The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

Vitality Semiotics: The Ever Beautiful and Its Potential for an Intercultural Approach

Martina Sauer

Abstract

Two landscapes from different cultures, Europe and China, that are both considered masterpieces are the focus of this study. To what extent are they each perceived as beautiful? Can the differences in aesthetic understanding tell us something about the respective cultures? Do the results have the potential to contribute to intercultural rapprochement between Europe and China? The possibility that these ideas can be fruitful for intercultural connections and understanding, and for a reevaluation of the interaction between humans and nature, will be considered and analyzed using the tools and theory of vitality semiotics (VS). To this end, its premises in philosophy and image science, art history, infant research, and neuroscience are first introduced before the two examples are analyzed. The latter is done with the methodological tools of formal aesthetics that was developed in German-speaking countries. It builds in relation to the initial questions based on the analysis of aesthetically and culturally relevant abstract forms. This approach is extended by affective, semiotically relevant aspects of VS that bring the question of an intercultural approach into focus.

Key Words

vitality semiotics (VS); formal aesthetics; vitality affects and forms; the ever beautiful; intercultural rapprochement

1. Introduction

Aesthetic experiences develop in socio-evolutionary processes, said the German philosopher Sabine A. Döring (2010).[1] According to her, what is perceived as beautiful depends on the cultural development of societies. It is reflected through specific family resemblance. Against this backdrop, it is the respective cultural atmospheres that are expressed in the specific aesthetic realities. Understanding and evaluating and rejecting and accepting another culture therefore depends on distinguishing and evaluating that culture from one´s own.[2] The prerequisites for recognizing the differences of aesthetic realities can be explained by an approach based on comparative analyses of different art epochs in Europe. It was introduced at the beginning of the twentieth century by the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin, in 1915,[3] and is based on the assumption that there is an analogy between the ways of designing or composing design elements and the ways of worldview and thus the different cultural atmospheres.[4]

Developmental psychological studies on infants conducted by Daniel N. Stern in 1985 support this approach. They put forward the idea that not only are the perception of the world and social interaction based on the same premises but also the perception of art, as Stern suggested citing the philosopher Susanne K. Langer.[5] His conclusions are derived from findings about human perception that are based on nondiscursive forms. In this context, it is essential to realize that we interpret them as living forms or so-called vitality forms.[6] This led to the approach of vitality semiotics (VS) that I advocate. It is based on the assumption that the perceived vitality forms in art not only convey a representational content characterized by moods, as Stern and Langer still assumed, but, in addition, can be considered as a means of communication between people.[7] I have been pursuing this concept since 1998 with a discussion of why abstract forms become important in art, incorporating semiotic, culturally relevant meanings from the outset.[8] However, I only recently summarized this approach under the heading VS.[9] Building on this concept, it becomes clear that artistic realities also can contribute to an intercultural harmonization or a transcultural approach to the respective atmospheres of cultures. In this case, it is less the sociopolitical questions that I raised in 2012 in Fascination – Horror: On the Relevance of Aesthetic Experience for Action on the Basis of Anselm Kiefer’s Pictures of Germany,[10] than the respective sense for the beauty as expressed in the aesthetic realities of cultures and the corresponding aesthetic experiences of a person touched by them, that enables a harmonization of different atmospheres and thus of cultures.

Against the background of the VS concept and in order to show the basis for a possible rapprochement between different cultures with regard to what they each perceive as beautiful, the article is divided into three sections. In a first step, the already outlined prerequisites for solving the task in the VS concept are presented in more detail. These prerequisites lie in philosophy and image science, art history, infant research, and neuroscience. In a second step, a comparative analysis of the design of atmospheres in two representative examples from two cultures follows — Europe and China. Finally, in a third step, the potential of a cross-cultural approach to the question of what each culture perceives as beautiful is demonstrated.

2. Premises of vitality semiotics

Seeing in VS’s concept the potential to present an intercultural approach to the encounter of different cultures, using its respective understanding of beauty as a starting point is promising. This is because VS deals with the fundamentals of what constitutes experience and knowledge and the sharing of them with others. It focuses on abstract, affective, semiotically relevant forms that constitute the world, social interaction, and the fundamentals of the universal formation of culture(s). Remarkably, it seems to be the conscious experience of the formative means in art that can open up the eyes not only to differentiation of cultures but also to their connection (cf. Fig. 1). This path is intended to contribute to the intercultural rapprochement between Europe and China.

|

Definition and objective of VS in terms of what constitutes experience, knowledge, and their sharing with others:

Grounded in abstract, affective, and semiotically relevant forms.

Has relevance to the constitution of world, social interaction, and culture(s).

Has the potential to recognize the differences in the cultures as well as to bring them together.

|

Fig. 1. Definition and objective of VS by Martina Sauer.

2.1 Premises from philosophy of emotion: Sabine A. Döring

As pointed out in the introduction, in aesthetic theory it is the German philosopher Sabine A. Döring who in 2010 emphasized that emotional responses to art do not depend on anything outside of us, but are based on interaction with the world and others. The emotional evaluations in art by the viewer such as beautiful, sublime, admirable, somber, cool, frightening, and so on are acquired in social-evolutionary processes and are fundamentally non-functional.[11] In this case, research speaks of discursive emotions. Thus, it can be confirmed that the “ever beautiful” is different in Western and Eastern cultures. It is evaluated according to family resemblance. Aesthetic reality is thus a cultural atmosphere. Its acceptance or rejection depends on the distinction from one´s own culture.

However, this result contrasts with a second finding in 2002 pointed out by the same researcher, together with her colleague, Christopher Peacocke, from the USA. There, they stated that our emotions, when they are specifically directed at something outside of us, can be understood not only as intentional but also as representational. They correspond to emotions that are directly related to what triggers the emotion. Basically, they are functional. In this way, according to the two researchers, emotions “represent an irreducible category in explaining and rationalizing actions. (…) Emotions are therefore necessarily evaluations.”[12] (See Fig. 2 for comparison and consequences for VS.)

|

2002 Triggered by something outside = functional.

Emotions can therefore be understood as intentional and representational.

Through them an evaluation of possible actions is made. |

2010 Basis is interaction with the world and others = non-functional.

Aesthetic experiences develop in socio-evolutionary processes.

Consequences concerning VS

The ever beautiful is different in Western and Eastern cultures.

It is valued by family resemblance.

Aesthetic reality is a cultural atmosphere.

Acceptance or rejection depends on distinction from one´s own culture.

|

Fig. 2. Theories of emotions in everyday life (Döring and Peacocke 2002) and art (Döring 2010) and consequences for VS by Martina Sauer

Both irreconcilably contradicting findings are important for VS. I argue that not only emotions that develop in socio-evolutionary processes and are conveyed by the art of a culture but also the emotions that are triggered by the artifacts themselves can be seen as fundamental to a person´s value judgment. In this respect, the encounter with art is not only important for confirming one´s own cultural preferences, but also for action and thus for processes of cultural value formation. As such, it opens up the possibility of stimulating not only differentiation and comparison but also approaches to other cultures. In this case, it is less the content-related information than the aesthetically relevant aspects and their recognizable inherent values that may open up ways for comparison and thus for rapprochements.

2.2 Premises from art history: Heinrich Wölfflin

In art history, it is the analysts of formal aesthetics from the German-speaking world who have analyzed the differences in the aesthetic perception of cultures between European epochs since the nineteenth century, from the late Roman period through the Middle Ages and Humanism to Modernism. For them, the perceptual characteristics of the artifacts are the basis for their differences and not possible philosophical theories or aspects of content. These researchers advocate an approach as presented by Heinrich Wölfflin in 1915, in which the how (the form) is seen as essential for the what (the cultural preferences).[13]

Against this backdrop, the formal choices of artists and their aesthetically relevant effects on the viewer are essential for identifying the respective cultural preferences, in this case of European epochs. Wölfflin comes to the conclusion that “one could envisage a history of the development of occidental seeing.”[14] Thus, cultural differences depend on which forms one chooses (for example, linear or painterly), whether and which colors one chooses, what tools, materials, and carriers one chooses, and how one uses them. It is the trace of a line (impasto, transparent, or flat, for example), the effect of colors or non-colors (for example, intensity, brightness, and contrast) that is considered essential to the evaluation of cultural preferences. It is assumed that the aesthetics that each culture perceives as beautiful is determined by how it relates forms and colors to materials and carriers and also to content or function.[15]

Essentially, according to VS, these differences provide information about different ways of seeing the world (in German, Anschauungsweisen)[16] not only in relation to sociopolitical issues[17] but also about different cultural moods or atmospheres.[18] The latter is the subject of this essay with regard to a possible rapprochement of cultures. At the center of this is the idea that there are analogies between world views and aesthetic feelings of the respective culture and the means of design used. This assumption is indirectly confirmed by recent research from developmental psychology, infant research, and the neurosciences that will now be presented in more detail.

2.3 Premises from infant research: Daniel N. Stern

The central finding in 1985 by the American developmental psychologist and infant researcher Daniel N. Stern is that human perception is based on nondiscursive forms and their vivid processing on so-called vitality affects,[19] or vitality forms.[20] More precisely, as numerous experiments have shown, everyday perception is oriented towards “shapes, intensities, and temporal patterns.”[21] It is only through their vivid processing that the interpretation of what is perceived takes place. Stern sees this a direct link to art. After all, art is also based on the processing of abstract elements. In his later study on them (2010), he limits himself to the performative arts.[22] However, instead of ensuring social interaction, as Stern assumes with regard to direct communication, art primarily appeals to the mood of the viewer.[23] Extending Stern´s original approach, the concept of VS leads to the thesis that not only perception in general, as Stern puts it,[24] but also the perception of art ensures social interaction. Furthermore, the concept follows the idea that perception not only serves direct communication between people but also between groups or cultures via media (cf. Fig 3).[25]

|

VS premises about art perception are based on everyday perception

As in everyday perception, the perception of art is based on nondiscursive forms, ´vitality forms´ and their lively processing as ´vitality affects´: shapes, intensities, and temporal patterns.

As in everyday life, so in art perception serves to ensure social interaction between groups or cultures.

VS is a concept of analogy between formative means of art and modes of perception.

|

Fig. 3. Art perception is based on everyday perception by Martina Sauer.

2.4 Premises on art perception from neuroscience: research group around Giacomo Rizzolatti

Stern´s concept coincided with the research questions of a group of Italian neuroscientists led by Giacomo Rizzolatti, who in 1996 linked their discovery of so-called mirror neurons to the human capacity for empathy.[26] In a joint research group with Stern, they deepened their research and published their findings in 2013.[27] More recent research also suggests that not only human behavior and language[28] but also the art itself evokes vital sensations through forms that are perceived as vitality forms.[29] The focus is no longer only on the performative arts, as with Stern, but also on the material arts. Through them, the artists also convey their moods.[30] These moods, it should be added with regard to my approach here, are closely linked to the creator´s own culture. And the respective viewer compares them with his or her own mood or cultural atmosphere. This expanded thesis will be demonstrated in a comparative study in the following second chapter (cf. Fig. 4).

|

Extended thesis of VS concerning intercultural rapprochements via art

Perception is based on ´vitality affects´ or ´vitality forms´ in art.

It communicates artist´s mood or his or her cultural atmosphere.

It serves coordination processes with the viewer´s mood or cultural atmosphere.

|

Fig. 4 Intercultural rapprochements via art by Martina Sauer.

3. Application: aesthetics of atmospheres in two cultures: Europe – China

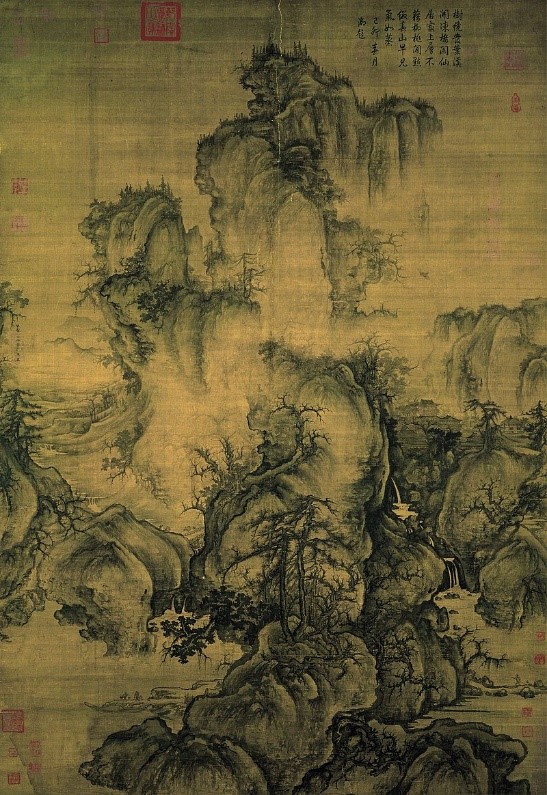

As examples of the approach pursued here, two paintings that are valued and recognized as significant in Europe and in China are analyzed in terms of their aesthetics or the moods they embody. One is a landscape painting by the French Impressionist Paul Cézanne, from the beginning of the twentieth century in Europe (Fig. 5), and the other is the monochrome Chinese landscape by Guo Xi, from the eleventh century (Fig. 6). Both are recognized as masterpieces. But what distinguishes them? What makes each be recognized as beautiful? Can they tell us anything about the culture in question and its understanding of beauty? Do the results have the potential to appeal to an intercultural rapprochement between Europe and China?

The painting by Paul Cézanne, Sous-Bois (Underwood, my translation from French), dates from 1900-1902. Cézanne reduced his formative means to so-called ´taches´ (blots, my translation from French). These are more or less square blots of brushstrokes in different colors. It is precisely these small blots that make up the composition. But what can we recognize in it? What about the shapes or forms? That is interesting, because we are almost lost in this question. We recognize steps that lead upwards or downwards. We also interpret the blue, green, and brown blots on the left and right and above as leaves from trees and bushes, without being able to clearly recognize them. The white marks are not painted blots, but gaps and therefore empty spaces on the canvas. What we see are therefore only colored blots and a few lines that give the impression of a small section of a landscape. In contrast, and that is disturbing, we realize the bodily appearance of recognizable motifs. And this is despite the fact that we, as viewers, cannot fix the colored blots for a correct motif in a well-ordered space. On the contrary, they can only be interpreted in front or behind, above or below, almost anywhere. In the end, all these colored blots do not form a spatial order, but convey an almost physical or bodily impression of several natural elements mixed together in space. Once caught by this impression, a landscape full of colors, light, movements of rustling leaves, branches, and a staircase, under a bright blue sky, presents itself. Ultimately, only the steps give us orientation and thus a foothold. These impressions convey an instantaneous and therefore brief moment of feeling at one with nature. In this moment, the impression of feeling connected to a landscape is more real than ever before, even or precisely because we cannot clearly recognize it. We are the ones who experience or bodily feel it. The landscape becomes a form and loses it: natura naturans and natura naturata.[31]

A similar sense of becoming and passing away characterizes the drawing on silk by the Chinese artist Guo Xi, Early Spring, from the beginning of the eleventh century. Instead of blots of colors, his composition is dominated by lines. They are in a certain tension with the delicate lines of the silk fabric itself, which characterize the ground and give way to an open, indifferent space. In it or on it, independent lines develop from bottom to top, passing from darker, more earth-heavy lines to lighter, brighter, and more ephemeral lines. They behave freely, like an autonomous force, forming mountains and trees that rhythmically grow upwards. In this way, the lines lose their dependence on the empty space formed by the silken ground, on the one hand, and on the other, they are connected to it by the negative cloudy forms they form. Finally, Chinese characters in black and red at the top and bottom left and right complete the composition and connect it to people. Zhuofei Wang summarizes her interpretation, which I agree with, as follows:

Through the interrupting function of the clouds in the painting, the mountain landscape appears as both emerging and submerging, and thus exudes an atmosphere that is fascinating, inexhaustible, and seemingly endless. Ultimately, life and movement are brought to the forefront of the aesthetic experience.[32]

In summary, it can be said there is a strong contrast that characterizes the two landscapes. They are instantaneity and infinity, and thus two different moods of the viewer and at the same time atmospheres of nature, which meet here in the description of the two landscapes of significance in Europe and China. Ultimately, it is astonishing, because both mark the now and the eternal. In Cézanne´s painting, the moment remains forever anchored in the viewer´s feeling; in Guo Xi´s drawing, infinity remains forever entangled in the viewer´s feeling. It is the connection with nature, its colorful, vivid beauty and richness on the one hand, and its obscure immensity on the other, whose atmospheres one senses. It is therefore the bodily momentary and the eternal spatial feeling of the unity of nature and man that arises from the unity of atmosphere and mood (cf. Fig. 7).

|

Landscape of Cézanne

Impression of nature

This impression is based on material-bound formative means reduced to blots, which are more or less square blots of brushstrokes in different colors.

Triggered by them, the “full” space can be experienced as a ´body´ of nature and human.

Triggered by them, a mood of feeling in unity with nature is conveyed. It is marked by instantaneity. The moment keeps forever in the viewer´s feeling.

The painting conveys an atmosphere of momentary impression, in which nature becomes form (a body) and then loses this form or bodily impression by blurring it in individual brushstrokes.

|

Landscape of Guo Xi

Eternal nature

This impression is based on material-bound formative means reduced to lines, which develop from bottom to top, passing from darker, more earth-heavy lines to lighter, brighter and more ephemeral lines.

Triggered by them, the empty space can be experienced as unity of nature and human.

Triggered by them, a mood of feeling in unity with nature is conveyed. It is marked by infinity. It keeps forever in the viewer´s feeling.

The drawing conveys an atmosphere of an eternal nature, in which nature emerges and submerges.

|

Fig. 7 Comparison between two landscapes as examples: aesthetics of atmospheres in Europe and China by Martina Sauer.

4. Conclusions: The ever beautiful and its potential for an intercultural approach

Finally, a few words to summarize: the unity of nature and humans—in the moment and in eternity, as revealed by the contemplation of Cézanne and Goa Xi—illuminates both the European and the Chinese approach to nature, the one through a momentary bodily feeling, the other through an eternal spatial unity. But the ever beautiful of both—if we believe in their inherent message to us—is under threat today. Thus, not only the culturally limited but also the interculturally possible experience of art opens up ways of connecting people to nature.[33] These examples alone are promising for intercultural connections and understanding and also for the reevaluation of the interaction between humans and nature.

Martina Sauer

msauer@bildphilosophie.de

Martina Sauer runs the Institute of Image and Cultural Philosophy in Bühl (Baden), Germany ( HYPERLINK https://www.bildphilosophie.de/en-gb). She is a senior editor of Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine and a scientific advisor of the Society of Interdisciplinary Image Science (GiB) and the German Society of Semiotics (DGS). In the latter, she heads the image section. She was a scientific associate in philosophy of art and culture, aesthetics, and design in Basel, Zürich, Bremen, Witten and a scientific associate at Bauhaus-University Weimar. Currently, she holds seminars on the fundamentals of perception and design at the Fresenius Hochschule, University of Applied Science, Academy Mode & Design in Düsseldorf and Berlin University of the Arts. See also ORCID: 0000-0002-4787-3189.

For further publications, see: arthistoricum.net, researchgate.net, academia.edu, philpeople.org.

Published on December 10, 2024.

Cite this article: Marina Sauer, “Vitality Semiotics: The Ever Beautiful and Its Potential for an Intercultural Approach,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 12 (2024), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] Sabine A. Döring, “Ästhetischer Wert und emotionale Erfahrung,“ (“Aesthetic Value and Emotional Experience,“ trans. Martina Sauer) in eds. Julian Nida Rümelin and Jakob Steinbrenner, Kunst und Philosophie, Ästhetische Werte und Design (Ostfildern: Cantz, 2010), 53-73.

[2] Martina Sauer, Faszination—Schrecken. Zur Handlungsrelevanz ästhetischer Erfahrung anhand Anselm Kiefers Deutschlandbilder (Fascination—Horror. On the Relevance of Aesthetic Experience for Action on the Basis of Anselm Kiefer’s Pictures of Germany, trans. Martina Sauer), 2012 (Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2018), 19-30, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.344.471.

[3] Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, 1915, trans. M.D. Hottinger (New York: Dover, 1950), accessed August 14, 2024, https://archive.org/details/princarth00wlff.

[4] Lambert Wiesing, The Visibility of the Image. History and Perspectives of Formal Aesthetics, 1997, 2nd. ed., trans. Ann Roth (New York & London: Bloomsbury, 2016), introduction and ch. 3.

[5] Daniel N. Stern, The Interpersonal World of the Infant (New York: Basic Books, 1985), 157-161, and also Daniel N. Stern, Forms of Vitality Exploring Dynamic Experience in Psychology, Arts, Psychotherapy, and Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). Cf. with regard to Susanne K. Langer, Philosophy in a New Key. A Study in Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art, 1942, 6th ed. (New York: American Library, 1954). Cf. also Martina Sauer, “Entwicklungspsychologie, Neurowissenschaft und Kunstgeschichte – Ein Beitrag zur Diskussion von Form als Grundlage von Wahrnehmungs- und Gestaltungsprinzipien.“ (“Developmental Psychology, Neuroscience and Art History – A Contribution to the Discussion of Form as the Basis of Perceptual and Design Principles,” trans. Martina Sauer), Ejournal.net 6 (2011): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00003192.

[6] Stern, Forms of Vitality, 3-18. In this way, Stern follows up on Heinz Werner’s initial reflections, which also refer specifically to the arts. Cf. Heinz Werner, Comparative Psychology of Mental Development, 1926, adapted 1940, trans. Edward B. Garside. 2nd ed. (New York: International University Press, 1957), 71-72, accessed August 14, 2024, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.138929/page/n11/mode/2up. Werner´s approach was developed in the so-called Hamburg Circle in Germany around the philosopher Ernst Cassirer. See for this connection Ernst Cassirer, An Essay on Man. An Introduction to a Philosophy of Human Culture, 1944 (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1953), 176-217. Also of interest here is that the latter was associated with Susanne K. Langer.

[7] Cf. Martina Sauer, “Ästhetik und Pragmatismus. Zur funktionalen Relevanz einer nichtdiskursiven Formauffassung bei Cassirer, Langer und Krois,” (“Aesthetics and Pragmatism. On the functional relevance of non-discursive conceptions of form in Cassirer, Langer and Krois,” trans. Martina Sauer) Image 20 (2014): 49-69, and Martina Sauer, “Towards Vitality Semiotics and a New Understanding of the Conditio Humana in Susanne K. Langer,“ in ed. Lona Gaikis, The Bloomsbury Handbook of Susanne K. Langer (London: Bloomsbury, 2024), 223-238: https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350294660.ch-15.

[8] Martina Sauer, Cézanne, van Gogh, Monet. Genese der Abstraktion (Cézanne, van Gogh, Monet. Genesis of Abstraction, trans. Martina Sauer), (PhD diss., University of Basel, 1998), 157-209, https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00002573.

[9] Martina Sauer, “From Aesthetics to Vitality Semiotics – From l´art pour l´art to Responsibility. Historical change of perspective exemplified on Josef Albers,“ in eds. Lars C. Grabbe, Patrick Rupert-Kruse, and Nobert M. Schmitz, BildGestalten. Topographien medialer Visualität (Büchner: Marburg, 2020), 185-205, https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00007276.

[10] Sauer, Faszination—Schrecken.

[11] Döring,“Ästhetischer Wert und emotionale Erfahrung,“ 60-71.

[12] Sabine A. Döring and Christopher Peacocke, “Handlungen, Gründe und Emotionen,“ (“Actions, Reasons, Emotions,“ trans. Martina Sauer), in eds. Sabine Döring and Verena Mayer, Die Moralität der Gefühle (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2002), 92. For the history of this approach in neuroscience and developmental psychology, see also the chapter in the same anthology, 39-57, here 41, by Thomas Goschke and Annette Bolte, “Kognition und Intvc uition: Implikationen der empirischen Forschung für das Verständnis moralischer Urteilsprozesse” (“Emotion, Cognition, and Intuition: Implications of Empirical Research for Understanding Moral Judgment Processes,” trans. Martina Sauer).

[13] On the beginnings of formal aesthetics in the nineteenth century cf. Martina Sauer, “Debatte zwischen spekulativer Ästhetik und Ästhetik als Formwissenschaft,“ (“Debate between speculative aesthetics and aesthetics as a science of form,” trans. Martina Sauer), in ed. Gerald Hartung, Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, vol 1/2. Die Philosophie des 19. Jahrhunderts (Basel: Schwabe, 2023), 425-447, 2nd ed. 2024: https://doi.org/10.11588/

[14] Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, 12.

[15] A first exemplary detailed analysis and evaluation can be found in Sauer, Cézanne, van Gogh, Monet, 110-156.

[16] Cf. Wiesing, The Visibility of the Image, introduction.

[17] Sauer, Faszination—Schrecken, 19-29.

[18] On this phenomenon, see the collection of essays in eds. Martina Sauer and Zhuofei Wang, Atmosphere and Mood. Two Sides of The Same Phenomenon, special issue, Art Style 11 (2023), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7654767.

[19] Stern, The Interpersonal World of the Infant, 27-28, elaborated 162-182.

[20] Stern, Forms of Vitality, 3-18.

[21] Stern, The Interpersonal World of the Infant, 47-68; 51.

[22] Stern, Forms of Vitality, 75-98.

[23] Stern, The Interpersonal World of the Infant, 157-161.

[24] Ibid., 28.

[25] Cf. Sauer, Faszination—Schrecken, 107-90.

[26] Giacomo Rizzolatti et al., “Action recognition in the premotor cortex,“ Brain 119 (1996): 593-609.

[27] Giuseppe Di Cesare et. al., “The Neural Correlates of ‘Vitality form’ Recognition: An fMRI Study,” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 9, 7 (2013), 951-960: https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst068.

[28] Giuseppe Di Cesare, Marzio Gerbella, and Giacomo Rizzolatti, “The neural bases of vitality forms,” National Science Review 7 (2020): 202–213, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwz187.

[29] Giada Lombardi and Giuseppe Di Cesare, “From Neuroscience to Art: The Role of ‘Vitality Forms’ in the Investigation of Multimodality,” in eds. Martina Sauer and Christiane Wagner, Multimodality: On the Sensually Organized and at the same Time Meaningful and Socio-culturally Relevant Potential of Artistic Works, special issue, Art Style 10 (2022), 11-23, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7020465.

[30] Cf. for this the current joint research from neuroscience and image science of Giada Lombardi, Martina Sauer, and Giuseppe di Cesare, “An Affective Perception: How ‘Vitality Forms’ Influence our Mood,“ in eds. Martina Sauer and Christiane Wagner, Multimodality: On the Sensually Organized and at the Same Time Meaningful and Socio-culturally Relevant Potential of Artistic Works, special issue, Art Style 11 (2023), 127-139, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7651433.

[31] Max Imdahl, “´Wilde Ontologie´- Ästhetische Kohärenz,“ (“´Wild Ontology´- Aesthetic Coherence,“ trans. Martina Sauer), in Kunstchronik 38 (1985), 117, cf. Sauer, Cézanne, van Gogh, Monet, 61-62 and 75-76.

[32] Zhuofei Wang, “At Atmosphere and Moodmospheric: Fusion of Corporeality, Spirituality and Culturality,” in eds. Martina Sauer and Zhuofei Wang, Atmosphere and Mood. Two Sides of The Same Phenomenon, special issue, Art Style 11 (2023), 9, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7647600.

[33] Cf. Martina Sauer, “Interaction of Nature and Man after Ernst Cassirer: Expressive Phenomena as Indicators,“ in eds. Jacobus Bracker and Stefanie Johns, Critical Zone, special issue, Visual Past 7 (2023), 147-161, https://doi.org/10.11588/artdok.00008340.