The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

The Temporality of the Aesthetic Appreciation of Food and Beverages

Hiroki Fxyma

Abstract

Taste and smell are gaining status in aesthetics, but theories concerning their basic appreciation are insufficient. This study aims to clarify the temporality of food and beverage appreciation. First, the temporality underlying this appreciation is classified into three categories: the time of the object, the time of the embodied cognition, and the time of the phenomenon. Next, four aspects of the time of the phenomenon are proposed: non-temporal, linear temporality, circular temporality, and point temporality. These four temporalities are not determined a priori but generated by the eater’s attention. This study provides a basis for discussing food and drink as subjects of aesthetics and addressing them as targets of aesthetic appreciation.

Key Words

aesthetics; food appreciation; taste; flavor; smell; Japanese foods

1. Food appreciation and temporality

Most people would not expect the quality of one’s experience of a slice of pizza margherita to be altered by the two ways of holding it: the V-fold style versus turnover style.[1] But on the eating experience, in terms of temporality, they offer distinct experiences. This study explores the temporality involved in food and beverage appreciation, extending beyond mere moments in the mouth to encompass non-measurable, metaphysical time.

Traditionally, time has been considered a barrier to taste and flavor achieving artistic status, as they were deemed too ephemeral.[2] However, Frank Sibley[3] and Tiziana Andina and Carola Barbero[4] refute this, arguing that even ephemeral sensations of jazz, dance, and songs can be art with their structure. Larry Shiner notes the intellectual and sensory interest of perfumes related to their complex compositional structure unfolding over time.[5] Douglas Burnham and Ole Martin Skilleås[6] refute M. W. Rowe’s[7] idea that wine lacks discernible parts in spatial, temporal, or spatiotemporal fields or lacks intellectual patterns. They argue that wine tasting, with its duration and progression, presents tangible parts and intellectual patterns, enabling critical rhetoric and aesthetic judgment. Tasting is considered a physical skill,[8] and proficiency may allow one to perceive with precision what happens in the mouth for a short period. Emily Brady emphasizes our ability to identify and localize smells and tastes, challenging the notion that ephemerality detracts from aesthetic value.[9] Further, Mădălina Diaconu suggests that the Western view of ephemerality as negative may not universally apply.[10] In fact, Japanese sake’s swift fade, known as “kire,” is prized. Thus, despite the insufficient theoretical foundation of the temporality, taste might be denied its aesthetic status because of the inappropriate application of narrow art theories that rely on one-sided values and prioritize visual and auditory modalities.

The importance of temporality in cooking is emphasized by Brillat-Savarin and Yuan Mei (袁枚, eighteenth-century Chinese poet and gastronome). Brillat-Savarin discusses three types of evaluation order in the eating process: direct, complete, and reflective sensations.[11] Yuan Mei discusses the significance of the serving order in his cookbook, Sui Yuan Shi Dan (隨園食單),[12] which covers Chinese cuisine of that era. Yuan Mei emphasizes arranging dishes from intense flavors to the milder ones, from salty to sweet, and from soupless to soupy dishes. These principles would challenge the modern practice of starting with lighter tastes before progressing to heavier ones, as often observed in sushi and other cuisines. This order extends to smells, as noted by Shiner and Kriskovets,[13] who observe patterns in the development of natural and artificial odors’ over time.

Tableware and serving methods introduce temporality to food, forming the basis for aesthetic appreciation, including composition and balance. Consider the example of a parfait. In Japan, the typical parfait follows a unidirectional (linear) temporal order, where it is eaten from top to bottom, layer by layer. Recently, Japanese specialty parfaits have evolved to include complex, multi-layered structures, incorporating diverse textures and tastes within this linear temporal framework.[14]

Figure 1. An example of Japanese multi-layered parfait. Image from photo-ac.com.

On the other hand, desserts served on flat plates (recently called ‘assiette dessert’ in Japan) lack an obvious linear temporal structure within a single plate. However, such desserts can still show temporality depending on their presentation. Assiette dessert courses offered at ambitious Japanese restaurants in recent years typically include around five dessert dishes (for example, Ensoleillé in Kyoto).[15] While each dish shares the common feature of sweet taste, variations in temperature, taste, and texture contribute to the overall course composition. Temporality has inspired many chefs to propose time-themed foods. For instance, a specialty dish at Dominique Bouchet Tokyo/Kyoto, called Caviar and Sea Urchin on Lobster Jelly[16] (Figure 2), draws inspiration from a 24-hour clock. As diners savor each piece of jelly, the clock representation gradually disappears, encouraging guests to immerse themselves in the dining experience without the constraints of time. Another example is HINEMOS (Figure 2), a collection of sake bottles named after the Japanese term for “all the time in the day.” Each bottle, labeled with different hours, is crafted with a unique flavor profile, inviting enjoyment during various times of the day. Incorporating the concept of time extends beyond avant-garde cuisine.

Figure 2. Left, Caviar and Sea Urchin on Lobster Jelly from Dominique Bouchet Tokyo/Kyoto; right, the HINEMOS series. Images provided with permission from The Westin Miyako Kyoto: Dominique Bouchet Kyoto Le RESTAURANT and HINEMOS.

The arts are typically categorized into temporal and spatial domains, leaving the question of where the eating experience fits unresolved. However, as Souriau[17] and Dewey[18] criticized this dichotomy, I believe that taste and flavor appreciation encompasses both temporal and spatial characteristics. As Cain Samuel Todd argues,[19] taste and smell exhibit temporal aspects, such as the top note/last note of perfumes, middle palate, attack, and finish of wines. Furthermore, wine and whisky aromas “spread” within the oral and nasal cavities, indicating spatial quality. Recent discussions in olfaction philosophy[20] and physiology[21] highlight temporal and spatial role in smell quality. Mădălina Diaconu points out, “the aesthetics of all the senses is a topological theory, which means that it focuses on complex spatial structures and on temporality as a factor in aesthetic value.”[22]

Examining temporality enriches food critique by revealing its aesthetic potential. By likening music as a temporal art form, food and beverages can be evaluated based on rhythm, tempo, and attack. Apart from music metaphors, there may also be the unique temporality of taste and flavor. However, exploring food temporality goes beyond analyzing wine and gourmet reviews. Reviewers would perceive time as linear, making it challenging to discuss the experience based on alternative temporalities of which they are unaware or unknown.

This paper presents a temporality classification for food experience, addressing linear bias[23] in our language and temporal concept. I will present three categories of food temporality: time of the object, cognition, and phenomenon. Then, the time of phenomenon is further classified into four aspects: non-temporal, linear, circular, and point temporality. This study is one of the endeavors that demonstrate the various aspects comprising food appreciation, providing a foundation for discussing food aesthetically.

2. Time of the object and time of cognition

This section discusses the concept of time of the object and the time of cognition. The latter basically refers to the duration from when food or drink is placed in the mouth until it is swallowed. It also encompasses the time needed for cognitive processes such as visceral sensation and learning.

2.1. Time of the object

When drinking wine or sake, we must consider the aspects of time inherent in each. These include the vintage (years), the duration from bottling to the table (days to years), the decanting time (minutes to tens of minutes), and consumption time (minutes). The flavor of wine notably changes when decanted or exposed to air.

Compared to wine, Japanese sake exhibits faster changes during storage. Sake is typically brewed during the winter months. Freshly brewed sake, known as shinshu or shiboritate, has a lively aroma, for example, apple, kiwi fruit, banana, and the like, and a clear appearance. Aging sake for half a year produces akiagari or hiyaoroshi (autumn’s sake), with a milder taste and rice-derived richness. After one year of aging, it is called koshu. The fresh aroma dissipates, and the color turns yellow or amber, but an aged aroma of nuts, caramel, dried fruits, and honey emerges.[24] Improper storage may result in off-flavors (hineka). Recent scientific analysis has elucidated the aging process.[25] While wine has an optimal period for opening,[26] sake offers distinct attributes at various stages.

Todd points out that changes within the bottle and glass encompass aesthetics, contributing to values beyond commercial considerations.[27] In addition to beverages, fruits, vegetables, and fish have their optimal seasons and provide opportunities for aesthetic appreciation. Hence, this study introduces the concept of “time of the object,” representing the inherent temporal attributes of objects.

2.2. Time of cognition

Food perception is a dynamic process. Foods undergo actions like salivation, breathing, temperature changes, mastication, and tongue agitation, resulting in “time-dependent food characteristics.”[28] These characteristics are the relationships that arise between the eater and the food through the act of eating.[29] The time of cognition includes not only physical changes in the mouth, but also cognitive processes such as learning, sensory fatigue, adaptation, and so on. Eating and tasting are active, exploratory processes, not automatic and passive. J. J. Gibson claims, “It [tasting activity] is also exploratory and stimulus-producing…. Tasting is a kind of attention, and the mouth can be said to focus on its contents.”[30]

The human respiratory system and oral structures contribute to flavor temporality. Smell perception occurs via orthonasal and retronasal routes,[31] providing temporality of top note and after flavor. Saliva dissolve food and facilitate chemical reactions, as demonstrated in whiskey’s Kentucky chew technique.[32]

Psychological factors like memory and learning influence taste qualia, shaping food choices through food aversion and preference learning.[33] While aversion and preference learning provide motivation and customs for an individual’s food choices, a highly desirable stimulus at the sensory level such as sweetness[34] or umami[35] does not simply equate to an aesthetic property of a food. Taste preferences are multifaceted, influenced by physiological, societal, cultural, and marketing factors, with aesthetic properties of foods and drinks established within communities. Further, expectations,through visual and auditory cues influence perceived food qualities,[36] with food experience beginning before ingestion, encompassing multimodal sensory information.

The time of the object (2.1) and the time of cognition (2.2) are objective, measurable, and physical temporalities. Meanwhile, the time of the phenomenon proposed in the next section is subjective time, not necessarily physical but metaphysical temporality.

3. Time of the phenomenon

The time of the phenomenon is the psychological and subjective time that accounts for the eating experience. Subjective time unfolds differently from actual (objective) time, as it can repeat, condense, pause, and so on.[37] While these temporal facets are physically hard to measure , they hold significance in characterizing aesthetic experience. Yuriko Saito emphasizes the importance of phenomenological description in order to make aesthetic experiences in everyday life the object of critical discourse and to ensure intersubjectivity. Saito claims,

A judgmental discourse, which demands a well-defined object and the potential for objectivity, falls short of encompassing the entirety of our aesthetic existence. Phenomenological description is equally indispensable to ensure that the aesthetic domain remains true to the intricate and diverse aesthetic facets inherent in our lived experiences.[38]

This section presents four temporal aspects of food appreciation. These temporal aspects may not be exhaustively listed or mutually exclusive. As detailed later, the temporality of food depends on the eater’s attitude.

3.1. Temporality 1: Non-temporal foods

The basis of temporality lies in chronological change. Food that undergoes no change in the mouth can be considered non-temporal (or atemporal) food. Food without any change in taste or flavor is not typically regarded as an object of aesthetic appreciation, at least not from the perspective of temporality. However, in principle, it is impossible for a food to remain unchanged over time. Food is affected by saliva, mastication movement, and olfactory fatigue in the oral cavity. Thus, it is more appropriate to describe the atemporality of food as a state of not paying attention to temporality rather than experiencing food without temporal properties. For example, the taste of a grain that is not one’s staple food may be perceived as atemporal. An individual whose dietary staple consists of potatoes or wheat may experience the taste of rice as atemporal, and vice versa. However, with proper attention, the differences between rice varieties, such as the texture during chewing and the sweetness of the aftertaste, can provide sufficient appreciation factors for this food.[39]

Note that a non-temporal character in food does not necessarily imply a negative quality. For instance, Japanese sake possesses an aesthetic quality known as “lightness.” This flavor quality is ideally suited to a “watery” sake with a subtle taste. Light sake is designed to complement food without overpowering its own flavor.

3.2. Temporality 2: Linear temporality

The linear perspective of time is considered as the most common image of temporality in today’s society. In linear temporality, time is perceived to flow in a singular direction, moving from the past through the present and into the future, conceptualized with metaphors of a flowing river or a flying arrow. In the concept of linear time, time is seen as irreversible, measurable, and monotonically and homogeneously increasing or changing, such as time counted in seconds. It is helpful to explore some examples appreciated within the linear temporality framework. Expressions used to describe Japanese sake, wine, and other beverages often align with linear temporality, as demonstrated in the following case from a basic sake guidebook:

Case 1: Sake comments

A mellow nose with a subtle fruity note, that’s highly distinguishable. This fragrance lingers throughout the entire sip, becoming even more pronounced just before swallowing. It is truly remarkable. The flavor is well-rounded … — Kagamiyama Ginjōshu (Saitama, Japan)[40]

Human language is well-suited to aligning with linear temporality because of its basic inherent linearity. In Case 1, time is indirectly referenced through phrases such as “nose,” “remains… into the sip,” and “just before swallowing.” Here, the “nose” signifies the top note of initial sniffing scent. The fundamental structure of an evaluative comment on sake or wine follows a sequential description of flavors, starting from the initial aroma, referred to as the “attack”), progressing to the impressions on the mid-palate, and concluding with the lingering flavors, that is, the “aftertaste” and “after-flavor”).

Case 2: The Imagination Series by Dominio IV

The Imagination Series,[41] by the Oregon’s Dominio IV winery, stands out for its label, which employs a diagrammatic representation of taste known as “shape tasting.”[42] In this series, the impression of wine taste is depicted in a two-dimensional drawing along a time axis. The shapes and colors in the drawing synaesthetically represent the taste elements. The label includes the time axis and the number of seconds, displayed at the bottom of the painting. The time is depicted from left to right, symbolically portraying the flavors as they emerge, spread, evolve, unfold, change, and linger in the mouth.

Cases 1 and 2 provide two examples of taste appreciation within the framework of linear time. In metaphysical discussions, linear temporality can manifest in various forms, such as a line segment, a half line, or an endless line, depending on the presence or absence of a distinct beginning and an end. Despite their ostensible similarity, time variations may differ entirely depending on the context of religious and cultural backgrounds.[43] However, this paper will not delve into the variations within linear temporality, as its primally focus is to contrast linear temporality with circular temporality and point temporality, as discussed further below.

3.3. Temporality 3: Circular temporality

Circular temporality regards time as cyclical, recurring, and repetitive. Examples include the endless cycle of sunset and sunrise, seasonal cycle, celestial movements, and plant growth cycles. This concept aligns with daily rhythms and is evidenced by agricultural and lunar calendars globally.

French or Italian multicourse meals have sequential, non-retrogressive, linear temporality. Conversely, in Kerala of South India meals, like Sadya (Figure 3), dishes are served on banana leaves or in bowls, without a predetermined sequence. The eater randomly consumes dishes, with some dishes repeating but in different relationships. The eater’s hand moves back and forth over the banana leaf, and side dishes are cyclically tossed into the mouth at random. Dish A may sometimes precede dish B but may also follow dish B. Dish A recurs multiple times, but it is always situated in a different relationship to the other side dishes. What previously existed appears repeatedly, and what is to come later (in the future) is what came before. The present and past are recursively repeated, passing the same point again and again. In Sadya, we see a circular temporality that cycles, repeats, and recurs.

There are countless examples of circular temporality in food. Some examples include gomokuni, Japanese curry and rice, pizza, and so on (Figure 3). Gomokuni, a Japanese dish, consists of finely chopped ingredients such as carrots, beans, kon’nyaku,kombu, burdock root, and others, simmered in soy sauce, sugar, and mirin (sweet sake). Eaten with chopsticks, it results in a random and repetitive order of ingredients. Thus, even within a single dish such as gomokuni, there is a repetitive temporality that arises when different flavors and textures appear in the mouth one after the other. Similarly, Japanese curry and rice, consumed with a spoon, offer varied textures with each scoop, creating meal rhythm. Chicago-style pizza provides a consistent taste with each bite, showing no temporal or point-time temporality. On the other hand, a Neapolitan-style margherita, for example, when eaten from the center of a piece (the apex of the triangle), offers circular temporality, with cheese, tomatoes, and basil randomly and repeatedly experienced in each bite (Figure 4). As long as servings and cutlery such as hands, spoons, and chopsticks also influence food temporality structure, as seen with gomokuni, circular temporality prevails in most dishes, while linear and point temporality are less common and are intentionally designed.

Figure 3. Circular temporality foods, from left to right: Sadya, (Japanese) curry and rice, and gomokuni. Images from Wikimedia Commons, photo-ac.com.

Figure 4. Left, Chicago style pizza; right, Neapolitan style pizza margherita;. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

3.4. Temporality 4: Point temporality

The key property of point temporality food is that all of its components unfold concurrently in the oral cavity. Thus, point temporality food often appears in bite-sized pieces,and the ingredients are wrapped or rolled. Examples in Japanese or srelated Asian food include umaki, takoyaki, gyoza (Chinese origins), and nama-harumaki (Vietnam origins). Point temporality should be viewed as condensed time, not static time. In contrast to non-temporal food (temporality 1), in which there is no sense of temporal transition, point temporality offers temporal fulfillment, whereby the entire world of the dish unfolds at once in the oral cavity.

Figure 5. Foods of point temporality,from left to right): umaki, takoyaki, gyoza (dumplings), and Vietnamese Gỏi cuốn (nama-harumaki in Japan). Umaki is a kind of egg omelet made with a center of broiled eel. Takoyaki is a ball-shaped Japanese snack, octopus-filled grilled batter balls, topped with flavorful sauces and condiments. Images from Wikimedia Commons.

Case 3: Sake Art Label Project by Obata Shuzo Brewery

In 2014, the Obata Shuzo Brewery and the Isetan Mitsukoshi Group collaborated on the Sake Art Label Project, aiming to capture sake flavors through labels (Figure 6). This project’s labels consist of five parts: a vertical sealing sticker on the cap and four sections of the main label. For Dominio IV, which follows a linear time progression from left to right, the Sake Art Label Project labels do not show a sequential or linear temporal structure. The relationship between the parts and their taste elements is not explicitly indicated, presenting a unified image across all five sections. There is no temporal precedence or subsequent order among the parts.[44]

Figure 6. Sake Art Label Project, 2014, Obata Shuzo Brewery. Artist: Takeshi Hirashima. Image provided with permission from © Takeshi Hirashima.

3.5. Short summary: the features of the temporalities in foods

In this section, I introduced four aspects of the temporality of food appreciation. Here, I summarize using sushi as an example. Sushi, comprising vinegared rice with fresh fish or seafood, includes nigiri-zushi (sushi),[45] chirashi-zushi, and maki-zushi (see Figure 7). Nigiri-zushi, the most popular style, features hand-pressed sushi rice topped with draped fish. Eaten one piece at a time and typically served side by side, it follows a linear temporality. Chirashi-zushi (literally “scattered sushi”) involves sushi rice topped with assorted ingredients, offering a non-linear experience with no predetermined consumption order, resulting in circular temporality like that of a Neapolitan margherita pizza. Maki-zushi (rolled sushi), presents rice wrapped in nori seaweed, making a point-time food experience, similar to dumplings.

Figure 7. The variations of sushi offer good examples of food temporality. From left to right: nigiri-zushi (linear temporality), chirashi-zushi (circular temporality), and maki-zushi (point temporality). Images from free-materials.com.

3.5.1. The temporality of food depends on the eater’s attitude

These four temporalities aren’t mutually exclusive; one food can offer multiple temporal aspects. Food’s temporality is not predetermined before consumption. Every food can be experienced in linear temporality or appreciated by focusing on circular temporality. No single temporality is superior to another. For example, with gomokuni, carrots and other ingredients are finely chopped. Eating with chopsticks, only one or two pieces can be picked up at a time. Microscopically, ingredient experiences occur linearly, but at the dish level, circular temporality arises with repetitive ingredient textures. Consuming gomokuni with a dinner spoon can produce a point-time experience.

Temporal aspects vary with the eater’s awareness, attention, and attitude. In sadness, everything tastes bland, as if time is absent. Yet, even in foods with point temporality, in-mouth events can be linearly or cyclically described, with deep reflective attention. Thus, food’s temporality depends on the eater’s attention and attitude.

3.5.2. Constraints lead to temporality

Time, or temporality, does not independently exist outside of human cognition. It gains meaning through memory and oral capacity constraints. Natural intelligence cannot equally reproduce past stimuli because of memory limitations (short-term, long-term, and sensory memory). Memory fades, undergoes editing, and significant memories are emphasized. On the other hand, the machine’s memory can reproduce the same input stimuli of ten years ago; it can taste the present coffee and ten years ago coffee “at the same time.” For the machine, time does not intervene in the comparison of input values. This means that the machine’s time is essentially point time.

Physical constraints like oral cavity volume affect temporality. The division of food results in units of temporality such as sequence and repetition. Ten pieces of nigiri-zushi have a linear structure because only one piece can be placed in the mouth at a time. If a machine has a large “mouth,” the ten pieces can be viewed simultaneously as a point temporality.

Temporality enables taste appreciation through cognitive and physical constraints. It is perceived diversely based on the eater’s attention and attitude. Each food does not have inherent temporality; some appreciate pizza margherita in circular time, others in linear time, depending on their focus and attitude.

4. Discussion

4.1. Different temporality, different thoughts

Barbara Tversky critiques the linear bias, the sole reliance on linear temporality. Her studies on gestures and thoughts argues that “the change of perspective, from linear to circular, enables new discovery.”[46] Tversky’s case study shows how changing one’s time perspective impacts thought processes. Her experiment parallels this study, demonstrating how thinking varies based on time perspective.

Examining wine appreciation through only linear temporality is a narrow perspective. Like considering the ninth baseball batter as “before the first” rather than “the last,” we should not overlook that the “after-flavor” precedes the “top note” of the next glass. Describing flavor only in the moments between wine entering the mouth and being swallowed oversimplifies the experience. A list of wine flavors doesn’t capture its aesthetic appreciation. A formulaic, linear description obscures the joy of repeated sips. Japanese fixed phrases such as “sakazuki wo kasaneru” (“to drink more cups”) and “nomi susumeru” (“to drink more”) emphasize that the essence of sake or tea appreciation lies in repetition. The Lu tong’s (盧仝, A.D. 790-835, Tang Dynasty in China) “Seven Bowl Tea Poem” depicts this repetitive appreciation:

一碗喉吻潤 [The first bowl moistens my lips and throat]

二碗破孤悶 [The second bowl breaks my loneliness]

三碗搜枯腸 [The third bowl searches my barren entrails but to find]

惟有文字五千卷 [Therein some five thousand scrolls]

四碗發輕汗 [The fourth bowl raises a slight perspiration]

平生不平事盡向毛孔散 [And all life’s inequities pass out through my pores]

五碗肌骨清 [The fifth bowl purifies my flesh and bones]

六碗通仙靈 [The sixth bowl calls me to the immortals]

七碗吃不得也 [The seventh bowl could not be drunk]

唯覺兩腋習習清風生。 [Only the breath of the cool wind raises in my sleeves]

蓬萊山、在何處、玉川子乘此清風欲歸去。

[Where is Penglai Island? Yuchuanzi wishes to ride on this sweet breeze and go back]

(Translation by Steven R. Jones, 2008; edited by the author)[47]

The poem depicts the mind’s journey through seven bowls, emphasizing cyclical rather than linear time. Japanese philosopher Shuzo Kuki (1888-1941) argues that the rhyming can represent circular time.[48] Kuki proposes that transmigration, an endless cycle or reincarnation, is a significant aspect of East Asian temporality, and the circular temporality is expressed through rhyming in Japanese short verse forms like tanka and haiku. The concept applies to Lu Tong’s poetry: 潤rùn 悶mèn/mēn 腸cháng 卷juǎn/juàn 汗hàn 散sǎn/sàn 清qīng 靈ling 生shēng. The rhyme repeats from the first to the eighth line, interrupted by another sound in the ninth line (也yě), but resumes in the next line (生shēng), implying an infinite cycle.

As Tversky highlights, different temporalities lead to different thoughts. Considering food solely in linear time overlooks its complexity, and introducing circular temporality opens up new possibilities for food appreciation, as demonstrated in Lu Tong’s poetry. This circularity extends beyond the physical. We will explore the metaphysical implications in the next part.

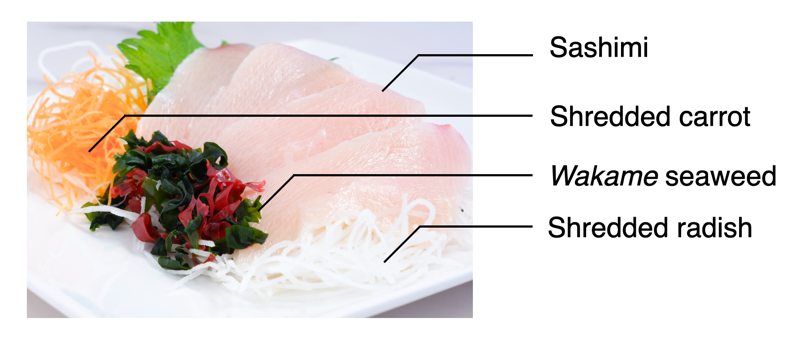

4.2. Our eating experience is embedded in the multilayered cyclical temporality

Food appreciation hinges on a multilayered cyclical temporality. Layers of cyclical rhythms further enrich the experience: appetite cycle, breathing cycle for olthonasal/retronasal flavor, and mastication and tongue rhythm for revealing texture. Food preference learning encourages this repetition, while aversion learning disrupts this cycle serving a survival purpose. Culinary art strives for harmony within this intricate cyclical structure. Texture plays a pivotal role in Japanese cuisine, where chefs meticulously combine ingredients to create a symphony of sensations during mastication. Renowned Japanese chef Kaichi Tsuji emphasizes the importance of shredded daikon radish, often seen as garnish for sashimi. According to Tsuji, the soft texture of the sashimi is accentuated by the radish, but it is important to find a balance where the radish is not too prominent. He also notes that garnishes with different textures such as crisp bamboo shoots, udo, and soft wakame seaweed can be added to provide a stimulating experience of eating.[49]

Figure 8. Sashimi and garnishes. Image from photo-ac.com.

4.3. From the focal point, time extends into the past and the future

Tsuji suggests that gastronomy’s core lies in creating varied textures within a dish, forming a rhythm during chewing. This rhythm is within multilayered, cyclical temporality, where beginnings and endings hold less significance, akin to the continuous orbit of the sun and moon. Viewing time cyclically means perceiving it as a circle without a distinct start, middle, or end, as Tversky and Kessell explain.[50] However, just as there exists sunrises and sunsets, or summer and winter, cyclical time has a focal point from which the progression of time is realized.

In discussing cognitive theory ,this focal point, or the “origin of the cognition,” is addressed using various terms such as ‘figure’ in figure and ground[51] ‘trajector and landmark,’[52] ‘cognitive salience,’ and ‘prerogative moment.’ In cognitive linguistics, the trajector and landmark constitute the referential point structure, forming the basis for constructing linguistic representations of situations and events. Like vision, in taste a figural subject or structural center emerges within cyclical time, providing a framework for tasting experiences.

No temporality can arise without change or movement. In cyclical time, change generates the past and future from the origin of cognition onward. Souriau terms this focal point the ‘prerogative moment’ and argues that:

As for this intrinsic time of the plastic work, one can say that its organization, in general, is stellar and diffluent. The time of the work radiates, so to speak, around the prerogative moment represented. The latter makes a structural center from which the mind moves backward to the past and forward to the future in a more vague fashion until the image fades gradually into space.[53]

In culinary temporality, a dish comprised solely of “ground” elements would lack temporal dynamics. Even well-seasoned food can succumb to olfactory adaptation or fatigue. The principle of introducing a change point (prerogative moment) for overall harmony likely extends across various art forms including music and visual arts. Achieving this moment with food entails using wasabi and soy sauce judiciously with sushi or sparingly adding mustard to roast beef rather than smothering it.

In addition to textural variations, prerogative moment lies in the drinking experience. From the tongue’s perspective, wine is not a homogeneous pool but a dynamic environment with currents and stagnation, similar to a river. Wine undergoes interactions in the mouth including retention, agitation, and reaction to salivation. In this context, the image of wine is perceived through gradations of information (texture gradients by J.J. Gibson[54]). Wine exhibits gradients, shades, and focal points of information through our interaction with a texture-saturated environment, constituting an interplay of figure and ground, namely the prerogative moment and fundamental flow.

To create textural variation or the prerogative moment during chewing, a basic cognitive flow serves as the ground. For example, fukujinzuke (a red, crispy pickle condiment) in Japanese curry and rice dish provides the prerogative moment. Compared to spicy Indian curries, Japanese curry and rice tends to have a monotonous taste (see Figure 3). The combination of thick, mushy curry roux, soft rice, and tender vegetables is the main ground stream, but does not encompass Souriau’s prerogative moment. Here, the crunchy texture and fresh flavor of fukujinzuke are nothing short of a privileged moment that elevates a curry to a work of art. All the temporality of roux, rice, and potatoes is only realized retroactively into the past and diffusely into the future by this prerogative, focal moment of the structure.

5. Summary

Some pizzerias strategically place fewer ingredients in the center of pizza margherita to prevent spillage and intensify taste when eating from the tip of a slice. Linear temporality is designed within a single piece and maintained in V-fold style, but altered in turnover style, shifting to point temporality. Thus, food can have multiple temporalities; pizza margherita can represent gradations of taste or cyclical temporality with the prerogative moment by including basil amidst repeating ingredients. When eaten turnover style, gradation and repetition converge into point temporality. Italians would regard it as different cuisine, giving the turnover-wrapped style another name: calzone.

This study categorized taste appreciation into three temporalities: the time of the object, the time of cognition, and the time of the phenomenon. Further, some culinary examples illustrated four temporal aspects of the time of the phenomenon: non-temporality, linear, circular, and point temporality. These aspects are influenced by our cognitive and physical constraints, eater awareness, attention, and attitude.

Spatial nature of food is a future research topic. Exploring mental spatiality expansion, not physically measurable, poses a challenge. Though oral and nasal cavities have physical space, aromatic wine or whiskey image spreads over a larger space than the physical nose. The temporality theory provides a convincing basis for aesthetic appreciation of taste and smell when discussed in relation to mental and metaphysical spatiality.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 20K20127. I would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments refined my content, enabling a focused discussion on Japanese and Asian cuisine.

Hiroki Fxyma

h.fxyma@gmail.com

Hiroki Fxyma is an assistant professor at Kobe University in Japan. His research interest focuses on the aesthetic experience and appreciation of the taste and flavor. He is a member of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence and is working on archiving food experiences.

Published on September 10, 2024.

Cite this article” Hiroki Fxyma, “The Temporality of the Aesthetic Appreciation of Food and Beverages,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Volume 22 (2024), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] V-fold style: Fold the pizza crust in half into a v-shape. Turnover style: Fold the top of the pizza triangle toward the crust.

[2] The background to the philosophical neglect of taste and flavor is discussed in detail in recent Barwich’s work: A. S. Barwich, Smellosophy: What the Nose Tells the Mind (Harvard University Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674245426.

[3] Frank Sibley, “Tastes, Smells, and Aesthetics,” in Approach to Aesthetics: Collected Papers on Philosophical Aesthetics, ed. Frank Sibley et al. (Oxford University Press, 2001), 0, https://doi.org/10.1093/0198238991.003.0015.

[4] Tiziana Andina and Carola Barbero, “Can Food Be Art?,” The Monist 101, no. 3 (2018): 353-61.

[5] Larry Shiner, “Art Scents: Perfume, Design and Olfactory Art,” The British Journal of Aesthetics, October 7, 2015, ayv017, https://doi.org/10.1093/aesthj/ayv017, 379.

[6] Douglas Burnham and Ole Martin Skilleås, The Aesthetics of Wine, 1st ed. (Wiley, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118323878.

[7] M. W. Rowe, “The Objectivity of Aesthetic Judgements,” British Journal of Aesthetics 39, no. 1 (1999): 40-52.

[8] Masaki Suwa, “Methodological and Philosophical Issues in Studies on Embodied Knowledge,” New Generation Computing 37, no. 2 (April 1, 2019): 167-84, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00354-019-00055-1; Otsuka Hiroko, Suwa Masaki, and Yamaguchi Kengo, “Studies of Expressions to Taste Japanese Sake by Creating Onomatopoeia” (Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, 2015), https://doi.org/10.11517/pjsai.JSAI2015.0_2N5OS16b5.

[9] Emily Brady, “Smells, Tastes, and Everyday Aesthetics,” in The Philosophy of Food, ed. David M. Kaplan (University of California Press, 2019), 69-86, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520951976-005.

[10] Mădălina Diaconu, “Reflections on an Aesthetics of Touch, Smell and Taste,” Contemporary Aesthetics 4, no. 8 (2006).

[11] Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste: Or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy; Introduction by Bill Buford (New York: Everyman’s Library, 2009), 59.

[12] “Sui Yuan Shi Dan ; 隨園食單,” Chinese Rare Books – CURIOSity Digital Collections, accessed May 1, 2024, https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/chinese-rare-books/catalog/49-990080539850203941.

[13] Larry Shiner and Yulia Kriskovets, “The Aesthetics of Smelly Art,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 65, no. 3 (2007): 273-86.

[14]café-sweets, “cafe-sweets vol. 212 -Assiette dessert and Parfait [Saramori deza-to to pafe],” Shibata Shoten, 2022.

[15] Café-sweets.

[16] “Dominique Bouchet Kyoto 「Le RESTAURANT」,” Dominique Bouchet Kyoto 「Le RESTAURANT」, accessed May 1, 2024, https://www.miyakohotels.ne.jp/westinkyoto/restaurant/dbr/.

[17] Etienne Souriau, La Correspondance Des Arts, Éléments d’esthétique Comparée (Paris: Flammarion, 1969). Souriau criticized all dichotomous classifications, including those of temporal and spatial art. He analyzed arts in parallel according to their correspondences, that is, their underlying common structure. In Time in the Plastic Arts, Souriau argues that temporality is as essential to the appreciation of paintings and sculptures as it is to that of music or literature.

[18] John Dewey, Art as Experience. (New York: Berkeley Publ. Group, 2005), 228. Dewey considers both spatiality and temporality are fundamental components of the five major arts (architecture, sculpture, painting, music, and literature) and claims, “even a small hut cannot be the matter of esthetic perception save as temporal qualities enter in.”

[19] Cain Samuel Todd, The Philosophy of Wine: A Case of Truth, Beauty, and Intoxication (Montréal [Québec] ; Ithaca [N.Y.]: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010), 40.

[20] Charles Spence, “Oral Referral: On the Mislocalization of Odours to the Mouth,” Food Quality and Preference 50 (June 2016): 117–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.02.006.

[21] Keith A. Wilson, “The Temporal Structure of Olfactory Experience,” In Benjamin D. Young & Andreas Keller (eds.), Theoretical Perspectives on Smell. Routledge. pp. 111-130.

[22] Diaconu, “Reflections on an Aesthetics of Touch, Smell and Taste.”

[23] Barbara Gans Tversky, Mind in Motion: How Action Shapes Thought (New York: Basic Books, 2019).

[24] National Research Institute of Brewing, “List of Standard English Expressions for Sake Terminology (Sake Terms),” 2021, https://www.nrib.go.jp/sake/st_info.html.

[25] Yoichiro Kanno et al., “Visualization of Flavor of Sake Using Taste Sensor and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry,” IEEJ Transactions on Sensors and Micromachines 140, no. 11 (November 1, 2020): 294–304, https://doi.org/10.1541/ieejsmas.140.294.

[26] Kent Bach, “Knowledge, Wine, and Taste: What Good Is Knowledge (in Enjoying Wine),” in Questions of Taste: The Philosophy of Wine, ed. Barry C. Smith (Oxford University Press, 2007), 21-40.

[27] Todd, The Philosophy of Wine, 40.

[28] Julien Delarue and Eléonore Loescher, “Dynamics of Food Preferences: A Case Study with Chewing Gums,” Fifth Rose Marie Pangborn Sensory Science Symposium 15, no. 7 (October 1, 2004): 771-79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2003.11.005.

[29] The “time of the object” in the previous section is a temporality that is independent of the eater, but eating is the process by which an external object becomes eater-self, thus the boundary between these two times would not have to be so clear-cut.

[30] James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition, 1st ed. (Psychology Press, 2014), 138-139; italics mine. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740218.

[31] Gordon Shepherd, Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why It Matters (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013).

[32] “The technique is to roll the whiskey (particularly Bourbon) around in the mouth and “chew” on it, which allows the spirit to reach all the surfaces of the mouth, which pick up different flavors.” Kara Newman, “How to Taste Whiskey,” Wine Enthusiast, 2017, https://www.winemag.com/2017/05/18/how-to-taste-whiskey/.

[33] I.L. Bernstein, “4.23 – Flavor Aversion Learning,” in The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference, ed. Richard H. Masland et al. (New York: Academic Press, 2008), 429-35, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012370880-9.00097-9.

[34] Danielle R. Reed, Toshiko Tanaka, and Amanda H. McDaniel, “Diverse Tastes: Genetics of Sweet and Bitter Perception,” Physiology & Behavior 88, no. 3 (June 2006): 215-26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.033.

[35] B. J. Cowart, “Taste, Our Body’s Gustatory Gatekeeper,” Cerebrum 7, no. 2 (2005): 7-22.

[36] D. Labbe, N. Pineau, and N. Martin, “Food Expected Naturalness: Impact of Visual, Tactile and Auditory Packaging Material Properties and Role of Perceptual Interactions,” Food Quality and Preference 27, no. 2 (March 2013): 170-78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.06.009.; Olga Ampuero and Natalia Vila, “Consumer Perceptions of Product Packaging,” Journal of Consumer Marketing 23, no. 2 (February 2006): 100–112, https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760610655032.

[37] Although the definition of psychological time is not uniform among the authors, it is basically discussed in contrast to measurable physical time. For example, Alexis Carrel, in a 1931 paper, classifies the time experienced by living organisms into two classes: rhythmical and reversible, or progressive and irreversible. Yamada and Kato propose the temporality of circular time and spiral repetition as The Generative Life Cycle Model. Alexis Carrel, “Physiological Time,” Science 74, no. 1929 (1931): 618-21; Yoko Yamada and Yoshinobu Kato, “Images of Circular Time and Spiral Repetition: The Generative Life Cycle Model,” Culture & Psychology 12, no. 2 (June 2006): 143-60, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X06064575.

[38] Yuriko Saito, “Aesthetic Values in Everyday Life: Collaborating with the World through Action,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 81, no. 1 (May 18, 2023): 96-97, https://doi.org/10.1093/jaac/kpac068.

[39] Japan Grain Inspection Association, “Rice Taste Test,” accessed May 1, 2024, https://www.kokken.or.jp/test.html.

[40] D. Labbe, N. Pineau, and N. Martin, “Food Expected Naturalness: Impact of Visual, Tactile and Auditory Packaging Material Properties and Role of Perceptual Interactions,” Food Quality and Preference 27, no. 2 (March 2013): 170-78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.06.009.

[41] For the image of the Imagination Series labels, see also following article; “You Don’t Need to Speak Wine to Read These Labels” https://www.vice.com/en/article/wnbdjq/you-dont-need-to-speak-wine-to-read-these-labels.

[42] “The Shape of Wine,” Oregon Wine Press, accessed May 1, 2024, http://www.oregonwinepress.com/the-shape-of-wine.

[43] The time variations among regions and religions are discussed in detail in Shuichi Kato’s Time and Space in Japanese Culture. Kato classifies temporality according to whether it has a beginning (creation of the world) or an end (eschatology): segmental time (Judeo-Christian), semi-linear time (ancient Greek), no beginning and no end (early Japanese Kojiki), cyclical time (Buddhism), and further subdivisions. Shuichi Kato, Time and Space in Japanese Culture [Nihon Bunka Ni Okeru Jikan to Kūkan] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2007).

[44] In this point, the circular temporality and the point temporality are analogous (the circle becomes a point when it is reduced or overviewed), but this label is intended to be an unordered, simultaneous unfolding of all elements (point time) rather than a repetition (circular time).

[45] In Japanese, when the word ’sushi’ is combined with other words, it often changes to ’zushi.”’For example, nigiri + sushi becomes ’nigiri-zushi.’

[46] Barbara Gans Tversky, Mind in Motion: How Action Shapes Thought (New York: Basic Books, 2019).

[47] Japan Grain Inspection Association, “Rice Taste Test,” accessed May 1, 2024, https://www.kokken.or.jp/test.html.

[48] Shuzo Kuki, Jikanron [The Theory of Temporality], ed. Yoshinobu Obama (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2016).

[49] Kaichi Tsuji, Mikaku zanmai [Nothing but Taste], (Tokyo: Chuokoronshinsha, 2002).

[50] Barbara Tversky and Angela Kessell, “Thinking in Action,” Pragmatics & Cognition 22, no. 2 (December 31, 2014): 206-23, https://doi.org/10.1075/pc.22.2.03tve.

[51] Leonard Talmy, “Figure and Ground in Complex Sentences,” in Universal of Human Language, ed. J.H. Greenberg, vol. 4 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1978), 625-49: 627.

[52] Ronald W. Langacker, Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. 2: Descriptive Application, (California: Stanford University Press, 2006).

[53] Souriau, “Time in the Plastic Arts,” 301 [emphasis added].

[54] James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition, 1st ed. (New York: Psychology Press, 2014), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740218.