The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

A Typology of Illustration

Jeffrey Strayer

Abstract

This article introduces the notions of technique-based, problem-based, and history-based illustrations as kinds of illustration relevant to art and philosophy that are intended to complement those recognized by Wartenberg. In doing so, it considers the possible illustration of different ideas within a single work, and the possibility that the complex interrelation of certain ideas may require a number of works for the success of their illustration. These different possibilities raise the issue of how illustration is related to artistic intention and understanding and to the history of art, with its settled and novel kinds of artistic production. Art as philosophy and philosophy in art are examined in relation to Modernism and Cézanne.

Key Words

history-based illustration; performative objects; pictorial equivalence; problem-based illustration; realism and idealism in art; technique-based illustration

1. Introduction

The focus of this commentary is on artworks that either raise issues with positions advocated by Thomas Wartenberg or show how to extend, in novel ways, the notion of illustrating philosophy and ideas. A work by Mel Bochner reveals that a single work of art may have parts and properties that enable it to simultaneously illustrate more than a single philosophical view. Hence, the issue is raised of how illustration relates to artistic intention and understanding. That illustration need not be confined to a single artwork that illustrates a single idea is shown by the interweaving of the complex concepts of singularity and plurality, figuration and abstraction, and time and history across the austere works of the sophisticated series, 1965/1-∞, by Roman Opalka. The division and repetition of illustration across different works can also be seen in the messier Abstract Expressionist series of work, In Plato’s Cave, by Robert Motherwell, which is focused on the concepts of appearance and reality, perfection and imperfection, and the relation of memory and knowledge. The late lily-pond paintings by Monet are considered for their relevance as historical illustrations to what came before and after them, being technique-based illustrations that show how to convert painting from being a single, stable image to a performative object, and hence functioning as forms of public examination and revelation of the relation to intention of illustration, interpretation, and time. Modernist art as philosophy is criticized in this commentary as being wrongly predicated on a single, narrow aspect of painting and incorrectly tied to Manet; thus the question is raised about how to judge its status as apt illustration if it rests on a false foundation, which raises a number of additional relevant questions. The notion that certain artists philosophize in paint is further examined in certain works by Paul Cézanne, and the relation of his work as a new kind of realism to mind and idealism is proposed and considered. It is also suggested that Cézanne’s late work includes illustration of a kind of visual composition that I call ‘pictorial equivalence,’ which has its own real and ideal dimensions. The article concludes with a brief consideration of the relation of technique-based and problem-based illustrations to the history in which they reside and help define. The thoughts considered build on the pioneering efforts of Wartenberg as they examine and possibly extend the valuable work that he has initiated.

The main purpose of Wartenberg’s Thoughtful Images is to show how certain works of art, including great works of art, can illustrate philosophy. The relation of such works to philosophy means that they point, as illustrations, to things beyond their being works of art to intellectual artifacts that they are produced to illuminate in some way.[1] An artwork can illustrate a philosophical text, concept, or theory that is said to be metaphysically primary. The work of art as illustration of an intellectual object is typically secondary.[2] For Wartenberg, though, this derivative position need not diminish a work’s artistic and aesthetic importance, and the value of a significant work of art should not be thought to suffer from its being an illustration.

Wartenberg’s work in the philosophy of illustration is important not simply for the good work that he has done in drawing attention to and analyzing salient points of relevance to conceptual or philosophical illustration. It is significant, too, for raising the question of the relation of illustration to different kinds of image; to thought; to technology; to aesthetic experience, perhaps of novel kinds; to ethics; and to kinds of self-realization, where the idea or theory to be illustrated emerges in the fact of its realization, as with Modernism and Abstract Expression, or that emerges in other ways in other kinds of art, to be considered below. While I will criticize some points made by Wartenberg in what follows, I am most interested in how his study of the relation of philosophical texts, theories, and concepts to works of art can stimulate novel ways of thinking of illustrations, including kinds of interrelated illustration to which the terms ‘problem-based,’ ‘technique-based,’ and ‘history-based’ pertain in their building on, as they include or otherwise reflect, the text-based, concept-based, and theory-based illustrations that Wartenberg has identified. In what follows, I look at these kinds of illustration and matters pertinent to them, as I consider illustration in relation to the perspectives, intentions, and understandings that they shape and to which they can be understood to respond.

2. Relations of illustrations to objects, interpretations, and ideas: divergent concepts, parts, and wholes

Wartenberg correctly maintains that certain works of art can illustrate certain philosophical ideas. One might suppose that the relation between illustration and idea here is one-to-one, so that a single artwork alone is required to illustrate a single idea and only a single idea can be illustrated by a single work. While Wartenberg does not maintain that either of these things is true, it is worth looking at this relation of artwork and illustrated idea as part of the philosophy of illustration that Wartenberg has initiated. That the latter is not the case can be seen by considering the Wittgenstein drawing, titled Range Drawing #1, by Mel Bochner. This work not only illustrates Wittgenstein’s philosophy as professed in his article, “Illustrating philosophy: Mel Bochner’s Wittgenstein drawings,”[3] but part of Karl Popper’s too. Popper believed that mathematics is invented by us, but once invented it is possible to discover things about it that are consequences of the invention that were not anticipated in its creation or that could not have been predicted to be found in it according to the purposes for which it was developed.[4] That certain numbers are irrational, for instance, is a discovery that is an unanticipated property of mathematical invention.

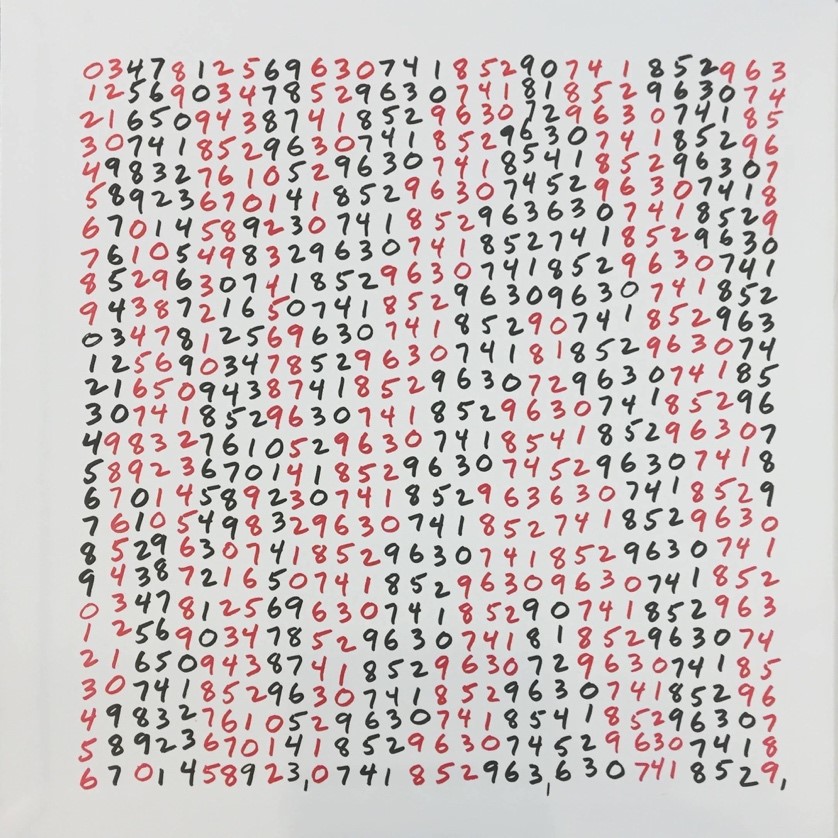

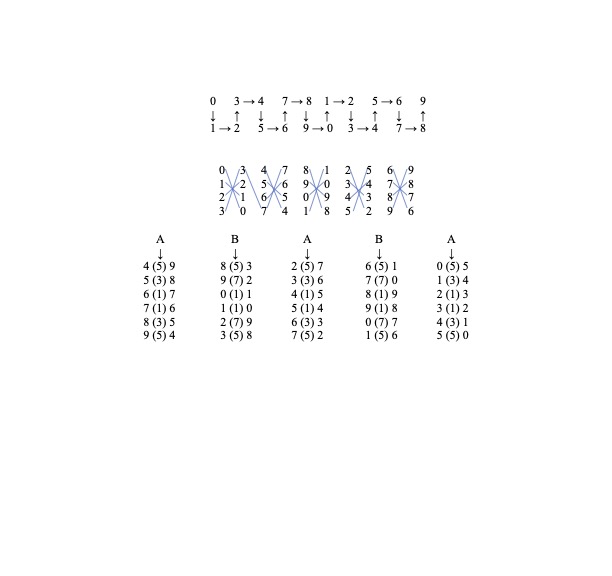

Three unintended relationships that can be found in the first ten columns of the leftmost block at the upper left of Range Drawing #1 are diagrammed below. In the first set, the arrows indicate a direction in which the numbers of the first two rows of the first ten columns follow one another: down, across, up, across, down, across, up, across, down, and so on, so that each vertical direction, up or down, is followed by the across direction moving from left to right, and the up and down directions alternate. This is not something that one would have anticipated a consequence of using the logic that Bochner used to set those vertical columns in relation to one another.

(San Francisco: Arion Press, 1991). Permission granted by the artist.

In the second grouping, there is a repeatable relation that holds among the first four numbers of adjacent columns where the order of the numbers from top to bottom is repeated in reverse order from bottom to top in the next column. And in the final grouping, which pertains to cardinal numbers at the fourth through ninth vertical position, you see that the differences in number between numbers that are paired are symmetrical from top to middle and from bottom to middle, as in the first column A, and that that same order A is repeated in the other odd pairs of related columns, three and five, that are marked A, and that the order and differences between the numbers in the even columns, marked B, are the same.

The relations cited would have been unexpected either if Bochner didn’t know of Popper’s thoughts on mathematics or knew of them but did not intend to illustrate them in illustrating Wittgenstein. The latter case is consistent with constructing a system, such as the one that Bochner used, to see what “fell out of it,” so to speak. The unexpected mathematical relations noted indicate that the same artwork can illustrate philosophical concepts and positions of different thinkers at the same time. Wartenberg has acknowledged this in correspondence and has said that he thinks that I am “correct in asserting that one work can illustrate two different philosophical claims or positions, one that it was intended to and one that it was not. It’s a parallel case to what I have called a theory-based illustration in which a philosopher uses a work to illustrate their ideas even though the artist did not so intend it. Here, Bochner might not have intended to illustrate Popper’s claim, but the work still does because of how Bochner happened to construct it.”[5] Given that one illustration is intended by Bochner and the other is not, this situation would seem to fit Wartenberg’s idea of a theory-based illustration that either works with or apart from artistic intentions. And this is the case, even though Wartenberg recognizes that “there standardly is an intention on the part of the creator of an illustration to elucidate its source in some way or other.”[6]

Jeffrey Strayer, Wittgenstein-Popper Diagram Based on Bochner

It does not matter that the points made only apply to part, rather than to the whole, of the Bochner illustration. A part of an artwork that can be understood to illustrate a philosophical concept illustrates it as much as would the whole of the illustration, were the whole to illustrate the concept that is illustrated by one of its parts. Any part that replicates an idea or ideas already illustrated by another part of the artistic illustration is conceptually redundant, while any part that does not does not reproduce the conceptual illustration does not nullify the conceptual illustration evidenced in the part of the artwork in which it is realized.

3. Singularity and plurality; figuration and abstraction

While Bochner did a series of drawings in illustrating Wittgenstein, any single work from that series could stand alone as an illustration without the others, so that its status as an illustration is neither enhanced by nor dependent on any other member of the series. However, that may not be the case with every kind of artistic illustration; that more than a single artwork may be required to illustrate a concept or idea can be understood by looking at the individual works that together compose a series of works bound by a single idea or cluster of related ideas, such as Roman Opalka’s number paintings, 1965/1-∞. This series consists of canvases of the same size that consist solely of white numbers that Opalka painted on them, beginning with 1 and ending with 5,607,249, with the death of the artist. Other than the first canvas, the first number of each grey canvas starts in the upper left-hand corner, with the number that follows the number at the lower right-hand corner of the previous painting.

At a later point in the production of the series, Opalka decided to add about one percent white to the original gray background of each painting, so that, at a certain stage in the sequence, the white numbers would be painted on a white background, making the individuality of each numeral difficult or impossible to discern from the blank background to which it has been applied. This is important to the philosophy of illustration since it shows that the artist working within a series can change his or her mind about an aspect of the project, or can add to or subtract from it in some way, while meaning to preserve the essential concept with which the artist began.

In addition to Opalka’s 1965/1-∞ concerning time and being in time; content as limited to the recording of a found or readymade series as art; the existential fact of history; and the inevitable conclusion of the series in death, I think the following points can be made about this complex artwork that can illustrate the concepts with which Opalka was working. Each number that appears in each painting can be understood to be a symbol that, as recorded in paint, delivers to thought and perception a thing that both figures in a series of which it is a condition of constructing and that is created as the means and object of its own documentation. Each painting filled with a list of numbers is a record created to consist of nothing more than the sequential marks of a preexistent progression and to be nothing more than a historical record that registers, through the symbols of which it consists, the place that it occupies in a particular series. As such, it constitutes a kind of reductionism fitted to the sequential, symbolic system on which it is based. And the whole series of these paintings stands as the visible statement of an apprehensible idea and intention: to define an artistic life through an output whose content excludes everything beyond systematically marking through existential acts the facts of its creation, and to situate each act of perceiving one of its paintings within a temporal sequence that is silently marked by regulated time with the same kind of numerical progression used to create the object to which that perception is directed. This quiet marking can be thought to match, as silent, the noiseless act of perceiving a painting in the series. When something ends, such as an act of painting or perception, it is no longer discriminated from things that it is not as the thing that it was. An internal lack of discrimination can be found within the ultimate white-on-white paintings at the end of Opalka’s series, paintings that can be understood to pair, as featureless facts, with the concepts and acts of painting and perception, as imageless ideas and invisible occurrences, or as the colorless conditions on which the paintings depend to be, and to be seen as, what they are.

However, that something about an artwork that in some way matches or corresponds to something independent of the work amounts to an illustration is certainly debatable, even though it is a kind of illumination that may be thought to be valuable. Thus, even if it is not clear that matching, corresponding, or presenting a comparison amounts to shedding light on something, the fact that these are matters of interest that may result from illustration can be thought to be an important philosophical and aesthetic dimension of illustration that reflection on the relation of art and illustration should take into consideration. In any case, the preceding remarks on Opalka’s work show that the relation of art and illustration is complicated and can extend beyond using a single artwork to illustrate a prior philosophical idea. As other modes or dimensions of the same work, Opalka spoke the numbers in a tape recorder as he painted them and took a picture of his face at the end of each finished painting as additional means of making objects, producing artistic delineations by using an advanced plan that used a pre-existent system, and marking the inevitable progress of time and the art history to which he was contributing.[7]

While Opalka’s 1965/1-∞ uses figurative symbols to illustrate or illuminate the ideas described, and counts as a multi-part concept-illustration, Robert Motherwell’s series of paintings, In Plato’s Cave, uses Abstract Expressionist techniques to illustrate concepts that can be found in such texts as Plato’s Meno and The Republic. Motherwell manages, with the help of the title, to make poured, brushed, and dripped paint suggest, without directly representing, the interior walls of a cave.[8] And as a percipient looks at one of the works of this series, she or he is put by Motherwell in the position occupied by the chained figures in Plato’s Republic. That is, she is “chained” by the conventions of painting and the standards of exhibition that fasten the observer to an optimum area of viewing and limits the observer to looking at the surface of the painting appearing in front of her or him and nothing else. And this fact, coupled with the two-dimensional abstract image that can be understood to be a pale reflection of the reality of the walls of a three-dimensional cave, can be thought to illustrate the imperfect knowledge of sense experience had by the denizens of the cave, rather than the true knowledge of the forms possessed by the enlightened philosopher who, through reason, sees beyond appearance to reality. In addition, the background might be thought to be a good illustration of the messy nature of the world of becoming when compared with the stable perfection of the world of being. It is also possible to think that the incomplete or broken rectangle, and its lines as lines, illustrate the relation that instances of Platonic ideas, as imperfect copies of them, have to the pristine and perfect nature of the ideas. It’s interesting to note, too, that the open rectangle would not work aesthetically if it were made into a complete rectangle. Accordingly, perhaps that part of this work could be said to illustrate a case of aesthetic adequacy or success, or even a case of aesthetic perfection. If adequate, then it could be thought to be an imperfect instance of aesthetic

All reproductions of the artwork are excluded from the CC: By License.

perfection. If the latter is the case, though, and the use of the open form is thought to be perfect as it is, then there is a concrete instance of perfection in a world that, according to Plato, lacks such perfection as part of its nature. This then would amount to an illustration of the incorrectness of at least part of Plato’s theory. Finally, the In Plato’s Cave series of seven paintings can be thought to illustrate the concept of knowledge as recollection since, in going from one to another, one sees that they are different instances of the same thing, and knowing that depends on memory. Although Wartenberg does not consider such works, it’s interesting to think about the notion of illustration here and its relation both to abstract painting and to abstract concepts.

4. The relation of intention to illustration, interpretation, and time

The standard case of concept-based, or text-based, illustration of the kind that Wartenberg considers is that the concept or text exists prior to the artwork that illustrates it, but the question of the non-standard relation of intention to illustration can also be raised. Can the relation of intention to illustration be revealed in the process of creating the illustration, so that the thing being created is determined to be an illustration in the process of, or even after the fact of, its creation? What is the relation of illustration to conscious and unconscious thought here? That Wartenberg is willing to recognize both that there are cases of non-standard relations of intention to illustration and that what an artwork can be understood to illustrate may come with or after the art that is providing the illustration suggests that additional work is required to explain the relations of these things to one another.

Any of the larger, late lily-pond paintings by Claude Monet provides an example of an artwork that illustrates something that the artist may not have consciously intended but that is later revealed to be supported by the work. The late paintings by Monet are not like traditional paintings that present a single, stable image that can largely be seen and comprehended from a single position in space. Rather, in a large, late lily-pond painting, properties of the work so link with perception and agency that a single, stable substance dissolves into a sequence of events with no determined order. Certain properties of these works, including size and techniques of paint handling, present a menu of options for visual data to change with observation and function in relation to conscious choices in ways that give the work an observer-relative performative dimension. Changing angles and distances of seeing results in different patterns of visual organization that, as a result of the observational positions dictated by choices, convert the painting from a single, stable image into a series of shifting data coordinated with an observer-determined sequence of events of perception. That is, they convert being into becoming. In these late works, Monet replaces cross-temporal sameness in painting with changing clusters of sense data that are islands in a sea of change and dispersed in time according to choices that are dictated by no advance directive to assume a particular order. The design of these works, to enable a set of dynamic patterns to emerge from observer choices undirected by a prior script, gives them a conceptual dimension that presupposes their perceptual properties and prefigures a kind of Performance art in which the observer is the performer, not the artist or someone else acting on his or her behalf. In addition, the performance is not marked off as being a work of art in the way in which the performances of Performance art typically are—think of Chris Burden’s Shoot or Bed—but consists of a series of action-determined visual events that are designed to be elicited by the painting as the condition of revealing its performative dimension. The relation of a painting here to action is somewhat similar to Werner Heisenberg’s observation that, in speaking of the relation of man and nature in science, “what we observe is not nature in itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning.”[9] What we observe in late Monet is not an independent painting found in passive perception, but a means of realizing a set of experiences that are connected to a series of visually informed and informing deliberate actions.

What Monet’s intentions were in making these wonderful paintings may not be known, but on the assumption that he was not consciously trying to replace a substantial with a performative object, this raises the question of the possibility of unconscious intentions and their realization in a work of art to which the intentions are subsequently and analytically linked. That is, if a work supports the interpretation that its relation to intention allows, then can we say that the artist realized in a work of art an intention of which he or she was unaware? I see no logical obstacle to thinking that an artist can articulate an idea by creating a work in which unvoiced intention figures in its creation, so that the intention is revealed in the visible residue of an artistic action, rather than being publicized in words or even brought to consciousness in the mind of the artist. Monet must have intended to paint a particular way to bring about a painting with a certain look and structure, but the paintings so realized may have properties that he did not consciously intend, yet that are consistent with illustrating the concept of an observer-dependent performative object, which I maintain that the lily-pond paintings reveal to be possible. In any case, if Monet’s late work can be seen to exemplify the notion of an observer-based performative object, as I have maintained, and he neither consciously nor unconsciously intended to produce such works, then these paintings would count as theory-based illustrations in Wartenberg’s sense, since I am using them to illustrate my theoretical thinking about them. In fact, Wartenberg’s notion of a theory-based intention gives us a means of accommodating unconscious intentions through recognizing their relation to a theory that the artworks to which they are supposed to be connected are used to illustrate.

5. Technique-based and history-based illustrations

A late lily-pond painting by Monet is an example of what I think of as a technique-based illustration. A work of art that is a technique-based illustration can be thought to answer a ‘how’ question, such as, how can a painting convert someone attending to it from being a passive recipient of settled information to one who is an active participant in the construction of a work as process? It can also be understood to be the answer to a ‘what’ question, such as, what would one have to do to change a painting from being a single stable substance into a shifting set of visual information linked to a series of perceptual events? The techniques required of and involved in bringing about an artwork as an answer to a how or what question gives this kind of illustration its meaning. The how and what questions asked show how a technique-based illustration can also be understood to be a problem-based illustration. Monet’s late paintings can be understood to solve the problem of how to extend Impressionism, and past painting in general, into undiscovered areas in the ways that I have suggested are appropriate to their nature and identity. Techniques suitable to answering a how or what question are techniques that fit solving the problem to which a how or what question pertains. Because the solution of an artistic problem is realized through understanding and confronting the problem with concepts, a technique-based illustration can be understood to be a kind of concept-based illustration that extends Wartenberg’s concept in ways that the history of art would seem to demand. And because a technique or techniques is suited to confronting an issue, it is apt to use the term ‘technique-based’ to apply to an artwork that illustrates how to solve one or more artistic problems. Any problem that a technique-based artwork can be understood to solve arises in relation to things that come before it in art history and to which the solution in some way reflects a relation. For this reason, a technique-based illustration can also be understood to be a history-based illustration. Monet, for instance, may have wondered how to extend Impressionism in ways that no one, including himself, had yet imagined. This positions the late works of Monet’s Impressionism in relation to the earlier works of Impressionism, and so in relation to history.

It is a feature of art history that past works of art can be reinterpreted in relation to later works of art, including in relation to works to which the past works may be only peripherally related. Monet’s late lily-pond paintings are examples of works that can be reinterpreted in ways that are consistent with works that emerged in subsequent art history. Looking at the relation of later work—Abstract Expressionism and Performance art, in this case—to earlier work can change the way we think about the past in virtue of understanding its relation to a later present. Later work might be thought to reveal what an earlier work illustrates by providing a perspective on a concept that may not have been voiced or anticipated by the artist responsible for the illustration. This indicates that art does not stand still, in the past any more than in the future. Because of this, a difference between the conceptual and the historical relation of an illustration to the idea illustrated has to be recognized. History is set in time as a particular relation of different events. This relation does not change; nothing can happen that would place Abstract Expressionism earlier in time than Impressionism. However, this immutable relation of things does not constrain the possibility and nature of conceptual and aesthetic relations that can come to hold between things that occupy different historical areas. Certain aspects of the vocabulary of Conceptual and Performance art can come to be applied to certain works that appeared before the genesis of either kind of art, as I think can be the case with Monet’s late works. Thinking of Turner in relation to Rothko, and Malevich in relation to Reinhardt, Ryman, and Minimal art, for instance, shows that works of the past can acquire properties in relation to the future, and illustrate that the future can change the past in ways that are consistent with understanding the relation of later to earlier artistic efforts.[10]

6. Modernist art as philosophy

Chapter Six of Thoughtful Images is a very stimulating and significant consideration of modernist art as philosophy. The matter of the greatest interest and importance in this section of the book is the idea that it is possible to consider some kinds of art as means of doing philosophy. Wartenberg says that this was done by the Abstract Expressionists, when they revealed, as maintained by the critic Clement Greenberg, their understanding of flatness to be what is essential to painting.[11] Is this view of Greenberg’s correct? What is the effect on Abstract Expressionism as illustrated philosophy if it is wrong? These questions suggest that the consideration of art as philosophy requires the further consideration of the relation of philosophical art to its interpretation by the artists who made it, art critics and historians, philosophers, or anyone else. What is the relation of Modernism and philosophy if such protagonists of Modernism as Greenberg and Barnett Newman get at least some of the thoughts supporting Modernist painting wrong? For instance, the quote of Barnett Newman’s that the Abstract Expressionists “began, so to speak, from scratch, as if painting were not only dead but had never existed” sounds naïve,[12] since Kandinsky (no one knew about Hilma af Klint until recently), Mondrian, and Malevich had already left depiction behind, and references to the world beyond the painting were especially minimized by the work of the latter two artists. In fact, in certain important respects, Newman continues the geometric abstraction that Mondrian and Malevich had started, since in his mature work he seeks to determine how to continue Mondrian’s concern with flatness and the destruction of volume and succeeds in illustrating that what works vertically with lines and rectangles will not work horizontally with the same means. And someone could maintain that “a pure world of unorganized shapes and forms, or color relations, a world of sensation”[13] was precisely what resulted from his working practice, whatever its etiology, and however he thought about it personally. Thinking of artworks as cultural constructions that merely register or respond to external events is unduly parochial. Art has a history to which its works respond and further develop. Important artworks that extend that history through means sufficient to that development react to its history as much as novel proofs and theories respond to the histories of science and mathematics. Artists can sometimes understand their work better than anyone else, but this is not always the case, nor does it have to be. And of course, the misreading by an artist of his or her own intentions can affect thinking about the art that is thought to illustrate or at least conform to those intentions.

I think that both Newman and Rothko felt the need to link their work to something beyond it to justify it, thinking perhaps that good design—or significant form that caused aesthetic emotion—was not enough. But the question is, why is it not enough? Abstract Expressionism counts not just as concept-based illustrations, as Wartenberg maintains,[14] but as a technique-based means of illustration in which painting is reduced to its essentials by determining a set of visible relations divorced from pictorial reference. As such an illustration, it shows how to make art more pure, significant, and autonomous. And in illustrating these things in the techniques that are relevant to that illumination, it builds on prior work and so qualifies as a history-based illustration that reflects the contribution to its pictorial advances of the achievements of earlier periods. Wartenberg quotes the best-known remark of Greenberg: “The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence.”[15] As Wartenberg indicates, this meant that, for Greenberg, “painting had to focus on the nature of painting itself without importing any “alien” content, which meant that Modernist paintings had to “create works that had no content other than painting itself.”[16] I think that this approach to thinking about Rothko and Newman makes more sense than tying what they were doing to external events or to dramatic aspects of the human condition.

In any case, Wartenberg is right when, in talking about Jackson Pollock, he states that “every inch of the canvas became equally significant,”[17] and that Pollock eliminated the central focus that most paintings had to that time. There is no focal point in Pollock’s mature drip paintings; there is a breakdown of the distinction between figure and ground, to the extent to which they can be distinguished, and they take on equal visual and compositional value. One way to think about this is that some later works by Pollock consist of an integration of positive and negative space that may be seen to dispense with both as traditionally conceived and commonly related, resulting in a field of interacting elements that formed its own visual universe, not directed to or concerned with anything beyond itself. However, this is just work that extends the concerns of earlier artists and originated with Turner in the nineteenth century.

As Wartenberg notes, I think that Greenberg’s labelling of Manet as the first Modernist is wrong, that Turner was much more radical years before Manet, and that Turner’s work is more important to Modernism and to the evolution of twentieth-century art in general than Manet’s. Turner’s painting has a flattening effect on Renaissance space, which he achieves in a way that focuses on thin paint, translucency, and the blending of different spaces that, in softening precise edges, makes one question the reality of durable boundaries as it forces the viewer to reexamine notions about depiction in relation to what and how something is visibly portrayed. Manet, on the other hand, focuses on impasto and the physicality of paint as a material object; pictured objects are much easier to identify in Manet than in Turner. Greenberg just privileges one over the other without arguing why one is more important than the other. Both Manet and Turner draw attention to paint in relation to surface and image, but do so in different ways. I think that Turner is the more radical of the two because of the effect that his integration of positive and negative space, and the blurring of the distinction between them, has on the evolution of organic abstraction and even on Minimalism and Conceptualism as they extend investigations into the fundamental conditions of making and apprehending works of art, and so extend the notion of reflexive investigations beyond painting to art itself. Since this is the case, the suspicion is that Greenberg simply preferred Manet’s paintings to those of Turner, which makes Greenberg seem more like the “critic of taste” that Joseph Kosuth has said he was, rather than being someone who articulates impartially what he took to be central to Modernism and its historical development.[18]

Wartenberg says that Modernist painters were creating concept-based illustrations of the flatness that Greenbergian Modernism takes to be essential and exclusive to painting. A problem here is that the essence of painting as painting includes the use of paint, in various ways, to draw attention to the nature and existence of that medium that, while having been applied in some way to a flat surface, draws attention through the nature of that application to the paint and away from the surface. Thus, the effect of certain techniques of painting, and perhaps Pollock’s drips and squeezed-from-the-tube impasto in particular, is to focus attention on paint as paint, rather than on flatness as flatness. As a result, these techniques can be taken collectively to be a different Modernist means of showing something else to be essential to painting—not perspective, images, or pictorial reference, but paint. Then the reflexivity that is characteristic of Modernism is shown in another way by using paint as the essence of painting to illustrate characteristics of that essence that are revealed in that use.

All reproductions of the artwork are excluded from the CC: By License.

Additional problems for Greenbergian Modernism’s focus on flatness is that flatness is found in the stage on which drama performs; it seems clear that it would be hard to perform most plays on an undulating surface. It is also shared by the screen in cinema and the paper on which photographs are developed. In fact, since photographic surfaces are flat, and one can photograph a sheet of white paper so that the photograph, while still recording an object from the external world, presents it as a flat phenomenal field that coincides physically with the surface that it occupies, this might be taken as the logical conclusion of Greenbergian Modernism as applied to photography, as much as the monochrome can be viewed as such in painting. It is also not clear how flatness is a method rather than possibly a condition of painting. And, as paint can be applied to a warped or irregular surface, flatness is not an essential condition of painting. In addition, the stability through time, perception, and action of the physics of matter on which the flatness prized by Greenberg depends is no less an essential feature of painting than the flatness that requires that physical stability for paintings to be executed and continuously perceived.

Given the contest between the preceding points and the fact that Wartenberg says that “the attempt to provide a definition of painting that would lay bare its essential nature was a mistake,”[19] one wonders about the preservation of Modernism as a philosophical illustration, if it is predicated on a false foundation. More particularly, how is an illustration that rests on a questionable framework to be characterized? Can Modernist art as philosophy be maintained if some of the points on which it rests are reexamined and replaced with others that make the philosophical characterization of Modernism acceptable? Should we say that competing illustrations of Modernist philosophy should be recognized and then separated into those that are true and those that are false? Or, since all art depends on subjective interpretation and evaluation, should conflicting illuminations of some aspect of its history be sorted into those that are better and those that are worse? How does any incorrectness in that philosophy affect the aesthetic value that such works might be thought to have in virtue of their being illustrations of Modernist painting? If some equality of viewpoints is recognized, then perhaps Modernism as philosophy could be retained within a perspective in which different phenomena that are taken to undergird the same system of thought are thought to be equal sources of Modernist illustration.

7. Cézanne: Pictorial realism and idealism

In this section I consider Wartenberg’s notion of certain painters philosophizing in paint, or illustrating concepts that can be understood to be philosophical in addition to artistic, in relation to the work of Paul Cézanne. Cézanne’s painting, The Basket of Apples, is a technique-based illustration that shows how to get beyond the “reflective realism” of the mirror to approach realism and idealism within the same work by treating recognizable images and data in different ways. It solves an artistic problem by showing how realism in painting can be valid after photography, and does so in a way that involves the mind and perception of the viewer, thus adding ideal dimensions to a figurative work.[20] This work is also a history-based illustration, in building on earlier models of realism as it reveals how to produce a version of realism in paint that is difficult or impossible to do in another medium such as photography or film. If painting can do something that other media cannot, then this illustrates a kind of realism that speaks to a possibility that can only be actualized, as a dimension of reality, in a particular way in a particular medium, and the concept of realism is extended accordingly. This kind of realism involves a kind of idealism too, in depending on mind and perception for the work to illustrate what its technique of expression is enlisted to do. Idealism here is also linked to the knowledge of history and the conscious attribution of value since part of the importance of what Cézanne did lies in when he did it.

This work by Cézanne illustrates— in illuminating, making clear, or elucidating—several artistic ideas. These ideas, as revealed to mind, are ideal and as abstract as those entertained by philosophy. One is enlightened by understanding the ideas that the painting illustrates as a technique-based work. For instance, it illustrates the connection that it has, through the fragmentation of objects in space, to the Analytic Cubism that will follow it about fifteen years later. The front lines of the top edge of the table on the left of the tablecloth do not match the same edge to the right of the cloth. This is also true for the lines representing the bottom front edge of the table. These lines “stairstep” up from left to right and down from right to left. This is also the case for the line representing the top edge of the back of the table. It goes up in steps from left to right and down in the same way from right to left. Fragmentation is a concept whose use and understanding depend on the mind, making its use in the work ideal as it yet pertains to the analysis of common objects. It is illustrated by the front and back of the table. Although Cézanne’s treatment of the table lines in this painting can be understood to be a case of visual hyperbole, he noted in his studies of perception that if a straight line, such as a table edge, is broken by an opaque object, such as a tablecloth, that the different parts of the line are slightly separated so that it is not actually seen as straight. Rather, the mind-brain puts them together. This relation between eyes and brain can be understood to be relevant in a different way to the realism and idealism that this work can be understood to address. According to the art historian Katherine Kuh, break-up is the core of modern art,[21 and this work illustrates how one aspect of that development, the geometric abstraction that will be developed soon in different ways by Mondrian and Malevich, gets its start with Cézanne.

Other things illustrated by the painting include the following: If you divide the wine bottle vertically at the right edge of the reflection, you will see that it is painted as if from two different perspectives. Representing the same thing from different perspectives characterizes the simultaneity of Analytic Cubism. That is an abstract idea whose meaning and value in art depend on mind. The flat surfaces on the faces of some of the apples represent the shift away from a Renaissance perspective to prefigure an aspect of the flattening of space in Analytic Cubism and anticipate its development in the surface flatness of Greenbergian Modernism. Finally, the lower red line of the tablecloth, in appearing to be detached from the cloth itself, anticipates the liberation of line or its release from the service of representation, to be investigated on its own given its intrinsic nature. All of these things are abstract artistic ideas that involve both thought and perception as kinds of ideal event that are illustrated by the Cézanne and suggest that the illustration through art of abstract ideas is as worthy of reflective attention as the abstract ideas of philosophy.

Fragmentation and the presence of realism and idealism within the same work are important advances in art that are realized in novel ways by Cézanne. Another is the use of paint that, although figuring in or as a figurative space, is less representational than pictorial. As such, it figures as a feature of an aesthetic whole in which it is bound by relations to other features to which it pictorially equivalent. By ‘pictorial equivalence,’ I mean that parts of a painting are equal terms in an apprehensible relation connecting them. For instance, a brushstroke of unnatural green in the sky of the Monte Sainte-Victoire landscape reproduced is one term of a spatial relation that connects it visually with a corresponding patch of paint in the ground of the landscape. And if the sky as an area is put on equal pictorial footing to the ground as an area, then sky and ground form terms in a dyadic spatial relation that unites them as paired constituents of a larger visual field. The spatial relation of the brushstrokes or the areas of the painting cited is one that can be described either by saying that one is above or below the other. The spatial relations of things in a painting can also be temporally related to one another, either by being perceived at the same time at which they form terms of a spatial relation or by one being perceived before or after the other.

The idea of equivalence in pictorial equivalence as defined is that each term is equally a term of the relation and there would be no relation without them. This idea of pictorial equivalence is nevertheless consistent with divergent aesthetic value, in that one term may be thought to contribute aesthetically more than another to the relation of which each is equally a term. Because pictorial equivalence depends on its recognition to function as pictorial, and because recognition depends on mind in being a mental event, pictorial equivalence is ideal. At the same time though, it can be understood to be a kind of aesthetic realism in illustrating objectively a prior pictorial possibility. This idea of pictorial equivalence demonstrated in a technique-based illustration has a forward-looking historical dimension in which the immensity of its influence on subsequent work is palpable. And the historical fact of its influence on the subsequent work of geometric abstraction gives it an additional dimension of both realism and idealism. It is real in the way in which it factually resides in art history, and it is ideal in the way that it continues to function fluidly, not immutably, in art history and interpretation in virtue of the knowledge of the work that is sustained over time by mind.

8. Art history and illustration

Finally, it should be recognized that works of art, understood as technique-based illustrations, fit into art history as history-based illustrations that constitute, as they illuminate, the course of development of that history, and they figure as such illustrations in the ways in which the history that they combine to construct can be interpreted, evaluated, and understood. Since we understand and respond to art not just through individual works of art but through the concepts and texts pertaining to them, art history can be understood to be a kind of text. And taking art history as what is illuminated by the artworks through which that history is realized and maintained shows that the object of illustration can depend on, and be sustained and advanced by, a plurality of established, novel, and evolving objects. In addition, the extension of art history through an important new work can be understood to illustrate the concept on which that extension depends, so that what is illuminated by a revolutionary work is not a prior concept that is already recognized in art or philosophy but an antecedent possibility that is realized in the work through which the concept becomes comprehensible. And the concept realized through one or several works can be understood to be connected to an artistic, aesthetic, or philosophical problem whose solution the techniques employed in its production are utilized to illustrate.

A consequence of the view outlined here is that an artwork that solves an aesthetic problem is internally related as a conceptual solution to the history on which it depends and to which its technique of production illustrates how then to contribute. This presents no philosophical difficulty, but merely shows how artworks of novel importance are conceptually connected, as illustrations, to the art history that they help to advance.

It has been the primary purpose of this commentary not to be critical of the solid foundation of art and illustration laid by Thomas Wartenberg, but to suggest ways in which the philosophy of art and illustration might proceed in building on what Thoughtful Images has thoughtfully begun.

Jeffrey Strayer

strayerj@pfw.edu

Jeffrey Strayer is a philosopher and artist. Strayer is the author of Subjects and Objects: Art, Essentialism, and Abstraction, Brill (2007) and Haecceities: Essentialism, Identity, and Abstraction, Brill (2017). Recent publications include “Planarity, Pictorial Space, and Abstraction,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Image Studies, Purgar, Krešimir (ed.), Palgrave (2021) and “IrDaEdNiTcIaTlY,” in Where is Art? Space, Time, and Location in Contemporary Art, Simone Douglas, Adam Geczy, and Sean Lowry (eds.), Routledge (2022). Strayer’s research in philosophy is concentrated in philosophy of art, with attention given to issues in metaphysics, epistemology, and value theory that are relevant to that focus. Strayer’s Haecceities series of artwork uses language distributed in space and time that is directed to, and uses, consciousness and agency to explore identity and difference and their relations, both to one another and to the objects, acts, and thoughts on which they depend. Work from that series was most recently exhibited as part of a group exhibition in project8 gallery in Melbourne. His work in art and philosophy is an interactive and mutually supportive exploration of fundamental issues relevant to each. See www.JeffreyStrayer.com. Strayer is Senior Lecturer Emeritus of Philosophy at Purdue University Fort Wayne.

Published November 25, 2023.

Cite this article: Jeffrey Strayer, “A Typology of Illustration,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Volume 21 (2023), accessed date.

End Notes

![]()

[1] Thoughtful Images, 20.

[2] Thoughtful Images, 21.

[3] Wartenberg, Thomas, Word and Image, 31, no. 3 (2015): 233-248.

[4] Popper, Karl, Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, Oxford: Clarendon Press (1979), 158-161.

[5] Email correspondence between Wartenberg and Strayer on April 5, 2022.

[6] Thoughtful Images, 21.

[7] On the possibility of considering “one work existing simultaneously in a number of different modes,” see Gary Shapiro, Earthwards: Robert Smithson and Art after Babel (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1995) 7.

[8] The use of loose, poured, and dripping paint to recall to mind something beyond the painting is at odds with how the drip, as something to be avoided, was seen for most of art history. See Arthur Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,1981), 108. And the thought that “the drip is a violation of artistic will and has no possibility of a representational function” is contradicted by these works by Motherwell and by Pat Steir’s waterfall paintings.

[9] Heisenberg, Werner, Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science (New York: Harper & Row, 1958), 58.

[10] This means that, unless the block view of the universe is correct, a different theory of time must be constructed to allow past objects to change in certain respects. I sketch such a possible view in “Time, Objects, and Properties,” an appendix to Essentialism and Its Objects: Identity and Abstraction in Language, Thought, and Action (forthcoming).

[11] “[T]he Abstract Expressionists not only undermined traditional assumptions about the nature of painting, but they did so by illustrating their understanding of what the essence of painting was, and in so doing, philosophized in paint.” (My italics.) Use of the term ‘understanding’ in the previous quote allows the view that what Abstract Expressionist took to be the essence of painting may be wrong, as Wartenberg in fact maintains to be the case when he says that their “attempt to provide a definition of painting that would lay bare its essential nature was a mistake.” That mistake though does not affect the fact that they were philosophizing in paint. After all, there are such things as mistaken philosophies, including philosophies realized in some way in art. Both quotes are on p. 152 of Thoughtful Images.

[12] Thoughtful Images, 136.

[13] Thoughtful Images, 136.

[14] Thoughtful Images, 152.

[15] Thoughtful Images, 139.

[16] Thoughtful Images, both quotes, 142.

[17] Thoughtful Images, 138.

[18] Kosuth, Joseph “Art After Philosophy,” in Conceptual Art, Meyer, Ursula, New York: E. P. Dutton (1972), 155-170, quote 159.

[19] Thoughtful Images, 152.

[20] It must be admitted that all art is ideal in depending on mind for its creation, interpretation, evaluation, and understanding. Art also depends on mind to be sustained as art. Although these things are true, I think that, in drawing attention to the relation of certain properties of the work to mind, this work by Cézanne has an ideal dimension that is more explicit than implicit.

[21] Katherine Kuh, Break-up: The Core of Modern Art (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, Ltd., 1966).