The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

An Aesthetics of Minimal Resources: Affective Ecologies at the Encounter with Environmental Ethics in Alicia Barney’s Artistic Practice

Vanessa Badagliacca

Abstract

The aim of this article is to present the early works created between 1975 and 1982 by Alicia Barney, a pioneer of environmental art in Colombia. The purpose is to highlight her ability to lead us Toward a Sustainable Attitude, the title of a conference held at the University of Venice (October 6-8, 2022), and also to claim how relevant these works remain in the current climate crisis within and beyond contemporary aesthetics debates. Taking on this approach, it will emerge that despite the attempt of the artist in some of her pieces to adopt a detached, scientific attitude in which no emotional involvement could apparently emerge, in reality she enacts an aesthetics of minimal resources that invites the spectator to look inward and think again about what a sustainable attitude can be. I would add that she activates—borrowing the expression from Carla Hustak and Natasha Myers—“‘affective ecologies’ encompassing plant, animal, and human interactions.”

Key Words

aesthetics; art; ecology; environment; minimal resources

1. Introduction: Affection, ethics, gender, and the environment in a Colombian artist’s early oeuvre

In the context of the climate crisis we have been facing in the last few decades that has reached a state of emergency, the necessity to find alternatives and sustainable attitudes for living becomes imperative. The alarming scenarios documenting the changes occurring on the planet are threatening; however, we should also think about the potential of action to find solutions and for operating changes that start with our daily actions and political decisions. Since the end of the 1960s, within the developments of grassroots movements spreading worldwide claiming labor, women’s, racial, and environmental rights, the arts have also committed to inspire solutions towards an inversion of direction, opposing the capitalist and blindly optimistic unlimited and unsustainable growth. Alicia Barney (Cali, 1952), a pioneer environmental artist from Colombia since her early pieces—such as Puente Sobre Tierra (1975), Viviendas (1975-1998), Diario Objeto (1978-1979), Yumbo (1980-2008), Río Cauca (1981-1982), and El Ecológico (1980-1981)—already proposed adopting a critical perspective towards these problems, materializing them through an aesthetics of minimal resources. Her artistic practice since then has been characterized and moved by a concern of the human impact on the environment, which resonates with ecofeminist ethics of care that grew during those same years. If we consider that an ethics of care, as Virginia Held puts it, “requires not only transformations of given domains—the legal, the economic, the political, the cultural, and so on—within a society but also a transformation and the space, to become relations between such domains,” in support of this intention of change towards a “global environmental well-being”—and I would replace the adjective ‘global’ with ‘planetary’—ecofeminists such as Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva[1] “offer an ethic of care for nature and call for a radically different kind of economic progress. They ask that development be sustainable, ecologically sound, nonpatriarchal, nonexploitative, and community oriented.[2]

It seems worthwhile here to remember that ecofeminist theories developed from the mid-1970s and onwards saw their start through the term ‘ecofeminism,’ coined by Françoise d’Eaubonne and used for the first time in her essay, “Le Féminisme ou la mort” (1974), and later works, such as ”Écologie et féminisme. Révolution ou mutation?” (1978), “stressing the link between the exploitation of the Earth and women’s rights, and delineating two far-reaching key-issues: overpopulation and the destruction of natural resources,” the first one and the other one “emphasized the value of cooperation as the basis for a social project in which the hierarchies of capitalist patriarchal formulas should be disbanded.”[3]

Environmental ethics imbued by ecofeminist thinking has seen an increase in interest in recent years, a time when we may be urged to ask ourselves: In a fast-paced society dominated by images for immediate consumption, can an aesthetics of minimal resources be noticed? Can it be useful? Not in terms of usefulness but as a possibility to provide us with a tool—and in accordance with Andrew Patrizio, when he affirms that if a shared skill among art historians exists, it surely is “the ability to pay attention.” My purpose here is to focus on some of the works of the artist Alicia Barney, who is viewed as a pioneer of environmental art in Colombia since her early works, and to analyze some of those conceived and made between the second half of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s.

Ephemeral interventions, recycled materials, and newspaper cuts in different ways all enable an intersectional perspective that claim environmental and social justice as unquestionably undivided, and that activate, as Carla Hustak and Natasha Myers affirmed,“‘affective ecologies’ encompassing plant, animal, and human interactions.”[4] It also seems important to me to state that the perspective presented here is closer to where the works are situated and consequently partial. Therefore, any mention to Colombia here is not intended to describe the social and political context of the country in a broad way, nor has the ambition to contextualize these pieces in a wider panorama such as Conceptualism in Colombia. Both approaches would need a more in-depth analysis that I hope to develop with a more expanded reading on these works in the future. However, for being the place where Alicia Barney grew up and somehow brought with her when she moved to New York for her studies, Colombia is a landmark. It is also the place where she has lived and from where she has looked with curiosity to what surrounds her, closer and further away. It has not a national connotation; it is a way to inform Barney’s “thinking from” a situated place.[5]

In this context, Barney’s work offers a “critical art contribute,” in T. J. Demos’ words, “to an imagination of ecology that addresses social divisions related to race, class, gender and geography,” and in so doing it “indicates an ecoaesthetic rethinking of politics as much as a politicization of art’s relation to the biosphere and of nature’s inextricable links to the human world of economics, technology, culture and law.”[6] Moreover, it also acknowledges that the artistic practice that Barney has developed over the years must be observed and analyzed—as curators Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta claimed on the occasion of their exhibition, “Radical Women,” in which the artist participated—with the awareness that “the vast body of work produced by Latin American women and Latina artists has been marginalized and hidden by dominant, canonical, and patriarchal art history.”[7]

2. From the personal to the political

Sustained by this theoretical frame, I will present the art pieces mentioned above, but first in way of premise, a short presentation of the artist is due. Alicia Barney is a Colombian artist living in Bogotá. She studied in New York at the College of New Rochelle (BA, 1974) and the Pratt Institute (MFA, 1977). Refusing to constrain herself and her work into categories or styles by herself and others, Barney over the decades has developed a practice that critically examines the impact of capitalism on the environment, while exploring the transformative potential of art. Her solo exhibitions include Diario-objeto (Biblioteca Central, Universidad del Valle, Cali, 1978), El ecológico (Espacio Alternativo Sara Modiano, Barranquilla, 1982), and Basurero utópico (Instituto de Visión, Bogotá, 2015). She took part in many collective exhibitions, among them El arte de la desobediencia (MAMBO, Bogotá, 2018), Radical Women (Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Brooklyn Museum, New York; Pinacoteca, São Paulo, 2017-2018), IncertezaViva, 32 Bienal São Paulo (2016), This Must Be the Place, Latin American Artists in New York: 1965-1975 (AS/COA, New York, 2021), and Periódicos de Ayer. Arte y Prensa en Latinoamérica, (MAMU, Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia, Bogotá, 2021).

Since her first piece, which dates from the time she was a student at the Pratt Institute in New York, an attempt to create through an aesthetics of minimal resources is apparent. Its name is Diario Objeto I.

It is a piece that the artist considers autobiographical, but not in the conventional sense of reproducing a narrative about herself. In a recent interview to curator and art critic Emilio Tarazona, in the context of an exhibition entitled, “Earthkeeping/Earthshaking. Art Feminisms, and Ecology,”[8] held in Lisbon at Galeria Quadrum in 2020, Barney recounts that while she was in New York, she used to collect objects that she would encounter in her way. She underscores that she would not collect just any kind of objects, but those that she considered charged with a symbolic value. Remembering those times, she mentioned:

I had everything I picked up on the floor of my apartment. Then it got to the point where I couldn’t get to my bed. I mean, it was already very difficult to move around. And then I had to assemble all these objects and at that moment I read the article of the Khipus. There I found the solution to how to frame all these objects that were already preventing me from reaching my bed.[9]

A quipu (khipu), which means knot, was a method used by the Incas and other ancient Andean cultures to keep records and communicate information using string and knots. In the absence of an alphabetic writing system, this simple and highly portable device was used to record dates, statistics, accounts, and even abstract ideas. Barney became acquainted with this ancient method and was fascinated by this nonverbal, semiotic system for being, as she said, “A mode of organizing information in a way that is completely different from the written word.”[10] Consisting of a main horizontal string or a wooden bar, with strings of different forms and colors tied to it, this technique, which also served as a tool to measure time like a calendar, proved to be the perfect solution for Barney’s diary, made not with words but with objects.

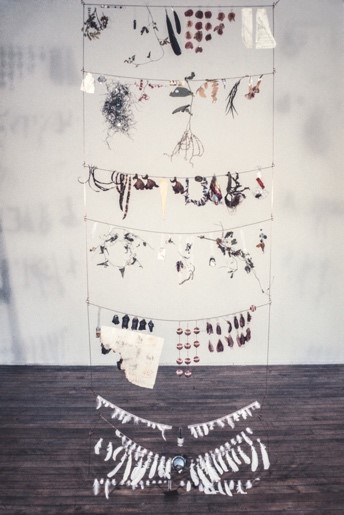

Found objects and copper, 250 cm x 90 cm (Courtesy Alicia Barney)

Besides the formal analogies between the hanging cotton strings composing the quipu and the work’s very structure also hanging from the ceiling, the reference to the calendar is particularly challenging here, especially when associated to Barney’s allusion to the objects as magical—an idea that reflects her knowledge of pop artist Claes Oldenburg’s practice and his vision and use of everyday objects in the artwork, including their gathering as a ritual and consequently envisioning the artist as a shaman. Furthermore, Diario Objeto I echoes the artist’s subsequent engagement with environmental issues in the early 1980s. For example, a selection of press cuttings draws attention to different forms of violence: normative gender identities and stereotypes. From football matches and beauty contests to the killing of animals in toreadas, to armed forces, and environmental destruction. Newspaper titles like, “The squandering of nature,” emphasize the ecological threat.

As a whole, Diario-Objeto I could also be understood as a critical examination of the residues and waste from consumer society, as affirmed by Colombian critic Miguel González in his 1982 analysis of the work. “This autobiographical work,” he wrote, “fragile and semi-ephemeral, posed to the artist alternatives that would openly place it within the urban waste, the consumer society and its rust-ridden poetics.”[11] When this piece was exhibited in Colombia in 1978, González invited the artist to write a text about it, which sounds like a manifesto and opens with the statement:

I want to form the image of an organic character in my work and develop in it an intrinsic quality, a reality in art closely related to processes of growth and decay; able to be close to an existence virtually related to the immersion of Pop Art in the idea or object of the artwork, but emphasizing the limited duration of its vital cycle.[12]

The vital cycle she refers to is particularly evident in the use of the materials she used, organic in the majority of the cases, that contributed to the ephemerality and fragility of her pieces. Meanwhile, back in Cali from New York, Barney noted the relationship between her Diario Objeto and nature, especially with the degradation of the environment that led to her shift in perspective. Remembering that phase, she recently declared: “I started to think and try not to have a sentimental narrative but something scientific to try to convince people and I failed. It was a failure.”[13] Her recognition—probably too severe, if we consider the role of art to create utopia, new imaginaries, and the possibility to make ones feel, think, and believe in a better and livable planet, but without pretension of imposition of any kind on it—may suggest a connection, in theoretical terms, with the affective turn involving theoretical and historical thinking, especially in the last decade.

For instance, in the philosophical system of Baruch Spinoza, affect remained distinct from emotions. In the Spinozian perspective, the notion of affect inhabits an unresolvable tension between mind and body, actions and passions, between the power to affect and the power to be affected. In that respect, it is through a slip of oversimplified positivity that Antonio Negri has defined affect merely as the “power to act.”[14]

The authors of this editorial, on an issue problematizing the affective turn in history, continue presenting a notion of affect that seems extremely pertinent at the moment in articulating how engaged the artistic practice of Barney increasingly became, making her one of the pioneers in environmental art in Colombia and beyond.

The notion of affect bears the connotations of bodily intensity and dynamism that energise the forces of sociality. It cannot be thought outside the complexities, reconfigurations and interarticulations of power. The semantic multiplicity of the notion of ‘affect’ emerges as particularly suggestive here: affect as social passion, as pathos, sympathy and empathy, as political suffering and trauma affected by the other, but also as unconditional and response-able openness to be affected by others—to be shaped by the contact with others.[15]

As an aside, this concept seems particularly relevant, if we think about its further development almost a decade later; in the words of Donna Haraway: “In passion and action, detachment and attachment, this is what I call cultivating response-ability; that is also collective knowing and doing, an ecology of practices. Whether we asked for it or not, the pattern is in our hands. The answer to the trust of the held out hand: think we must.”[16] If cultivating response-ability turns into an ecology of practices that interrogate our actions, we understand the political repercussions of this way of operating. Therefore, we may find pertinent the position referred to by the historians mentioned above:

The topos of affect as social passion is the relation to the other taking place within power relations; perhaps, more accurately, the taking place of affect is the displacement from the passion/affect/trauma of the other. In the global affect economy of our times, this relation seems to waver politically between the cynicism of apathy and the bureaucratic banality of compassion and unaffective sentimentalisation […].[17]

All these theoretical contributions are convoked here to underscore that Barney’s artistic practice, since her early works and continuing in her current practice, embodies in full integrity these values with environmental concerns that encompass the co-existence of human and more than human species.

3. From air to water; eco-critical art pieces

Alicia Barney’ commitment towards environmental causes is also expressed in pieces that apparently pursued a more detached and ecologically critic approach, such as her next piece.

In a different way, it would also reproduce a calendared structure, this time made from glass, a kind of material that years later she would also consider as a low-cost resource to make a piece that explicitly critiqued the industrial and capitalistic system of the country. The first version of Yumbo, the name of the homonym city where a number of multinational factories, including a Swiss one producing Eternit, were based from the 1940s onwards, was made in February 1980, a bissextile month. The piece was made up of 29 boxes in glass measuring 20 x 20 x 20 cm each. Every day during that month, Barney would leave each box open in the industrial area of Yumbo, a northern part of the city of Cali. The boxes were sealed one per day, thus collecting the visible pollution particles in that area. The second version was carried out in 2008 in the same way and under the same conditions.

A recent analysis of this piece by art historian Gina McDaniel Tarver provides a relevant contribution to our understanding of Barney’s work and affective engagement toward the topic she presents:

Taking the reduction of pollution as the ultimate goal of Yumbo, the work is a failure, as emphasized by its recreation twenty-eight years later. Its making visible is insufficient. The failure of Yumbo in part derives from, or at least connects to, our society’s enduring Enlightenment-era belief in science and in human’s separation from and ability to control the natural world. Barney had been hopeful that, giving an audience clear empirical evidence, she might induce action. An activist at heart, Barney declared, “art should transform reality, not reproduce it” (GONZALEZ, 1979, p. 12).[18]

The structure of the piece reminds one also of Hans Haacke’s early work, Condensation Cube (1963-1965), which exemplified his interest in such basic physical processes as the evaporation and condensation of water. Such work can be framed within the increasing influence of cybernetics on contemporary art across Europe and the Americas towards the end of the 1960s. The term ‘cybernetics’ was first employed by Norbert Wiener, in his influential book Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in Animal and Machine (1948). The text addresses the science of machines and how information is translated into control and regulation within a given system, whether it be mechanical, biological, cognitive, or social. Years later, Barney believed—at the time when she conceived Yumbo—that a rational, cold approach in her artistic practice would provide a useful response for environmental action, and she repeated the attempt with another piece that this time would highlight the problem of urban and industrial pollution not by analyzing the air but the water.[19]

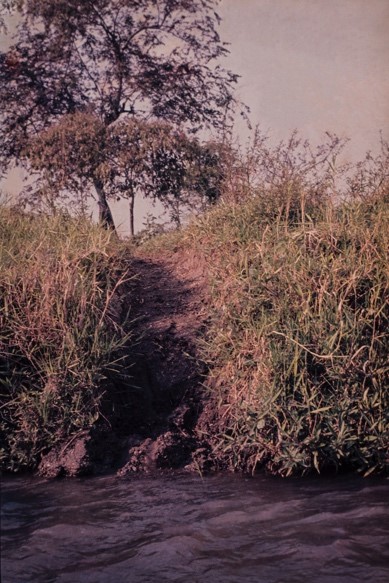

Her second eco-artwork, as the title refers, was focused on the waters of a river, Río Cauca (1981-1982), a piece that challenged and problematized systems of social control, capitalism, colonialism, and extractivism. The river Cauca flows 600 miles, south to north. It runs through the nation’s most productive agricultural area, the Valle del Cauca (Cauca Valley), dominated by the sugar cane industry. Affected by the rapid urban population growth that accompanied industrialization, the chemicals in the river near Yumbo corresponded to the growth of new, mostly multinational industries.

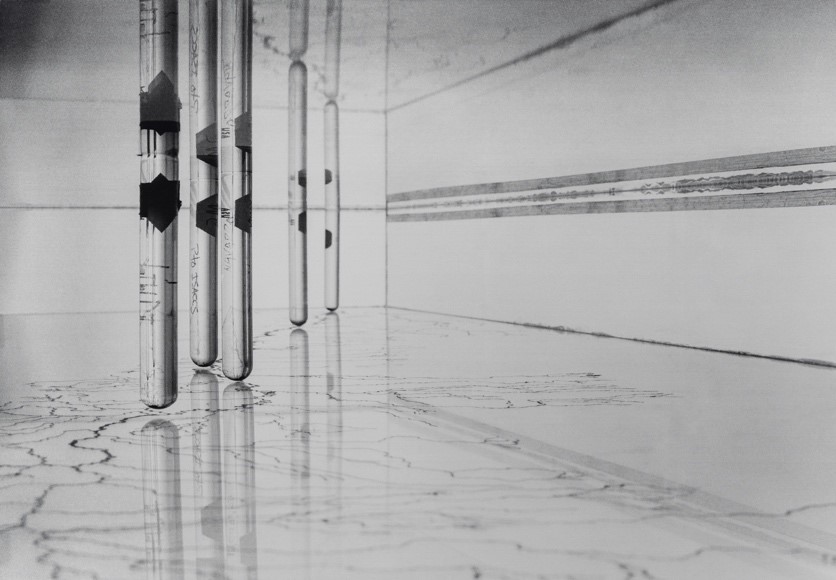

Photograph: Mauricio Zumaran (Courtesy Alicia Barney)

For Río Cauca, Barney, paddling in a canoe, collected water from the river (those being material proofs of the contamination of waters), first from its source above Popayán, where she filled five large jugs with water. Barney recruited the biologist Roberto Díaz from the Universidad Nacional in Palmira to travel with her to five river locations within the department of the Valle del Cauca, from south to north.

With the scientist, Barney went to:

-

La Balsa, where the river enters the department;

-

Puerto Navarro, near a major sewage dump in south Cali;

-

Puerto Isaacs at Yumbo;

-

Zambrano, downstream from a sugar processing plant; and

-

Gutiérrez, where the river leaves the department.

For each place, Barney took photos at the north, east, south, and west as a visual, geo-referenced record. The goal of her investigation was to alter mindsets, enforcing symbolic changes that might result in action. To display her results, she built three shallow acrylic tanks, each one for samples taken from the surface, mid-depth, and bottom of the river. Each tank was lined with a hydrological map of the river, and test tubes containing soil samples were suspended above the points on the map that represented sampling locations.

Photograph by Guillermo Franco. (Courtesy Alicia Barney)

Clearly labeled photographs illustrating the sampling process hung on the walls near the tanks alongside the scientific analyses, and large containers used to collect the source water sat nearby. Overall, the display suggested an investigative process similar to those that academic activists were increasingly employing to expose ecological devastation.

In the words of Gina McDaniel Tarver:

With Río Cauca, Barney’s strategy was to make corruption visible, not by overwhelming the viewer with the river’s abject state but by contrasting the contaminants with the beauty of source water within an immaculate and orderly display in order to prompt rational reflection and action. The pollution is carefully contained in the test tubes, held in suspension within the source water. Río Cauca seems to be a promise that the problem can be controlled. Barney stills the ongoing process in order to hold the various elements in tension, as at a crucial moment of potentiality and reflection.

Tarver goes on pondering the geographical implications of Barney’s work:

A river map is a practical absurdity—it charts a liquid that is in constant flux, never the same twice, as Heraclitus wrote. In Barney’s installation, there is the map, the same three times, but the river, she simultaneously reveals, is not consistently the same and has hidden depths: we can only know it partially, in bits, as an abstraction, through the magic of the map.[20]

While she was working on Río Cauca, Barney admitted in a recent interview, “I still had hopes that people would react in time.”[21] On the south end of the Cauca in 1981, Barney exhibited a river that was threatened by pollution, but crystallized in a moment of tension and possibility. She believed that rationally revealing the problem might lead to a solution. As Tarazona poetically pointed out, the river becomes “a metaphor of time and the irreversible damage that, as an accumulation of human activity, it drags and also overflows.”[22] At this time of climate catastrophe, this piece of eco-art today challenges viewers to ask what it can achieve and how it can accomplish it.[23]

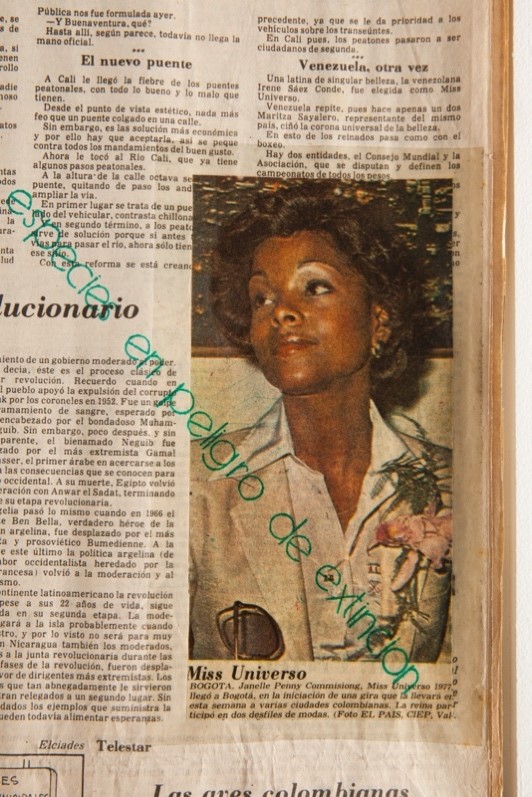

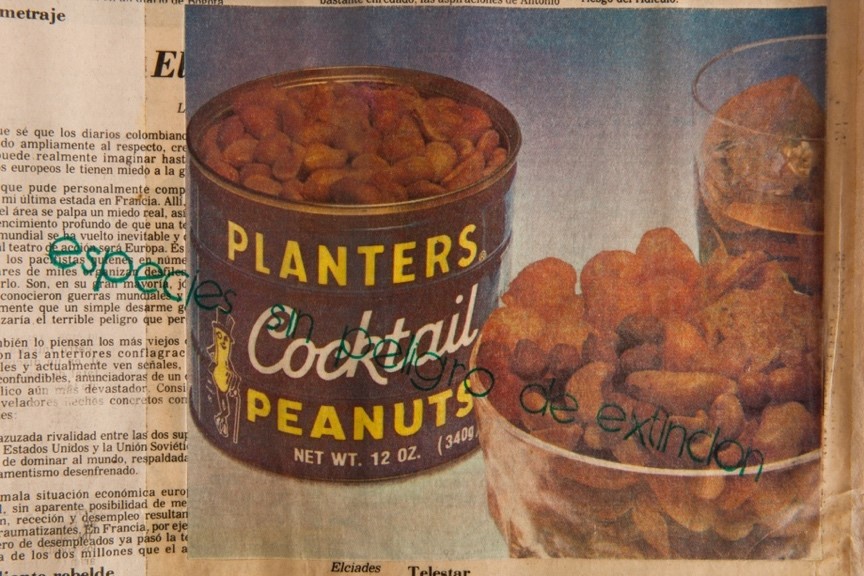

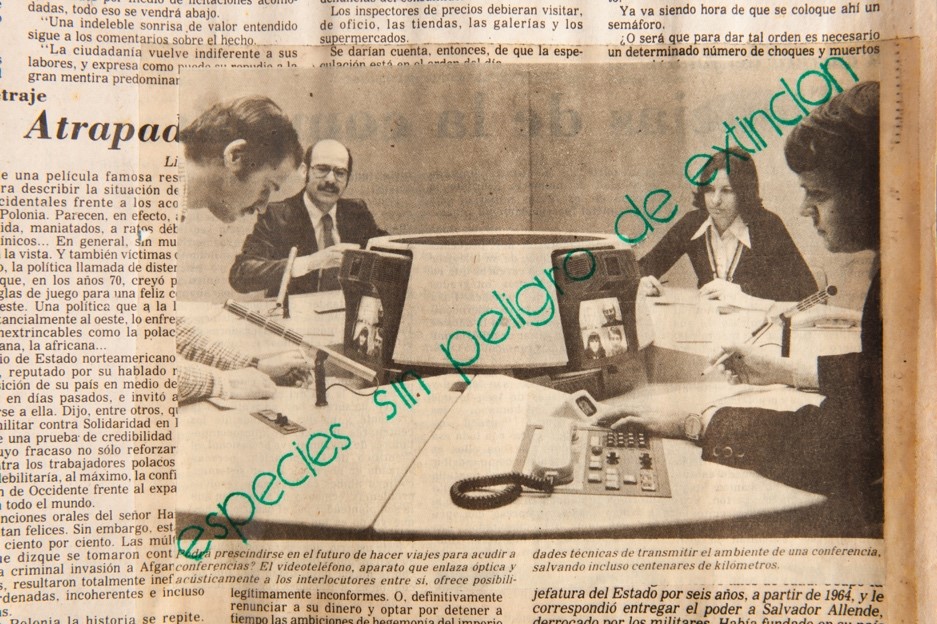

In that same period, Barney also released another, more explicit eco-art piece, titled El Ecológico, an intervention piece composed of ten newspapers. The procedure to prepare each of them implied the printing of three different stamps. The first one erases the original name of the newspaper; the second one substitutes the title of the newspaper with the new number, which also gives the name to her piece; the third alternates two opposite messages, depending on the image it refers to. The attempt was to create awareness about the supposed permanence of some situations and the threat of disappearance of others in the future. In 2020, this piece participated in the exhibition in Lisbon mentioned earlier through some prints in the form of postcards that visitors could take with them. On that occasion, Barney was shocked by the fact that this piece remains timely—sadly nothing has improved since then.[24]

Barney appropriated Colombian newspapers and turned them into an artist’s publication, entitled El Ecológico. By selectively marking a series of newspapers with the stamps “en peligro de extinción” (in danger of extinction) or “sin peligro de extinción” (not in danger of extinction), she emphasizes how the environment and nonhuman life, indigenous minorities, and non-Western values are threatened by extinction, whereas gender violence, racism, Western beauty stereotypes, and the transformation of labor by multinationals operating on a global scale endure.

Measure for each newspaper 2 x 39 x 62 cm. (Courtesy Alicia Barney)

Interestingly, by alerting the viewer on these different issues (curiously enough, El Espectador [The Spectator] is the name of one of the newspapers used by the artist), Barney traces connecting lines, ultimately showing that the different forms of oppression and violence pointed out in El Ecológico structure each other, and that a dangerous idea of economic development has taken root. El Ecológico also proves that the appropriation and transformation of everyday objects and practices can be an effective critical tool for articulating a political positioning while emphasizing a (feminist) connection between the personal and the political. Applying this kind of label, in danger or not in danger of extinction, not only towards the environment and the alert to the destruction of the planet but mostly to social realities of the present, the critique she provokes is also ironic and even paradoxical—and yet adopts an aesthetics of minimal resources.

4. On the earth, upon trees

Like many women eco-artists, Alicia Barney also intentionally rejected massive, forceful, and highly visible approaches to the environment, seeing machismo and Western civilization’s attempts to control nature in the aggressive reshaping of the land.

As Tarver poignantly noted:

Their formal decisions furthermore draw attention to the intangibility and mutability of many of the most important aspects of our ecosystems. Minimal or limited visuality—relative invisibility—can be both a metaphor for those aspects of material reality that we either cannot or do not see, because of our conceptual limitations and a catalyst for moving beyond an emphasis on the visual and strictly empirically-grounded approaches to understanding, to a consideration of other forms of experience and knowledge.[25]

In this regard, and going backwards to Barney’s seminal pieces that sustain an aesthetics of minimal resources, as my intervention aims to highlight, I will conclude by presenting two more pieces. Her first work, and first environmental art piece, was an ephemeral intervention, entitled Puente sobre tierra (1975), a series of six photographs of an action that took place in the countryside in Valle del Cauca, in the vicinity of Cali. While a bridge is generally a structure connecting the two margins of a water flow, here the bridge the artist made by with earth is an almost imperceptible footpath that links two aquatic poles. This operation, which could allow water creatures to transit between one and the other extreme of this temporary construction, significantly de-centers the human and, at the same time, because of its small and unpretentious scale, defines itself as a non-monumental piece. “The intention—she asserts—was that no one would see it, but for some reason I took pictures of it.”[26]

Considered by Barney her “most feminist work,”[27] Puente sobre tierra overtly goes against the grain of land art practices of North American male artists, and the large scale of many of their interventions, of which Spiral Jetty (1970) by Robert Smithson is perhaps the most well-known example.

Moved by the same intention of producing minimal intervention in the environment—able to be not evident but at the same time strong enough to stimulate questions after having been noticed—a few months later Barney made a new environmental action, called Viviendas.

It consisted of painting white vinyl doors and windows on the trunks of a group of twenty trees on the boundary between two farms in Valle del Cauca. It was an earthwork created and adapted to a specific non-urban site of about 500 meters long that no longer exists. Miguel Gonzalez’ gaze on this work somehow reflects the affective ecologies that the artist’s work seems to enable when he referred, “These are paintings on tree trunks that form a natural forest, where doors and windows are drawn, evoking a fantastic and imaginary architecture.

(Courtesy Alicia Barney)

Alicia Barney prefers to intervene in nature rather than imitate it, to paint over it instead of trying to reconstruct it.”[28]

Viviendas later in 1998 was recreated around the Art Museum of the National University, on the occasion of the exhibition, “Fragilidad” (Fragility), where Barney painted ten trees with doors and windows in white vinyl. At that time, she was reading about population and was struck by the increasing population and its effect on the planet. She decided to paint doors and windows upon the trees as a metaphor of the human imposition (through building construction) on nature. The poetic attempt of this action is evident, since contrary to the human attitude she wanted to criticize, her action would go almost unnoticed leaving a trace on the trees. In that same recent interview, she states:

The idea was that it would go unnoticed.

It seemed to me an act of rebellion towards art as an institution is the fact that anyone could find it and a work could be lived casually and accidentally and not in an intentional space where the work acquired its meaning by the place where it was. […]

I think my work has always been the opposite of monumental. My purpose is the integration with nature.[29]

Alicia Barney, Viviendas, 1998 (Courtesy Alicia Barney)

We might say that Viviendas exemplifies an idea of “nature” that is not the background, as feminist environmentalist Val Plumwood would put it, but rather a set of real presences that inhabit the environment for which were conceived.[30]

This perspective—quite evident in these early works from 1975—also implies the recognition and affirmation of a transcorporeality, as defined by Stacy Alaimo, which “emphasizing the movement across bodies reveals the interchanges and interconnections between various bodily natures.”[31] This attempt also aims to overcome dichotomies that envision nature (nature/biology/physis) as “the other” of culture, on the assumption that “culture (ideation, agency, mobility) is an inherent expression of nature (biology, matter, physis).”[32]

5. Towards a conclusion

By presenting these works by Alicia Barney, released with minimum resources and of low or almost no impact on the environment where they take place, I also tried to present all the complexity of what we may consider a truly sustainable attitude, an intersectional perspective that claims environmental and social justice as unquestionably undivided, a perspective that—borrowing the words from Patrizio, referring to art history—“shift further from egocentricity to ecocentricity,” [33] and yet goes beyond it. In fact, if on the one hand this statement claims for a necessary expansion in the discipline, it also displays its potentials and limits in the context of analysis presented here. The term ‘ecocentric’ was proposed by Warwick Fox to replace ‘biocentric’ ethics as being more appropriate, since the “motivation of deep ecologists depends more upon a profound sense that the earth or ecosphere is home than it does upon a sense that the earth or ecosphere is necessarily alive.”[34]

Marti Kheel evoked these variations in vocabulary choices and carefully noted that holist nature philosophy, also known as ecocentric philosophy, among whose main exponents is renowned Aldo Leopold and the above mentioned Fox, “postulates that larger entities such as ‘species,’ ‘the land,’ or the ‘the ecosystem’ should be accorded the highest value in ethical conduct toward nature.” An activist and ecofeminist theorist, founder in 1981 of the organization FAR, Feminist for Animal Rights organization, she pointed out that caring “about ‘species,’ ‘the ecosystem’ or ‘the biotic community’” stands “over and above individual beings.”[35] Her observations offer extremely relevant insights in this art historical and theoretical presentation of the early works of the Colombian artist, and particularly resonate when she affirms:

in expanding their moral allegiance to the larger “whole,” holist nature philosophers reflect a masculinist orientation that fails to incorporate care and empathy for individual other-than-human animals. I contrast the notion of care-taking for the whole of the ecosystem with direct, unmediated care for and about individual beings.[36]

In light of these theoretical contributions, we may consider how Alicia Barney’s work, since her early pieces, activates an aesthetics of minimal resources where affective ecologies encounter environmental ethics and suggest possible ways of co-existence between human and more than human beings.

Vanessa Badagliacca

vanessabadagliacca@gmail.com

Vanessa Badagliacca is Professor of History and Artistic Tradition at U-Tad | University Center for Technology and Digital Art. She received her Ph. D. in Art History in 2016 at FCSH-Universidade Nova de Lisboa with the thesis “Organic Materiality in 20th Century Art. Plants and (Human and Non-Human) Animals from Representation to Materialization.” Her academic research – interacting with her curatorial practice – explores the entanglements between plant life, environmental issues, and artistic practices, with an approach informed by the sciences, ecocriticism, and new materialisms, focusing mainly on the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America in a transnational perspective.

She has published her work in international academic journals and also dedicates herself to editing and writing for exhibitions and magazines.

In 2020 she was awarded the Terra Foundation for American Art Research Travel Grant.

This paper was written upon the participation in an interdisciplinary conference held in Venice (October 2022) and was funded by IHA of Universidade Nova de Lisboa, as the author was an integrated researcher of that Portuguese institution at the time.

Published July 13, 2024.

Cite this article: Vanessa Badagliacca, “An Aesthetics of Minimal Resources: Affective Ecologies at the Encounter with Environmental Ethics in Alicia Barney’s Artistic Practice,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 11 (2024), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] See Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva, eds., Ecofeminism (London: Zed Books, 1993).

[2] Virginia Held, The Ethics of Care. Personal, Political and Global (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 166.

[3] Veronica Perales Blanco, “Ecofeminism and Artivism: the pacific mobilizations of Women’s Pentagon Actions and Greenham Common,” in Isabel Carvalho and Vanessa Badagliacca (eds.) Leonorana n. #6, issue “Nuclear” (Porto, 2023), 21-30: 23.

[4] Carla Hustak, Natasha Myers, “Involutionary Momentum: Affective Ecologies and the Sciences of Plant/Insect Encounters,” differences 1 December 2012; 23 (3): 74-118.

[5] Donna Haraway quoting Vinciane Despret, in Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016),131.

[6] T. J. Demos, “Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology,” Third Text, 27, Issue 1, Number 120-January, Volume 27, 2013, 1-9: 2.

[7] Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985, Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta (curators), with Marcela Guerrero (Munich: Prestel Publishing, 2017), 17.

[8] “Earthkeeping/Earthshaking – Art, Feminisms and Ecology,” group exhibition at Galeria Quadrum, Lisbon, Portugal, co-curated by Giulia Lamoni and Vanessa Badagliacca, July 25-October 4, 2020. Featured artists: Alexandra do Carmo, Alicia Barney, Ana Mendieta, Bonnie Ora Sherk, Cecilia Vicuña, Clara Menéres, Emilia Nadal, Faith Wilding, Gabriela Albergaria, Gioconda Belli, Graça Pereira Coutinho, Irene Buarque, Laura Grisi, Lourdes Castro, Maren Hassinger, Maria José Oliveira, Mónica de Miranda, Rui Horta Pereira, Teresinha Soares, Uriel Orlow. https://galeriasmunicipais.pt/en/exposicoes/earthkeeping-earthshaking-art-feminisms-and-ecology/.

[9] Alicia BARNEY: En el país de las maravillas / ((n. 6)): 1/3, Nervio Óptico, 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=sewLoVlEUh0, last accessed May 30, 2023, translation by the author.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Miguel González,“Alicia Barney: el paisaje alternativo: aferrada al drama que la naturaleza provoca,” Arte en Colombia (Bogotá, Colombia), no. 19 (October 1982): 40-43. Available at https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/item/1078601#?c=&m=&s=&cv=2&xywh=-1116%2C0%2C3930%2C2199, last accessed May 30, 2023, translation by the author.

[12] Alicia Barney, “A propósito del ‘Diario – Objeto,’” 1978. Available at https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/item/1098241#?c=&m=&s=&cv=1&xywh=840%2C910%2C857%2C480, last accessed May 30, 2023, translation the author.

[13] Alicia BARNEY: En el país de las maravillas / ((n. 6)): 1/3, Nervio Óptico, 2020.

[14] Athanasiou, Hantzaroula, & Yannakopoulos (2008). “Toward a New Epistemology: The ‘Affective Turn’,”Historein, 8, 5-16: 4. Available at 10.12681/historein.33, last accessed, May 30, 2023.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, 34.

[17] Athanasiou, Hantzaroula, & Yannakopoulos (2008). “Toward a New Epistemology: The ‘Affective Turn’ ”, 5.

[18] Gina McDaniel Tarver, “Transparency and Ecocritical Art: Seeing Art History through (to) Alicia Barney’s Yumbo,” Bienal 12 Seminário Internacional, 440-446: 443.

[19] An ethics of care and a modus operandi through affective ecologies is apparent when Alicia Barney—after exhibiting and donating to the Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia in Cali the original seventeen boxes from 1980 and the twenty-nine from 2008—wrote a letter to the then director of the museum declaring that she donated the piece with the intention that it would be destined to an institution committed to re-edit the piece every twenty-five years, which we can interpret as a declared intention of the artist for monitoring the level of pollution of the air in the area of Yumbo through this artwork. In that letter, she was arguing that despite her intention, the documents she was asked to sign by the museum to seal the donation did not mention this precise request and asked for an explanation that to the present day—she referred to me in a message on January 26, 2024, with that letter attached—she has not received yet. Such an affective commitment in this environmentalist artistic practice envisions the artwork not as a final product but as a companion of the context for which and by which it was created.

[20] Gina McDaniel Tarver, “The Roar of the River Grow Even Louder.” Polluted Waters in Colombian Eco-Art, From Alicia Barney to Clemencia Echeverri, in Lisa Blackmore &Lilian Gómez (eds.), Liquid Ecologies in Latin American and Caribbean Art (New York: Routledge, 2020), 89-105.

[21] Alicia Barney, “Untitled Text,” in Art and Psychedelia: A Critical Reader, eds. Lars Bang Larsen and Caroline Woodley (Afterall and Koenig Books, forthcoming).

[22] Alicia BARNEY: En el país de las maravillas / ((n. 6)): 1/3, Cit.

[23] While I was traveling to the conference where I had the opportunity to present this research, I was reading Ursula Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. To my surprise, in the introduction, Donna Haraway refers to three bags she received as presents, one of them carrying the handcrafted letters Flore-ser, made by El Movimiento Rios Vivos Antioquia “as a means of both subsistence and resistance in the face of the immense hydroelectric project, Hidroituango, being constructed in the Cauca River basin on their lands and waters.” Donna Haraway, “receiving Three Mochilas in Colombia: Carrier Bags for Staying with the Trouble Together,” in Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (UK: Ignota, 2019), 15. I found this information an endearing coincidence and a sort of revelation, reminding us about the pertinence of Alicia Barney’s piece in the present.

[24] Mail from Alicia Barney to the author, 07/07/2020.

[25] Gina McDaniel Tarver, “Transparency and Ecocritical Art: Seeing Art History through (to) Alicia Barney’s Yumbo.”

[26] See Barney’s interview with Emilio Tarazona, “Alicia BARNEY: En el país de las maravillas / ((n. 6)): 2/3,” published in Nervio Óptico, September 2020, accessed 12 November 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5xQ5l-v5x9Q&feature=youtu.be.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Miguel González, “Alicia Barney: el paisaje alternativo: aferrada al drama que la naturaleza provoca.”

[29] Alicia BARNEY: En el país de las maravillas / ((n. 6)): 2/3.

[30] “To be defined as ‘nature’ […] is to be defined as passive, as non-agent and non-subject, as the ‘environment’ or invisible background conditions against which the ‘foreground’ achievements of reason or culture (provided typically by the white, western, male expert or entrepreneur) take place,” Val Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), 4. Afterwards, Plumwood coins the term ‘backgrounding’ to describe the treatment women and nature have received as a mechanism deeply embedded in the rationality of the economic system and in the structures of contemporary society. See Idem, 21.

[31] Stacy Alaimo, Bodily Natures, 2010, 2. Alaimo later affirms: “Trans-corporeality offers an alternative. Trans-corporeality, as a theoretical site, is where corporeal theories, environmental theories, and science studies meet and mingle in productive ways. Furthermore, the movement across3 human corporeality and nonhuman nature necessitates rich, complex modes of analysis that travel through the entangled territories of material and discursive, natural and cultural, biological and textual.” Idem, 3.

[32] Vicki Kirbi, in V. Kirby (ed.), “Forward,” What if Culture Was Nature All Along? (Edinburgh: University Press, 2017), 2017, X.

[33] Andrew Patrizio, The ecological eye. Assembling an ecocritical art history, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), 183.

[34] Warwick Fox, Toward a Transpersonal Ecology: Developing New Foundations for Environmentalism (Boston: Shambhala, 1990), 117-118, quoted by Marthi Kheel, Nature Ethics: An Ecofeminist Perspective (Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), 193.

[35] Marthi Kheel, Nature Ethics: An Ecofeminist Perspective, 2.

[36] Idem. I am thankful to Alicia Puleo’s chapter “Ecofeminismo: una alternative a la globalización androantropocéntrica”, in Daniela Rosendo, Fabio A. G. Oliveira, Priscila Carvalho and Tânia A. Khunen (org.), Ecofeminismos: fundamentos teóricos e praxis interseccionais (Rio de Janeiro: ape’ku editor, 2019), 43-62, for her inspiration of ecofeminist thinking in plural perspective and especially for bringing me back to the writings of Marti Kheel.