The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

Prompting Aesthetic Ideologies of Generative Text-to-Image AI

Lotte Philipsen

Abstract

In generative AI, text-to-image prompting has gained popularity, which calls for image theoretical attention. This article evokes critical image theory, developed by Norman Bryson and W. J. Thomas Mitchell in the 1980s and 1990s, which offers important, relevant nuances when analyzing contemporary AI image-tools. By investigating specific cases of text-to-image AI through this theoretical filter, the article demonstrates how certain aesthetic ideologies—especially perceptualism, the idea of natural images, and splitting and hierarchization of text and image—govern generative AI.

Key Words

aesthetic ideology; generative AI; image theory; perceptualism; text-to-image aesthetics

1. Introduction

A popular practice in the field of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) is to create images by text prompting. In popular GAI image tools such as Dall-E, Stable Diffusion, or Midjourney users are invited to type a text describing the image they would like to generate, and the computer model then processes the text. Put very simply, the conversion of text into image happens in the following manner: The computer model automatically and without the user’s knowledge slightly adjusts the words and phrases according to its embedded biases; then, it compares them to text bites it already holds in its vast multidimensional and multimodal (text, images, sound) latent space; calculates which adjecting pixel combinations will most probably correspond to the text; creates one or more possible images; and finally displays one or more of those images on the user’s screen. Even though these images very often look like photographs, the proper analogy is to describe them as paintings, by hand or mouse/keyboard, painted with pixels by a computer model.

While the technical process remains hidden from the lay user and even is partly opaque to computer scientists—and is not the focus of this article—this practice is highly relevant for the field of aesthetics because it reactivates significant questions about the relations between text and images. The overall claim of this article is that even at a time when technically text and image are transformed to similar datapoints in the latent space of brand-new diffusion models, it is highly relevant to dive into key concepts of poststructuralist image theory because they provide us with a nuanced understanding of the aesthetic ideologies governing contemporary text-to-image GAI. The notion of ideology is used in a broad sense in this article— for example, as governing systems of belief about relations between images and what they depict that are at work in popular AI image tools. Ideology is not necessarily false or negative, but the notion is used here to highlight the cultural constructs at work in AI practices that are promoted as natural and neutral.

A concrete image will serve to illustrate the theoretical investigation throughout the article. When preparing a paper for a conference, I randomly fooled around in Midjourney and asked for an image of “A group of scholars gathered at The Nordic Society of Aesthetics conference in Iceland.” The tool gave me four different images, which is Midjourney’s default response (Figure 1).

The images are Midjourney’s visualizations of this textual input, or, to be more precise, they are four out of infinite possible visualizations that Midjourney will generate out of this specific text prompt. In this sense, each image is unique and original. Even though the images are relatively similar, on a personal level I found one of the four images to be particularly intriguing (Figure 2).

Hence, whereas we text-prompt the tool to create an image, the image tool prompts us to pass an aesthetic judgment insofar as it asks us to either choose between four different images that we then can additionally adjust and refine according to what we have in mind, or to reject all of them and retry with the same text-prompt that will result in four new images, or try a different prompt in our attempt to approximate a visual manifestation on the screen to what we have in our minds.

I know this picture is not a photograph, but having looked at it for a while, I must admit that my subconscious mind began to implicitly treat the picture almost as if it were a photograph documenting a real scene; even though it is not a photograph, it is photographic.[1] I really like these fellow conference participants who are professional, down-to-earth, relaxed, and friendly. I imagine that we all met at the conference and have gotten to know each other during the last couple of days—this picture is taken after the last session of the day, and we are now spontaneously going for a drink at a cozy bar to informally continue the academic discussions. Not even the gray, Icelandic weather can bring us down. In other words, much to my academic regret, the picture successfully drags me into its inner territory where my feelings yield to its visual logic and biases.

Important work has investigated how GAI image practices are not just technical but also inevitably entangled with cultural issues of copyright, capitalism, racism, working conditions, data harvesting, privacy, and so on.[2] Following this scholarly line, it is easy to criticize our example image: By default, it mimics the visual language of photography, thus favoring the expression of one specific cultural and historical media over others; it expresses a specific visual understanding of what Iceland looks like; and it certainly has a very narrow scope of imagining the ethnicities of “scholars.” In addition to the technical-cultural take on GAI images, the field of contemporary image theory enables us to understand how digital images today are networked and operative in different manners than traditional images.[3] The networked-ness and the operative-ness of GAI images are aesthetically relevant because both involve how we perceive, use, and are affected by the AI image practices. But rather than exploring the technical, the cultural, or the contemporary image theoretical dimensions of GAI images, this article aims to supplement them by claiming that with text-to-image prompting, it becomes highly relevant for the field of aesthetics to revisit the parts of more traditional, poststructuralist image theory that critically discusses the concepts of “the discursive” vs. “the figural”; the “essential copy”; “image” vs. “picture”; “mental” and “verbal” images; and the “artificial” vs. the “natural.” Therefore, in the following, the article specifically analyzes the text-image relation in contemporary GAI images through the theoretical work developed in the 1980s and 1990s by Norman Bryson and W. J. Thomas Mitchell.

The match may seem odd. Why not investigate text-image relations in GAI by use of more contemporary theory? What renders Bryson and Mitchell’s work particularly pertinent is that they both thoroughly analyzed relations between text and image. They did so from an image theoretical point of view at a time when the discipline of art history was lacking critical image theory, so they challenged existing image ideologies in traditional art history—this required meticulous and convincing work. As this article hopes to demonstrate, the thoroughness of Bryson and Mitchell’s work on text-image relations makes it suitable for nuanced analysis of the aesthetic ideologies of popular GAI images. Hence, the article through its analytical work also suggests that one important way for the academic discipline of aesthetics to relate to AI would be to go deep on aesthetic theory in order to analyze AI phenomena from perspectives that other disciplines are not able to apply.

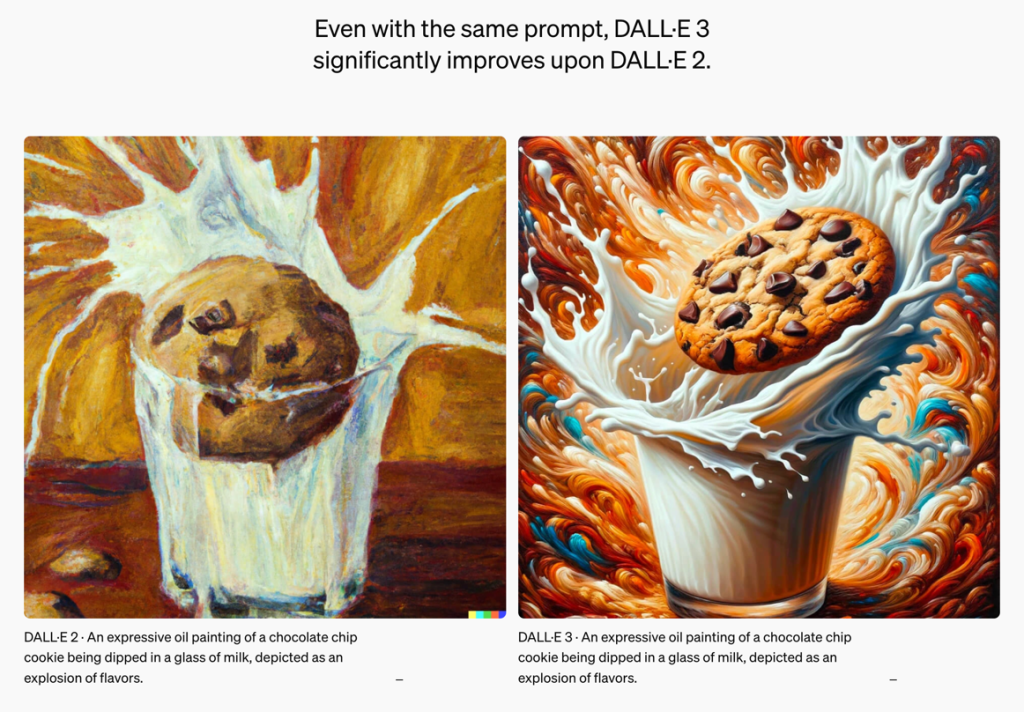

2. GAI pictures’ natural attitude

The renewed pertinence of Norman Bryson’s work can be demonstrated by a statement from OpenAI, who developed the popular GAI image model DALL-E. In October 2023, OpenAI released their third version of DALL-E and proudly announced that “Even with the same prompt, DALL-E 3 significantly improves upon DALL-E 2” (emphasis added).[4] OpenAI demonstrates the improvement by showing how the two models respond to the text prompt, “An expressive oil painting of a chocolate chip cookie being dipped in a glass of milk, depicted as an explosion of flavors” (see Figure 3).

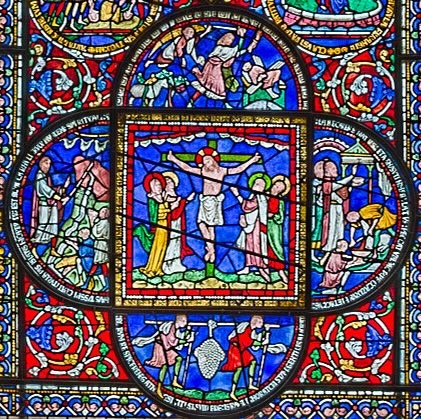

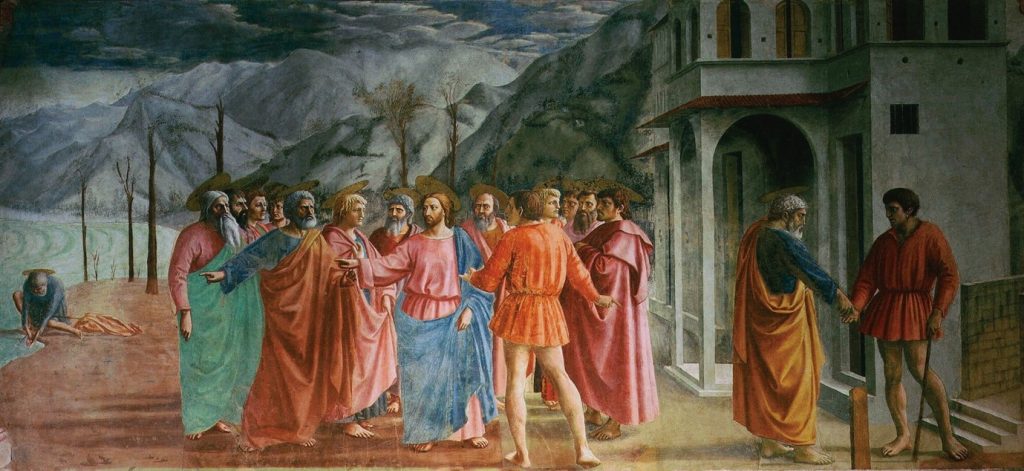

To understand the aesthetic logic at work here, Bryson’s critique of the “natural attitude” and the “essential copy” is highly relevant—even if his examples and object of study stem from art history rather than popular culture.[5] Bryson argues against the view “found in the ‘traditional’ account of the development of European painting as a series of technical leaps towards an increasingly accurate reproduction of ‘the real’,”[6] and as an example, he compares two specific pictures: a stained-glass window from the 1180s (Figure 4) and a fresco painted in 1425 (Figure 5).

Traditional art historical image theory would consider the fresco painting, with its use of linear perspective, many details, and light/shadow nuances creating plastic illusions, to be more realistic than the stained-glass window, based on an argument that the fresco to a higher degree resembles the real world as we see it with our own eyes. As Bryson convincingly argues, the problem with this approach is that it rests on the idea that the pictures depict a real, objectively observable, natural world that exists outside and before the picture. This is what Bryson refers to as “the natural attitude”: “Within the natural attitude […] the image is thought of as self-effacing in the representation or resurrection of things, instead of being understood as a milieu of the articulation of the reality known by a given visual community.”[7] Exemplified with our images, Iceland and chocolate chip cookies are natural phenomena and there never is, or has been, a need to discuss what they are. To depict such “natural” phenomena is a matter of visually perceiving them in an objective manner and aiming to create what Bryson refers to as an “essential copy.” Hence, even when paintings depict scenes that the painter has not eye-witnessed, like the scenes from the Bible represented in the stained-glass window and the fresco,[8] details in the motive are assumed to be the result of the painter’s human eye having perceived visual phenomena in an objective manner. Bryson refers to this as a “perceptualism” that haunts the history of European painting. According to Bryson, seeing things—a house, a scholar, a mountain—is not a matter of perception but a matter of recognition, which is a social practice that always (though not simultaneously) involves more than one person. He states: “Perhaps the most negative consequence of perceptualism is its bracketing-out of the constitutive role of the social formation in producing the codes of recognition which the image activates.”[9] In other words: Perceptualism black-boxes the codes of recognition and prevents discussion about what societal mechanisms resulted in “Jesus,” or “conference,” or “milk” being depicted in this manner.

When visual conventions are considered to be natural, their historical context is disregarded and it is possible to judge pictures created within different cultural and historical codes of recognition according to a single, imagined concept of objective perception. Bryson demonstrates how this mechanism is at work in traditional art history, where it results in the idea of a historical artistic strive towards the essential copy and forms an ideology of perfection, meaning that progress, not change, explains why artistic styles differ from one period to another. Bryson compares this thinking in traditional art history to Karl Popper’s scientific concept of falsification, in the sense that artists in general encounter a problem (how to “truthfully” and mimetically depict the natural world), try out solutions, fail, eliminate errors, try again, fail in other respects, eliminate errors, try again, and so on, in a continuous, historical process of optimization and approximation towards the fantom of the essential copy.[10] Only within this traditional paradigm is the fresco considered more realistic than the stained glass window picture.

OpenAI’s praise of DALL-E 3 evidently is governed by the natural attitude to the extent that it only states that, compared to DALL-E 2, significant improvement has taken place, without mentioning what kind of improvement we are dealing with. “Improvement” in terms of what? one might ask, but the ideology of essential copies of unambiguous phenomena is so pervasive that it would seem unnecessary to state that the underlying belief is “improvement in terms of how things really are.” According to this logic of visual optimization, the image produced by DALL-E 3 is not just different from the one produced by DALL-E 2, it is also better, and future versions of the model will produce even better pictures of “An expressive oil painting of a chocolate chip cookie being dipped in a glass of milk, depicted as an explosion of flavors.” (see Figure 3). Hence, the idea of visual improvement rests on an opaque idea of the ultimate, “true” image.

In addition to naturalizing codes of visual recognition, in the DALL-E example naturalization also takes place at the level of the pictorial motif. When one considers the variety of contemporary pressing issues that call for visual attendance, DALL-E’s prompt example fully demonstrates how casual leisure, driven by an ideology of experience economy,[11] seems to be the key affordance of the tool. “Expressive oil painting of a chocolate chip cookie…,” along with similarly silly prompt examples from DALL-E like the “avocado armchair” and the “astronaut riding a horse,” are so innocent and inoffensive that they anaesthetize any sense the user might have of images’ potential power for societal changes, for instance, serving to represent minorities, visualize opaque structures, or promote alternative views. OpenAI’s emphasis on the model’s technical capabilities—on the possibility of creating the picture—is so strong that it represses consideration on whether we need or want this picture.

3. Imagetext

We now turn to the theoretical work of W. J. Thomas Mitchell, taking as a starting point his concept of “imagetext,” which “designates composite, synthetic works (or concepts) that combine image and text”[12] and is well-suited to shed further light on aesthetic mechanisms at work in text-to-image GAI. The concept aligns with Mitchell’s thorough investigations of the multimodality of images—encapsulated in his statement that “There are no visual media… [because]… all media are mixed media” (original emphasis).[13] In the previous section, I deliberately used the term ‘picture’ to describe the different, concrete examples, but with Mitchell we are able to nuance this thanks to his highly useful distinction between image and picture in his book, Picture Theory (which he interestingly called a “prompt-book” thirty years ago[14]). Whereas a picture is: “a constructed concrete object or ensemble (frame, support, materials, pigments, facture)”; “a deliberate act of representation (‘to picture or depict’)”; and “a specific kind of visual representation (the ‘pictorial’ image)”, an image is: “the virtual, phenomenal appearance that [the picture] provides for a beholder”; “a less voluntary, perhaps even passive or automatic act (‘to image or imagine’)”; and “the whole realm of iconicity (verbal, acoustic, mental images).”[15] Especially the broader notion of the image is of relevance here, and it was nuanced by Mitchell in his earlier book, Iconology, which is helpful when investigating our Icelandic example.

Mitchell analyzes how images can operate as agents to create likeness/resemblance/similarity by subdividing the overall concept of the image into a range of different kinds of images: graphic (pictures, statues, designs—note how pictures are only a minor sub-element in Mitchell’s overall image system); optical (mirrors, projections); perceptual (sense data, “species,” appearances); mental (dreams, memories, ideas, fantasma); and verbal (metaphors, descriptions).[16] Mental and verbal images particularly seem relevant for text-to-image GAI because they offer theoretically nuanced descriptions of the instance where a GAI tool user has a (vague) idea in mind (“I wonder what an AI-generated image of the up-coming conference would look like”) and then converts this mental image into a verbal image in the stage of composing the actual text prompt. Hence, in GAI, graphic images arriving on our computer screens are deeply entangled with mental and verbal images and are the results of an aesthetic ideology of Midjourney, Dall-E, and other tools to erase variances and disagreement among these different kinds of images and force similarity upon them. In this sense, they are conceptualized as what Mitchell calls transcendental objects:

…we should note that these ideal objects—forms, species, or images—need not be understood as pictures or impressions. These kinds of ‘images’ could just as well be understood as lists of predicates enumerating the characteristics of a class of objects, such as: tree (1) tall, vertical object; (2) spreading green top; (3) rooted in the ground.[17]

In this example, the conceptual character of the ideal object “image” tree resembles (traditional) programming governed by strict rules and syntax, and the difference between Mitchell’s description and a GAI image (based on deep leaning) is that Mitchell offers insights into the three parameters constituting his tree, whereas in GAI image tools, such parameters would be hidden in the deep neural networks of an opaque training process.[18] Prompting “tree” with no further elaboration or definition would be sufficient to generate a picture (Figure 6).

In this particular example, we know the verbal image (the text prompt “tree”) and the graphic images we can see (Figure 6), but any individual mental image we may have of “tree” are likely created in the following manner: We read Mitchell’s parameters above—‘(1) tall, vertical object; (2) spreading green top; (3) rooted in the ground)’—and most likely adjusted or negotiated them in our minds as an effect of Midjourney’s graphic images. Hence, our sensuous encounter with the graphic image gives rise to an aesthetic experience in the form of a projected triangular dialogue between our subjective expectations, the graphic images, and the verbal image. Following aesthetic theory in the Kantian sense,[19] one could argue that the imagetext aspect of GAI images as it plays out in practice holds potentials for deeper aesthetic experiences than OpenAI’s focus on chocolate chip cookie “improvement” demonstrates. The process of text-to-image prompting evokes a variety of subjective aesthetic judgements because the tools—with their biases and hidden training material— “kick back” and surprise, annoy, challenge, thrill, and frustrate our mental images.

This may also occur in a reversed process of image-to-text prompting, in which the user uploads an image to which the GAI tool responds with text describing the image. Prompting our Icelandic example (Figure 2) to Midjourney results in four different, short descriptions. From the descriptions, we learn among many other things that: the picture is definitely a photograph (down to the exact camera model and the specific lens); it is unclear how many people are in the picture (six, nine, or a “group”); people all wear black shoes; and they are from Norway.[20] In this case, the graphic image from us results in verbal images from Midjourney, which results in heavy activity (re)negotiating our mental image(s) as we compare the text descriptions with the image we uploaded. The classic aesthetic features of indeterminacy and pondering questions of purposes are part of this activity. It seems unlikely that development teams behind popular GAI image tools studied Mitchell’s Iconology, but the popular notion in the industry of text-to-image, and not text-to-picture, is highly precise.

4. Text over image

Even if mental, verbal, and graphic images are deeply entangled in GAI images, in the discourse of computer science and Big Tech, they are not considered to be on the same hierarchical level. Text is valued higher than pictures, which aligns with a traditional assumption critically scrutinized by both Bryson and Mitchell—so let us take a look at their critique first.

The foundation of the hierarchical relation between text and picture lies in the general traditional assumption, elaborated above, that pictures are code-less signs: Following the logic of a natural attitude, as depictions they are seen to strive for being essential copies of the world. With Bryson, we have established that painting cannot be “calibrated by degrees of remoteness from, or approximation towards, an Essential Copy…[because]…there is no Essential Copy.”[21] The question, then, is why does the ideal of an essential copy hold such a strong predominance (as we have seen with OpenAI)? Bryson offers a helpful explanation that involves the concepts of the discursive and the figural: The discursive is “those features which show the influence over the image of language”[22]—this could be, for instance, wall labels in galleries, biblical scripture (in the case of the stained glass window and the fresco), or text prompts in GAI images—and the figural is “those features which belong to the image as a visual experience independent of language”[23]—the visual aspects we appreciate if there is no wall label, or if we do not know the biblical script or the text prompt. Explained in Mitchell’s terms, an imagetext triangle always consists of graphical, verbal, and mental images, but the discursive is focused on the relation between the mental and the verbal images, whereas the figural is focused on the relation between the mental and the graphical images. Put briefly, the discursive relates to text, and the figural relates to pictures.

According to Bryson, in the attempt of European Renaissance painting to break free from the dispositive of biblical semantic symbols, figural aspects were enforced in pictures to the extent where the Masaccio-fresco (Figure 5) “succeeds in creating a threshold between two informational areas: on the one side of that threshold, semantic necessity, and on the other, semantic irrelevance” (emphasis added).[24] An important tool in creating such a threshold between symbolic text and ‘innocent’ visual elements is the use of perspective,[25] as formally conceptualized by Leon Battista Alberti in 1435. A similar observation is made by Mitchell, who describes pictures that make use of artificial perspective as tyrannous, because they are responsible for the fact that

We imagine the gulf between words and images to be as wide as the one between words and things […] The image is the sign that pretends not to be a sign, masquerading as […] natural immediacy and presence. The word is its ‘other,’ the artificial, arbitrary production of human will that disrupts natural presence by introducing unnatural elements into the world…[26]

The conceptual understanding of text as cultivated, human, symbolic, and artificial contrasted by an understanding of images as natural is relevant to GAI images because technically texts and pictures coexist as the same type of data in the latent space of diffusion models—they are both mathematical numbers.[27] Only in their practical function—when applied to specific interfaces (Midjourney on Discord, Dall-E in ChatGPT, and so on) that are designed to translate a specific type of input from the user (here, text) to another specific type of output to the user (image)—are they provided with different media formats. GAI tools thus (re)create the conceptual “gulf between words and images” in the user interface only to offer their services as a help to bridge this conceptual gulf. The “gulfing” is also demonstrated by the research and development focus on building large language models (LLMs) founded on natural language processing (NLP).

Natural language processing (NLP) is an all-important concept in the LLMs that constitute a fundamental part of contemporary text-to-image practice.[28] Basically, NLP is an attempt to master real text—hence the “natural” prefix—and uses actual written text (parole in a broad sense), covering everything from online fora to classical literature, to train computer models in a machine learning approach, instead of a traditional programming approach that teaches the model words and grammar rules (langue in a narrow sense). As elaborated by Hannes Bajohr, in this (self)learning mode of AI, the machine learning takes place on a subsymbolic level where it does not need to adhere to rigid rules.[29] As a result, the computer model “understands” laypersons’ prompts written in an intuitively everyday manner, or at least this is the ideal; in reality, the rise of prompt engineering has proven that often users need to adjust their own intuition to the computer models’ intuition.[30] “Natural language” aimed for in computer models is comparable to what Bryson terms “realist text.” He states (with reference to Roland Barthes) that “The realist text disguises or conceals its status as a place of production of meaning […] meaning is felt as penetrating the work from an imaginary space outside it—the ‘world,’ whose intrinsic meanings are simply being transcribed.”[31] With all the resources and attention put into natural language processing in the AI industry, why has no one been engaged in what we might call “natural image processing”? The answer is simple: because the industry considers images to be natural in themselves.

Mitchell traces the idea of images’ natural character back to the philosophy of John Locke and the aesthetic theory of Edmund Burke, where images and words belong to two different aesthetic groups. In one group we have “wit, resemblance, poetry, images, primitive, obscure images,” while in the other we have “judgement, difference, prose, words, modern, clear images.”[32] The predominant attitude of GAI image tools align with the latter group, which a couple of additional statements from OpenAI may demonstrate: “DALL·E 3 understands significantly more nuance and detail than our previous systems, allowing you to easily translate your ideas into exceptionally accurate images…DALL·E 3 represents a leap forward in our ability to generate images that exactly adhere to the text you provide” (emphasis added).[33] In OpenAI’s popular description of DALL-E 3, all the traditional art theoretical assumptions that Bryson and Mitchell critically discussed and convincingly challenged forty years ago have risen from their vault, and with them an ideological foundation that Mitchell has described with such precision that it deserves a lengthy quote:

The notion of the image as a ‘natural sign’ is, in a word, the fetish or idol of Western culture… [I]t must certify its own efficacy by contrasting itself with the false idols of other tribes – the totems, fetishes, and ritual objects of pagan, primitive cultures, the ‘stylized’ or ‘conventional’ modes of non-Western art. Most ingenious of all, the Western idolatry of the natural sign disguises its own nature under the cover of a ritual iconoclasm, a claim that our images, unlike ‘theirs’ are constituted by a critical principle of skepticism [sic] and self-correction, a demystified rationalism that does not worship its own projected images but subjects them to correction, verification, and empirical testing against the ‘facts’ about ‘what we see,’ ‘how things appear,’ or ‘what they naturally are.’[34]

5. Conclusion

The point behind Mitchell’s analytical work was “not to heal the split between words and images, but to see what interests and powers it serves.”[35] This article has attempted to do so. The article’s focus is narrow insofar as it applies the theoretical optics offered by Bryson and Mitchell decades ago, to specifically analyze text-to-image GAI, with the designated purpose of investigating its aesthetic ideologies. This investigative method provides several insights.

First of all, when (re)reading Bryson and Mitchell’s work, some of their image theoretical terms stand out. Notions like “thresholds,” “functions,” “features,” “approximation,” and most significantly “natural” are important concepts in Bryson and Mitchell, but they are also central, technical terms in contemporary AI research, and in a manner of theoretical Nachträglichkeit, we are able to use these image theoretical concepts to qualify our understanding of GAI image practices. Specifically, the article’s investigation has shed light on the “natural attitude” at work in GAI, in which processing the codes of language to obtain the goal of mastering natural language is a laboring task, while images are considered to be code-less and natural from the very beginning. This image ideology of perceptualism not only black-boxes the material mechanisms of training processes and hidden adjustments of users’ text prompts but also disregard the fact that visuality and pictorial meaning result from social and historical conventions. As such, it works in direct continuation of an assumed aesthetic and cultural superiority of text over images.

Second, official promotion of popular GAI image tools speaks to a leisure- and entertainment-based use that belongs to the aesthetic category of the pleasurable, but disregards more complex, undetermined aesthetic experiences that may potentially emerge in actual practices and processes of text-to-image GAI. And finally, even though text and image are deeply entangled—in the latent space of computer models and in the aesthetic function for the user who simultaneously navigates mental, verbal, and graphic images—they are ideologically separated in the above-mentioned hierarchy, and in input/output options of user inferences where GAI tools explicitly offer translation between text and image. Rather than straightforward text-to-image (or image-to-text), the text-and-image theories of Bryson and Mitchell offer urgently needed nuances to an image theoretical discussion of the aesthetic dimensions of GAI images.

In a broader perspective, the article has pointed out an important implication of AI technology for the academic discipline of aesthetics. While the approach of digital humanities mainly applies AI methods to analyze aesthetic phenomena,[36] this article has demonstrated the productiveness of the opposite approach: The discipline of aesthetics may benefit from studying new aesthetic phenomena resulting from AI as contemporary research objects. This requires scholars in the field to approach AI phenomena with academic, critical curiosity, which includes practical, hands-on engagement and familiarizing oneself with the overall principles of AI technology, if only on a basic level. Methodologically, however, aesthetics constitutes a vast repository of theory that is relevant for critical analysis of AI phenomena.

Lotte Philipsen

lottephilipsen@cc.au.dk

Lotte Philipsen is associate professor with the School of Communication and Culture at Aarhus University, Denmark. She holds a PhD in Art History, and her research focuses on contemporary art, visual theory, and aesthetic practices that make use of new technologies and advanced science. She is co-founder and director of AIIM, Centre for Aesthetics of AI Images, and PI of the research project “New Visions: image cultures in the era of AI.”

Published on July 14, 2025.

Cite this article: Lotte Philipsen, “Prompting Aesthetic Ideologies of Generative Text-to-Image AI,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 13 (2025), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] For an elaborated analysis of the “photographic,” see Joanna Zylinska, The Perception Machine: Our Photographic Future Between the Eye and AI (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2023).

[2] See: Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen, “Excavating AI: The Politics of Training Sets for Machine Learning” (September 19, 2019) https://excavating.ai; Shoshana Zuboff, Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: PublicAffairs, 2018); Sophia Williams, “AI and Artists’ IP: Exploring Copyright Infringement Allegations in Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd.,” February 26, 2024 at https://itsartlaw.org/2024/02/26/artificial-intelligence-and-artists-intellectual-property-unpacking-copyright-infringement-allegations-in-andersen-v-stability-ai-ltd/; Federico Bianchi, Pratyusha Kalluri, Esin Durmus, Faisal Ladhak, Myra Cheng, Debora Nozza, Tatsunori Hashimoto, Dan Jurafsky, James Zou, and Aylin Caliska, “Easily Accessible Text-to-Image Generation Amplifies Demographic Stereotypes at Large Scale,” Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 1493-1504, https://doi.org/10.1145/3593013.3594095.

[3] Centre for the Study of the Networked Image, Geoff Cox, Annet Dekker, Andrew Dewdney, and Katrina Sluis, “Affordances of the Networked Image,” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, 30, no. 61-62 (2021): 40–45, https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v30i61-62.127857; Aurora Hoel, “Operative Images. Inroads to a New Paradigm of Media Theory,” in Image – Action – Space: Situating the Screen in Visual Practice, eds. Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, and Moritz Queisner (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2018), 11-28, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110464979-002.

[4] OpenAI, “Dall-E 3” at https://openai.com/index/dall-e-3/ (acessed July 14, 2024).

[5] Norman Bryson, Word and Image: French Painting of the Ancien Régime (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981, reprint 2011), chapter 1 “Discourse, Figure” and Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 1983, reprint 1995.

[6] Bryson, Word and Image, 6.

[7] Bryson, Word and Image, 8.

[8] In Word and Image, Bryson offers a thorough description and analysis of the biblical scenes depicted in both pictures.

[9] Bryson, Vision and Painting, 43.

[10] Bryson, Vision and Painting, chapter 2.

[11] Joseph B. Pine and James H. Gilmore, The Experience Economy: Competing for Customer Time, Attention, and Money (Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Review Press, 2020).

[12] W.J. Thomas Mitchell, Picture Theory (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994), 89, footnote 9.

[13] W. J. Thomas Mitchell, “There Are No Visual Media,” Journal of Visual Culture 4, no. 2 (2005): 257-266, 266, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412905054673.

[14] Mitchell, Picture Theory, 7.

[15] Mitchell, Picture Theory, 4, footnote 5.

[16] W. J. Thomas Mitchell, Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986), 9-14.

[17] Mitchell, Iconology, 33.

[18] John D. Kelleher, Deep Learning (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2019)

[19] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, (Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications, 2005 [1790]).

[20] Text descriptions of Figure 2 (generated by Midjourney, June 30, 2024):

- “A group of six people from Norway, standing in the streets and smiling at the camera, wearing business with long coats and blue shirts underneath, holding yellow notepads, some have hair that is blond or brown, one woman has blonde shoulder-length curly hair, they all wear black shoes, buildings in the background are colorful houses with grey roofs, sunny day, in the style of street photography, a raw photo taken on a Sony Alpha A7 III, a wide angle shot, depth of field.”

- “A group of people in the city center, including two women and seven men from Norway stand together for an event with their hands on hip, smiling at the camera. One woman is blonde wearing business while the other man wears a suit jacket and black pants. They hold document bags or notepads, all looking directly into the front view. In the background we see houses, street lights and blue walls of buildings. Shot taken in the style of Sony Alpha A7 III camera using Canon EF lens.”

- “A group of business people in Iceland posing for the camera, including one woman with blonde hair and a grey coat standing next to them. They stand on an urban street lined with blue buildings. The man has a short brown beard wearing a black jacket over a white shirt and dark trousers holding a yellow bag. A second person stands behind him wearing a gray sweater and scarf. On his left side is another adult male dressed as a professional designer carrying a beige pencil case. He wears glasses. There are also two young women smiling at the front of the picture. It’s sunny outside.”

- “A group of happy people in the city center, all wearing business and holding documents in their hands, standing next to each other against a backdrop of Scandinavian architecture. The buildings around them have blue or yellow walls with wooden windows. In front there is an open street with cobblestones, where they stand smiling at the camera. On one side stands another man dressed casually. It’s spring outside, a sunny day with a cloudy sky.”

[21] Bryson, Word and Image, 7.

[22] Bryson, Word and Image, 6.

[23] Bryson, Word and Image, 6.

[24] Bryson, Word and Image, 11.

[25] Bryson elaborates on notion of threshold in Vision and Painting, chapter 3; for a critique of the assumed “innocence” in the Masaccio fresco see Bryson, Word and Image, p. 11; for a critical discussion of perspective in Italian Renaissance painting see Bryson, Vision and Painting, chapter 5.

[26] Mitchell, Iconology, 43.

[27] Akshay Kulkarni, Adarsha Shivananda, Anoosh Kulkarni, and Dilip Gudivada, “Diffusion Model and Generative AI for Images” in Applied Generative AI for Beginners (Berkeley, CA: Apress, 2023), 155-177. https://doi-org.ez.statsbiblioteket.dk/10.1007/978-1-4842-9994-4_8.

[28] Dhamani Numa and Maggie Engler, Introduction to Generative AI (Shelter Island, N.Y: Manning Publications, 2024), chapter 1; Akshay Kulkarni, Adarsha Shivananda, Anoosh Kulkarni, and Dilip Gudivada, “Evolution of Neural Networks to Large Language Models” in Applied Generative AI for Beginners (Berkeley, CA: Apress, 2023), 15-31, https://doi-org.ez.statsbiblioteket.dk/10.1007/978-1-4842-9994-4_2.

[29] Hannes Bajohr, “Dumb Meaning: Machine Learning and Artificial Semantics” in Artificial Intelligence – Intelligent Art: Human-Machine Interaction and Creative Practice, eds. Eckart Voigts, Robin Markus Auer, Dietmar Elflein, Sebastian Kunas, Jan Röhnert, and Christoph Seelinger (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2024; 45-58, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839469224-003.

[30] Roland Meyer, “The New Value of the Archive: AI Image Generation and the Visual Economy of ‘Style'” in IMAGE – The Interdisciplinary Journal of Image Sciences, 37(1) (2023): 100-111

[31] Bryson, Word and Images, 9.

[32] Mitchell, Iconology, chapter 5; the two groups are listed on 122-23.

[33] OpenAI, DALL-E 3.

[34] Mitchell, Iconology, 90-91.

[35] Mitchell, Iconology, 44

[36] Katrin Brown (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Digital Humanities and Art History (London: Routledge, 2020).