links between mobile technology habits and cognitive functioning,” Frontiers in Psychology, no. 8 (2017), 605,. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00605. On GPS and memory, see Rebecca Seal, “Is Your Smartphone Ruining Your Memory? A Special Report on the Rise of ‘Digital Amnesia,’” The Guardian, (7/3/22), https://www.theguardian.com/global/2022/jul/03/is-your-smartphone-ruining-your-memory-the-rise-of-digital-amenesia.

[28] Dewey, Art as Experience, 31.

[29] Ibid., 10-11.

[30] Ibid., 19.

[31] Ibid., 20.

[32] Ibid., 70, 218.

[33] I should be clear that here I’m thinking of cases where AI is mostly (or, someday, totally) in control of the artistic creation. Artists have always used technologies to modulate their expressive outputs. Artists working with AI today, such as Sam Swift-Glasman, note how well AI can capture patterns, thus creating “useful assets” for the making process. Such assets, though, are new kinds of pieces for the puzzle he devises. On “useful assets,” see Sam Swift-Glasman (Megasets), “The Work of Art in the Age of AI: Walter Benjamin for the 2020s,” YouTube (5/5/2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sImtHyNQdPo. Another artist using AI is Holly Herndon, an electronic musician and performance artist; Herndon developed Holly+, a machine-learning model able to “translate any audio file—a chorus, a tuba, a screeching train—into Herndon’s voice.” Herndon anticipates that this model represents the future “for music, art, and literature: a world of ‘infinite media,’ in which anyone can adjust, adapt, or iterate on the work, talents, and traits of others….[a] process of generating new media” Herndon calls “spawning,” which is distinct from other allusive forms: “sampling, pastiche, collage, and homage.” See Anna Wiener, “Holly Herndon’s Infinite Art,” The New Yorker (11/13/23), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/11/20/holly-herndons-infinite-art. Again, here we see that Herndon is using machine learning to her own ends; she sees herself as an advocate for artists’ autonomy in a world increasingly shaped by AI.

[34] Dewey, Art as Experience, 348.

[35] See Shannon Vallor, Technology and the Virtues: A Philosophical Guide to a Future Worth Wanting (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 184, 173.

[36] Ibid., 171.

[37] Ibid.

[38] See John Dewey, Ethics. The Middle Works, 1899-1924. Volume 5: 1908, ed. Jo Ann Boydston (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 150.

[39] Steven Fesmire, Dewey (London: Routledge), 133.

[40] Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation, 170, 171.