The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

Is Generative AI in Aesthetics Really New?: The Visualist Perspective

Michalle Gal

Abstract

The concept of AI in aesthetics is encountering interest as new algorithmic machines now generate visual works alongside philosophical discourse, sparking both enthusiasm and concern. Yet, this idea has deep roots, reflected in longstanding debates within the discipline. These discussions, which are similar to the new ones, have examined issues like the illusion of an image or object’s ontological stability; the nature of function and user control; distinctions between the natural and artificial, authenticity and forgery; the divide between handmade and mass-produced items; the challenges of readymade and indiscernibility in art; and the potential of ekphrasis. As a result, skepticism emerges toward claims about an essential transformation in the field of aesthetics. The essay presents the claim that this dialectic structure of newness, which reveals sameness in our being as exposed by aesthetic AI, can be well explained by what I name ‘visualism.’ Visualist philosophy characterizes us as primarily constituted by external-visual ontology and experiences, rather than by well-ordered rational and conceptual schemes. Visualism follows the visual turn that identifies the dominance of the visual sphere as the proper field for studying our essence, ontology, and culture. Accordingly, I argue that generative aesthetic AI is naturally subsumed under what visualism identifies as the essence of the visual—its resonant vitality and the always-emergent properties and affordances of visual artifacts, be they art, design, or any sort of imagery, that cannot be preconceptualized or planned from the outset.

Key Words

AI; AI image generators; design; emergent properties; formalism; machine; mass production; readymade; visualism

1. Introduction

In this essay, I aim to provide a philosophical framework of generative artificial intelligence (AI) imagery in relation to aesthetics. I characterize it as deeply rooted in aesthetics, both in theory and practice, making it intrinsic to human nature, if we accept that aesthetics is essential to us. In other words, its artificiality is natural to us. My general meta-aesthetic claim is that generative AI does not dramatically change the field of aesthetics. Rather, it exposes a continuity of the aesthetic discourse that stems from the character of the visual sphere and us as visual beings. I ground this proposition in the nature of the visual sphere, our visualist nature, and the resulting continuing themes that have been discussed in academic aesthetic discourse for many decades.

Generative visual artificial intelligence employs algorithmic generative models to produce visual imagery, media, and artifacts. It is a subdivision of artificial intelligence, whose emergent visual output is dependent on a visual database gathered and classified by machine learning and is generated in reaction to prompts or language-based orders that are given by the user. Using the visual database, generative AI can produce various versions, modifications, or combinations of existing original images, details, and parts of images, including elements such as style, theme, and cultural contexts. It is a practice that is continuously expanding due to its inherent structure. The rapid rise of generative AI in visual creation has raised significant concerns within the field of aesthetics about its potential to displace authentic imagery, visual art, and design, in addition to aesthetic creativity and its process. Since AI is now capable of generating complex and varied images quickly, accurately, and stylishly, traditional views and aesthetic theories of image-making, art, and design as inherently human forms of creativity are being challenged. These issues touch on central topics of aesthetic inquiry. Consequently, there are concerns about how this technology of prompted algorithmic work may disrupt creative disciplines and change the way philosophy, critics, and viewers evaluate visual media, its expressivity and authenticity, and the human creative process in general.

However, I claim that visual generative AI does not conclude the field of aesthetics as we understand it, nor does it usher in a completely new phase. Instead, it demonstrates an underlying human sameness and fundamental similarity among philosophical themes: a dialectic between newness and sameness that has surfaced in numerous established philosophical discussions. This will be offered through a theory that I call ‘visualism’—a theory that points to the generative essence of the visual sphere, namely, to visuality’s natural ongoing emergence, and its constitutive role in shaping our identities, conducts, and even mental schemes.[1] I will seek to prove the following proposition: Despite the engineered quality of generative AI and its seeming detachment from human touch, it embodies a distinctly natural, essential quality of us as active perceivers and of our relations with the visual sphere. The newness of its mechanism of production actually reflects a fundamental sameness within our existence. In this sense, generative aesthetic AI aligns with visualism’s characterization of the visual—the inherent vitality and ever-flowing emergent properties of visual artifacts, whether in art, design, or imagery. These qualities defy preconceptualization, resisting strict planning or control. The visual sphere has always been unruly at times, as specifically demonstrated now by generative AI, but perhaps that is where its richness lies.

Visualist philosophy is based on externalism, suggesting that we are primarily constituted by external visual experiences, rather than well-structured, stable, rational, and conceptual schemes. My contention is that we are sensuous beings primarily governed by visual perception. I follow propositions like those presented by Rudolf Arnheim in his seminal Visual Thinking, that our cognition resides and evolves within external perceptual compositions and activities.[2] I, therefore, also join voices such as Kristof Nyíri’s, who elaborates on Arnheim’s approach to support the twenty-first-century’s visual turn. Nyíri asserts that “the human mind is a visual one” and argues that what he refers to as “the visual approach” should be more accepted within mainstream philosophy.[3] Against internalism and conceptualism, which typify our engagements with the world as guided by stable conceptual schemes, visualism claims that our engagements with the world mainly originate in the visual sphere and that we tend to have creative and resourceful engagements with it.

The current expansion of focus on the visual is based on the recognition that in an age dominated by interfaces, screens, social media, and an overwhelming amount of imagery—including images generated by AI—we can emphasize the importance of the visual realm for understanding our nature, existence, and culture. I therefore seek to articulate that the concept of visualism—the premise that our motivations are more significantly influenced by external visual appearances than by organized internal frameworks—provides a valuable lens through which to understand our interactions and responses to images and works of art or design, regardless of whether they are created by artificial intelligence or by human hands. To summarize the line of thought presented so far, and which will be further illustrated and exemplified, visualism can explain the naturalness of generative artificial intelligence due to two main features.

a. Visualism stresses the emergent, unpredictable, and always effervescent essence of the visual field, and this essence’s significance in our nature, culture, and ontology. Due to its affordances and power, visuality, so to speak, invites new uses and engagements.

b. Visualism emphasizes the significance of re-uses and new interactions, both in everyday life and creative practices, as essential to our nature. This perspective highlights how existing materials always have been constantly engaged for new properties to emerge, leading to novel classifications of familiar images and objects. They thus ultimately generate new forms that are based on older ones: the new ones are rooted in past creations, styles, themes, modes of presentations or compositions.

2. Generative natural visual

A suitable vantage point for the account of aesthetic AI is the paradigmatic phenomenon in design of the variety of emergent uses that a form in design may afford.[4] The type of interaction between children and stairs, where they use the stairs as benches and gathering spots rather than merely climbing to the attached building, is very common and paradigmatic. This behavior reflects our natural tendencies and the visual affordance of the stairs (Figure 1).

Think about the various emergent uses and engagements that the visuality of almost every single object and image in our environments invites: chairs as ladders, fences as benches, colanders as makeshift hats in kid’s games, refrigerators’ fronts as notes boards—the number of examples is immeasurable because there is “almost limitless functions to which a single form can lead,” as Henry Petroski points out in his The Evolution of Useful Things. He informs, for example, that a study found out that “only one in ten paperclips was ever used to hold papers together. Other uses included “toothpicks; fingernail and ear cleaners; makeshift fasteners for nylons, bras, and blouses; tie clasps; chips in card games; markers in children’s games; decorative chains; and weapons.”[5]

James Gibson coined the term ‘affordance’ to the various engagements, complementary relations, and uses those things or environments allow or offer us. In his seminal book, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, he argues that visual surfaces contain both the knowledge of the planned function or classification of a thing and all the possible functions and meanings that might emerge from it.[6] Following Gibson, one may claim that philosophy, ontology, and theories of human nature should not address the phenomenon of emergent uses lightly. This omnipresent phenomenon comprises the topic of this significant field: visuality generated by artificial intelligence, that is, a variety of algorithms and platforms engineered both for deep learning and generative techniques, to analyze vast databases, learn patterns and styles of existing visual materials, and produce new ones. The humdrum phenomenon of the constant emergence of engagements and properties of objects in our environments—of the generative everyday visuality—is structurally parallel and somewhat equivalent to generative AI imagery. It may be a simpler version of AI. However, it implies that generative AI is not a foreign mechanism, but rather is natural to our engagement with the visual.

Now, the stairs’ post-production emergent property of being used as a bench or a gathering spot is as significant and often well-established as the preproduction planned property of being climbed. Therefore, this emergent use, generated by the visual affordance of the stairs, is as authentic as the intended use. And what about a chair used as a clothes stool, a makeshift leader, an exercise tool, or an element in an artwork such as Erwin Wurm’s Away From Home (2023) (Figure 2)?

Is seatability, namely, serving as a seating tool, more substantial or authentic than the chair’s emergent encounters? I believe the answer is “no.”

Indeed, the design piece was carefully planned, and accordingly prevailing aesthetic theories define the design object as being based on rationality and ontologically stable. ‘Ontological stability’ means that these objects maintain their identity, or category, even when they are reused or even repurposed.[7] The stability of design objects has been recently advocated for by Jane Forsey in her theory of appreciation of design, which claims that “uses to which an object may be put, no matter by how many or how frequently, do not have the ability to alter its ontological status as being a thing of a certain kind.”[8] Moreover, current conceptualist-rationalist design theories, formulated for example by Donald Norman and Glenn Parsons, define design as linearly advancing from the rational plan of a proper function to a fitting object, and then to the proper use or engagement with the user.[9] These originate in Plato’s teleology, manifested in Republic Book 10, as follows “the goodness, beauty, and correctness of any manufactured object, living thing, or action are entirely a question of the use for which each of them made.”[10]

Accordingly, in his essay, “Affordance, Conventions, and Design,” Donald Norman, mistakenly, I claim, narrows the concept of affordance originally proposed by Gibson to refer only to the proper use of a design object that aligns with its conceptual plan. He claims that “the most important design tool is that of coherence and understandability, which comes through an explicit, perceivable conceptual model.”[11] Along this line of thought, Parsons claims in his 2015 book, Philosophy of Design, that the plan, the meant use, determines the object’s ontological identity: “The concept of design, it seems, entails a certain kind of rational connection between the final product and the creative process: if a person designs an X, then the creation of the plan for X is guided by the goal of producing something that can do what X does.”[12] Parson specifies that unplanned results of the design object, even valuable ones, do not belong to its ontological identity. Both Norman and Parsons miss the independent power of visual works and our creative tendencies when engaging with them.

However—and this is a significant point—theories of ontological stability do not coalesce with both the emergent power of the visual sphere and our natural and forceful active perception. Objects often generate numerous post-production emergent uses, serving as readymade elements for new pieces—and this generative character is an essential part of their being and our relations with them, which Gibson describes as “complementarity between seeing the layout of the environment and seeing oneself in the environment.”[13] I agree with David Pye’s assertion in The Nature and Aesthetics of Design that the pre-planned “function is a fantasy.” He states that function is actually “what someone has provisionally decided that a device may reasonably be expected to do at present.”[14] Judith Attfield rightfully presents in her Wilde Things: The Material Culture of Everyday Life a similar critique of design theories and practices, which have always been under the illusion of the ability to control the engagements with design objects. Attfield’s critique brings us even closer to generative AI, because she refers to theories that rediscover the power of the object themselves, in light of the rise of “‘artificial reality’ generated by the technology of a post-industrial society.”[15] Nowadays, Attfield claims, in the age of artificial intelligence, philosophers of design are willing to let go of the illusion of the concept of the product, finally realizing the ability of “the user to enter into the creative act of designing.”[16]

Then again, I would like to emphasize that the user’s creative act of redesigning the design object has always been evident—in everyday engagements with the visuality of objects. Therefore, visualism refutes the claims for the object’s stability, and accordingly defines the object as an open space for generated uses.

While research on active visual perception is current, to support my point about sameness and continuity, which influence the continuity of the academic aesthetic field and also its themes and structures of controversies, I want to highlight the extensive studies conducted before the advent of visual generative AI. Already in the 1960s and 1970s, James J. Gibson, Rudolph Arnheim, Ernst Gombrich, and Nelson Goodman, all prominent aestheticians, opposed the notion of an “innocent eye” because “the eye comes always ancient to its work, obsessed by its own past.”[17] These theories prove the naturality of the mechanism of generative AI in addition to the use of visual storage. These aestheticians formulated theories of active perception, where perception and projection are intimately connected to the object or image’s affordance and properties that can be imagined or made to acquire or generate. As visualists, they made significant strides in an era largely dominated by conceptualist thought. One may say that their pioneering visualist theories paved the way for the current visual turn. By recognizing the integral role of the visual realm in our existence and acknowledging our inherently visual nature, they extended theories of cognition and thinking toward externalist perspectives and proposed a constructivist view of perception.

Gombrich’s theory of active perception and representation in Art and Illusion is famously reviewed by Arnheim, who observes that the fundamental burden placed on the observing eye is culturally influenced, making the source of representation inherently external—shaped by education, conventions, habits, and history. He suggests that mental frameworks are formed by their era:

Gombrich is not mainly interested in the goal of pictorial representation but rather in the ways it is accomplished. In his opinion, representation becomes acceptable when it fits the schemata of realization to which the perceiver is accustomed. The artist paints what the reservoirs of his experience offer him as the proper form for his subject. These reservoirs contain the schemata supplied by the artist’s teachers and by other models of the past. Beyond that, they equip him with the expectations necessary to see anything at all: We see what we assume is ‘out there.’[18]

The visual reservoirs combined with the object’s visuality afford the ongoing emergence of properties and engagements of users with its surface, which were not, could not, be preconceptualized or planned. Inherently related to it is the visual metaphor that is also ever-present and innate to us as visual beings. The visuality of the banana is used to reconstruct the Zhedony (2005) banana chair, generating emergent properties that can be owned only by the banana chair (Figure 3).

The visuality of the banana may serve as a source for a coin purse or a pen case (Figure 4)

or Banana Ski Hill Jumping (2024) by Tatsuya Tanaka, who is known as the “artist of mitate,” which is the Japanese word for “to look again” and explained as “seeing or using something old in a new way or as something else” (Figure 5).

Gombrich argues that metaphor functions as a projection of intended functionality onto an object, transforming it into something else—be it a color stain that becomes a horse image, a stick that turns into a hobby horse, or even a snowman or sculpture. This act of projection relates closely to the schemata that shape both eye and mind, which may originate in a blend of external, intrasensory, primordial, material, and perceptual influences. I take it further to claim that visual metaphors create new ontological structures and enhance categories. Moreover, using the source to reconstruct the visual target anew naturally creates a mechanism of emergent properties, that could not be pre-conceptualized or planned because they result from the autonomous power of the visual metaphoric composition.[19]

This structure of seeing and using something old in a new way is similarly demonstrated in what I label as “passing metaphors,” which demonstrate our natural aesthetic-visual tendency to reorganize and reconstruct daily percepts as well as the generative quality of the visual sphere.[20] I elaborate here on Gombrich’s emphasis on the natural perceptual tendency to merge categories and see the regular elements in the visual environment as expressive. He explains, in “On Physiognomic Perception” from 1960, that “it adds to the interest of these categories that they are so often intrasensory: the smile belongs to the category of warm, bright, sweet experiences; the frown is cold, dark, and bitter in this primeval world where all things host.”[21] Passing metaphors are generated, for example, by our predisposition to provisionally apply faces and various shapes to everyday things like clouds, sockets, or approaching car lights, creating the illusion that the car is staring at us.

I think that these phenomena of creatively engaging, reusing, reconstructing, and reclassifying visual things emanate from our attachment to forms and the role they play in our lives. Visual forms are passed down through generations, treasured, referenced, and echoed. They are repurposed, offering joy and comfort, borrowed or replicated, and layer by layer they contribute to building cultures. They shape thoughts, ideas, and ideologies, and enrich our ontological experience. The sense of nostalgia triggered by the disappearance of iconic objects like the pocket radio, vintage television, or rotary dial phone, and the contrasting pleasure of seeing these forms reimagined or unexpectedly incorporated into new designs, are familiar to many. Alongside this is the widespread appreciation for innovative forms. Forms and their styles are continuously referenced and reinterpreted across art, every design discipline, and even in the aesthetics of daily life, extending to the most ordinary visual elements that shape our everyday surroundings.

This omnipresent phenomenon of generated uses and emergent properties sheds light on the dialectic structure of AI and its associated philosophical discourse. We can summarize the aforesaid by three critical points revealed by this phenomenon:

a. The fiction or illusion of the stability of the object or the image has put rationalist ontologies of artifacts under its spell.

b. The instability of objects and images is a result of the visual sphere being essentially generative, powerful, and ever-dynamic.

c. We are creative visual beings ourselves, employing active perception and emergent engagement with the visual sphere.

Therefore, I would like to claim that in the framework of visualism aesthetic AI is merely one more practice that engages us, visual beings, with visual ontology. Generative artificial intelligence is as natural as it is artificial. After all, we see that time and again, in everyday moments as well as artistic heights, we employ the visuality of things, sometimes of well-planned and complete artifacts, as readymades for making new things. Aesthetic AI is subsumed under this praxis because it helps us to create images, and soon objects, I am sure, using existing materials and friendly interfaces in everyday actions and in design or art.

It is often claimed, for example just recently in Medium Magazine, that the visual AI generator, this data-trained algorithm, challenges the established status and authorship of the artist or designer and the very idea of authenticity.[22] But the same challenge is set by the various everyday uses of stairs or chairs. These uses have nothing to do with the proper function that was pre-planned by the designer; rather, they introduce the object to a whole new category. We will soon see that similar concerns about authenticity have been raised also due to mass production, reproductions, quotes, collages, and ready-mades, or visually indiscernible works. We will see that these philosophical discourses have been present for a long time.

Claims about AI transforming quantity into quality are also heard frequently these days. For example, in his book, AI Aesthetics, Manovich claims that while the integration of algorithms in art has been practiced since the 1960s, presently “cultural AI” operates on an industrial scale and is utilized by billions.[23] He adds that this shift signifies a departure from individual artistic expression. By gathering and analyzing data on cultural behaviors, AI constructs a model of our alleged “aesthetic self,” enabling the prediction of future aesthetic preferences and potentially guiding choices toward the popular ones. This raises questions about the future of culture, aesthetics, and taste, according to Manovich. These are thoughts, or worries, about the quality effect of the very quantity of AI. However, I think that these premonitions underestimate the ever-significant impact of visuality on us since forever. As said, our eye is not innocent. This impact already comes along with all the biases, or pressures, which were called by the Arnheim “visual knowledge” and “norm images.”[24]

These concepts are closely linked to the critique of the innocent eye model famously challenged by Gombrich, and Goodman and Arnheim, who approach it from a visualist perspective. The structures that influence our vision stem from visual perception and our engagement with reality. It is important to note that these structures are prototypical. Arnheim, among others, argues that the value and impact of preexisting images rely not only on familiarity with prototype images but also on “what the nature of the given context seems to call for,” implying that “what one expects to see depends significantly on what ‘fits’ in that specific context.”[25] The perception or recognition of types is intrinsically linked to what Arnheim refers to as “norm images,” which are accumulated within the observer’s visual storage.

These ideas even come along with what Clement Greenberg called ‘traps’—a terminology he used to describe the power of the industry over visual culture in the 1930s.[26] See how Greenberg’s famous formulation of kitsch from eighty years ago can be applied to the current dynamic visual sphere, generated AI imagery included:

The precondition for kitsch… is the availability close at hand of a fully matured cultural tradition, whose discoveries, acquisitions, and perfected self-consciousness, kitsch can take advantage of for its own ends. It borrows from its devices, tricks, stratagems, rules of thumb, and themes, converts them into a system, and discards the rest. It draws its lifeblood, so to speak, from this reservoir of accumulated experience.[27]

Greenberg’s rejection of the method of borrowing from the “reservoir of accumulated experience” is unfounded, disregarding the vitality and incredible potential of visual culture. Much of visual culture evolves through transitions between visual pieces using the methods mentioned above. Yet, it also proves that the basic core of generative AI is not new and is essential to visual culture. Greenberg’s critique also exemplifies the ongoing concerns in aesthetics that were repeatedly caused by forceful methods in the visual field that could trigger a paradigmatic shift in art, design, and philosophy. I will return to these worries shortly.

At this stage, I want to stress the following: As forceful and manufactured as generative AI is, and notwithstanding its distance from the touch of the human hand, it is also very natural. Its dialectic structure of newness highlights the sameness of our being. Therefore, one may argue that generative aesthetic AI naturally falls under what visualism identifies as the essence of the visual—its vibrant vitality, the always-generated properties of visual artifacts, whether it is art, design, or any form of imagery. These properties cannot be preconceptualized, planned, or controlled from the outset. True, the visual world, with our assistance, tends to blend and untangle categories. It is therefore sometimes unpredictable, dynamic, and even messy. But it is not necessarily a bad thing.

3. Parallel debates in aesthetics

The claim about the naturalness of generative artificial intelligence can also be supported by pointing out that the structure of the polemics about generative AI can be traced back to earlier moments in philosophy and aesthetics. To be precise, the dialectic of newness which reveals sameness by aesthetic AI is accessible through previous debates in the field. These are related to the aforementioned topics of visuality and perception that have always occupied aesthetics. I will highlight a few debates as typical examples of many additional ones.

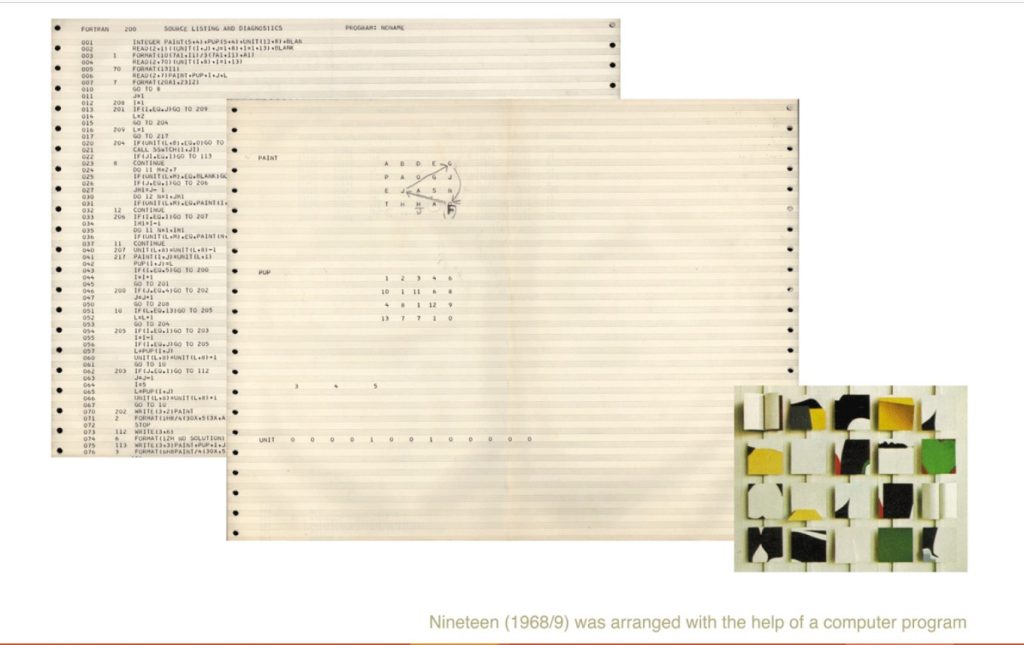

First, it is well known that self-conscious, computer-produced art has been around since the 1960s, followed by a theoretical study. Already in 1973, the artist and theoretician Ernst Edmonds, one of the leading inventors of computer, algorithmic, and generative art, co-wrote with Stroud Cornock an article titled “The Creative Process Where the Artist Is Amplified or Superseded by the Computer.”[28] They reported about “the retreat from the number of specifically human characteristics and functions by which we define ourselves.”[29] In a 2019 paper, “AI, Creativity, and Art,” Edmonds says, “I was very interested in computer-based artworks that were themselves open systems.”[30] Edmonds revisited his work, “Nineteen,” from 1968 and 1969 (Figure 6)

in the catalog of his 2014 show, Creative Machine: “I used a computer program to help me determine which piece went where. I specified a set of conditions… and the program searched all possibilities for a solution.” He adds, “Once programming became used in art, the art now known as ‘Generative’ appeared.”[31]

A philosophical examination of our nature and ontology in this case shows that technological tools and new possibilities frequently reintroduce the dialectical relationship between newness and its perceived opposite, that is, the continuity of our humanity, namely, the lines of ideas, conducts, and motivations that have accompanied us since antiquity. Let us look at long-established philosophical debates that are structurally parallel to the ones currently revolving around generative AI that, as I see it, address the following three interrelated topics:

-

The contrast between authenticity and artificiality. This is initiated by the move beyond the concept of what is real and true, a growing disconnect between human craftsmanship and machinery, and worries about the fragile status of human handwork.

-

The question of the ontological stability of the object, artifact, or image.

-

Concerns about losing control and order in the visual realm and culture.

Given that the three points are innately connected, I will provide examples encompassing more than one. Cornock and Edmonds pointed out in 1973 that the anticipation of machine cognition spread an underlying note of fear throughout twentieth-century literature. They predicted that the sympathy for the artwork would be “proportional to the degree to which control is direct and personal; the master potter would be at one end of this scale, the sculptor who delivers telephone instructions for the fabrication of a sculpture to an engineering firm at the other. It is against this background that the machine threatens to usurp the essentially human function of control of making art works.”[32]

This range of “sympathy for the artwork,” which actually has been discussed since antiquity, is indeed evident nowadays too. It introduces conflicting opinions regarding the potentially harmful or beneficial impacts of generative AI imagery on aesthetics, contrasting the value of personal and handmade creations with that of engineered and machine-made works. For example, from one pole of the range, Craig Vear, the editor of The Language of Creative AI: Practices, Aesthetics, and Structures from 2022 says that he feels as if the AI generator is a real collaborator. He calls the reader to “examine artistic structures that emerge from the use of computers not only as a technical instrument but as a creative partner,” which “helps to expand the universe of the artistic language.”[33] From the other pole, and against this anthropomorphic view of the artificial generator of images, in their paper, “What is artificial about artificial intelligence? From 2024, Thomas Dekeyser and Mark Whitehead challenge the very classification of artificial intelligence as artificial, predicting that it “may come to be seen as a category mistake by future generations of scholars.” They therefore suggest the term ‘augmented Intelligence’ instead. According to Dekeyser and Whitehead, humans are “naturally” artificial, and the term ‘artificial’ simply means to be human-made, while what is referred to in the common use of ‘artificial intelligence’ goes beyond humanity. They explain that “a defining aspect of ‘artificial’ intelligence is its ability to work independently of human supervision, even if it can only ever be produced, judged and evaluated on the basis of presumably human criteria (brain, intelligence). To be artificially intelligent is, then, first and foremost, to be non-human.”[34] AI frequently operates on the assumption that humanity exists apart from its technological counterparts. They thus point to philosophers such as Bernard Stiegler, who challenge this view by suggesting that humans are fundamentally interwoven with technology. Indeed, this idea has appeared in the literature. Bruno Latour’s renowned actor-network theory, first introduced in the 1980s, claims that there is symmetry between humans and nonhuman elements within the social sphere. Highlighting the mutual influence between technology, objects, and social connections, it demonstrates that design objects actively participate in shaping everyday interactions and their various possibilities.[35] Both these older and newer ideas blur the line between natural and artificial intelligence, as intelligence—whether mental or worldly—is inseparable from technological forms of expression like language, writing, and media.

A classification of generative AI imagery as antihuman has been presented by Miyazaki in the documentary film, Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki (2016). In this film, he is seen reacting to a demo of an AI-generated animation as follows: “I am utterly disgusted. If you really want to make creepy stuff, you can go ahead and do it. I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work at all. I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.” Realizing that the animators’ goal is to create a machine that “draws pictures like humans do,” Miyazaki adds: “I feel like we are nearing the end of the times. We humans are losing faith in ourselves.” A similar view of generative AI as an attack on humanhood has been expressed by the artist and writer Joanna Maciejewska through a tweet, posted in 2024, that garnered millions of views:

You know what the biggest problem with pushing all-things-AI is? Wrong direction. I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes… Just to clarify, this post isn’t about wanting actual laundry robots. It’s about wishing that AI focused on taking away those tasks we hate (doing taxes, anyone?) and don’t enjoy instead of trying to take away what we love to do and what makes us human.[36]

This very gap between treating the machine that produces visual artifacts as an authentic collaborator, or alternatively as a foreign tool that separates us from ourselves, has been discussed throughout lines of aesthetic thoughts for a long time. See the similarity between the current voices presented in the paragraphs above to those that surrounded the topic of mass production at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. In his known essay, “The Lesser Arts” from 1877, William Morris, a prominent aesthetician, artist, and designer, and leader of the Arts and Crafts movement and owner of a furniture factory, went against mass production, worrying about the loss of the authenticity and therefore the quality of visual aesthetic artifacts. He accordingly called for the unification of design and fine art lest designers find themselves “working helplessly among the crowd of those who are ridiculously called handicraftsmen, though they never did a stroke of hand-work in their lives, and are nothing better than capitalists and salesmen.”[37] Similarly, in 1912, the famous aesthetician, artist, designer, and curator Roger Fry, who was a member of the Bloomsbury Group, with the known formalist Clive Bell, expressed in a catalog of an exhibition of the Omega Workshops he ran his concern about the impact of mass production on art and design. Fry draws a clear distinction between what he names “real art” and “the humbug of machine-made imitation of works of art.” According to Fry, “Pottery is essentially a form of sculpture, and its surface should express directly the artist’s sensibility both of proportion and surface.” However, the direct expressiveness of surface modeling of dishes was lost as a result of “the application of scientific commercialism,” causing our cups and saucers to be “reduced by machine turning to a dead mechanical exactitude and uniformity.”[38] Both Morris and Fry, then, classified mass-produced works as devoid of the human foundations of art and design—a classification based on properties also attributed to generative AI.

A critical review of Fry and Morris, “who thought of industry as something inconsistent with art, and which must therefore be reformed or abolished,”[39] was presented by Herbert Read in his seminal Art and Industry from 1935. Read welcomed the collaboration between art, design, and industry renouncing “the conception of art as something external to industry, something formulated apart from the industrial process.”[40] His claim was that beauty and expressivity can be maintained by machine-mass-produced works. Similarly, the known theoretician and designer Bruno Munari, in his 1966 book, Design as Art, claimed like Morris that design and art should be unified, but for the opposite goal than the one set by Morris: to allow the mass-machine-produced works to bring beauty to every single home—“Instead of pictures for the drawing-room, electric gadgets for the kitchen.” The reason Munari supplied for his imperative is the need to assimilate art into the current material culture and society. “Culture today is becoming a mass affair, and the artist must step down from his pedestal and be prepared to make a sign for a butcher’s shop (if he knows how to do it). The artist must cast off the last rags of romanticism and become active as a man among men, well up in present-day techniques, materials and working methods.” Like Read, Munari stresses that the artist can do so, “without losing his innate aesthetic sense.” [41]

A concept similar to Munari’s call for decentralizing art and design is found in “Democratization and Generative AI Image Creation: Aesthetics, Citizenship, and Practices,” published in 2024. Munari emphasizes that every member of society can join the art and design community by owning well-designed everyday gadgets that serve as functional artworks. Similarly, “Democratization and Generative AI Image Creation” develops through an analysis of generative AI the “oxymoronic concept of ‘visual citizenship’ as a potential representation of belonging independent of any sovereign community, other than the aesthetic state as such.”[42] Following Jacques Rancière’s analysis of romanticism, which he used to promote the distribution of the sensible and dissolve the dichotomy between active understanding and passive sensibility, the authors hold a positive social perspective on aesthetics and generative AI as spreading out image-making and opening communities of visual citizenship. They believe that using generative AI may allow young people to engage in democracy by navigating and critically reflecting on modern visual culture, because “on the generative level, intentional creation and distribution of images contribute to public discourse… producing decentralized infrastructures that allow for many entry points for communities with various grades of technical knowledge.”[43]

The idea of visual citizenship naturally leads us to Arthur Danto’s theory of what he names “the artworld.” Danto’s intentionalist-conceptualist denunciation of the formalist theories formulated by Greenberg, Morris, Bell, and Fry is structurally parallel to current controversies about generative AI. In 1964, Pop Art artist Andy Warhol exhibited his Brillo Boxes, which looked exactly like their counterpart in the supermarket and were joined by the reemergence of readymade art. Doubts regarding their authenticity were answered in 1986 by Thierry de Duve’s contention that even the tube of paint had been considered readymade for Kandinsky, who formerly concocted his own paints. A further theoretical step was taken by Arthur Danto, one of the most important aestheticians in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Impressed by Warhol, Danto supplied a somewhat extreme take on the matter. Defining art as embodied meaning, he asserted that visually indiscernible artworks, such as exact replicas of existing artworks, could be different singular artworks if the artists’ intentions were different. Therefore, it is plausible to conclude that Danto’s aesthetics, first presented in his 1964 essay, “The Artworld,” would have endorsed the AI-generated images as long as they were preceded by clear intentions, meanings, or ideas. This can be supported by the various examples of visually (totally or partly) indiscernible works, whose identity is still different, that Danto presents in his following writings throughout the years. A paradigmatic one is Roy Lichtenstein’s Portrait of Madame Cezanne (1963), which copies Erle Loran’s diagram of Cezanne’s work in his book Cezanne’s Compositions. While Loran sued for plagiarism, Danto argues that Lichtenstein’s artwork is by no means a steal but an original thanks to the artist’s intention, namely because the artwork is based on intentionality. Danto informs us that “at that period Lichtenstein was ‘plagiarizing’ from all over: a picture of bathing beauty from an advertisement that stall appears for a resort in the Catskills.; various Picassos; and a number of things often so familiar that the charge of plagiarism is almost laughably irrelevant.”[44] Speaking about the artworld, we may close the circle with a recent article published in Medium Magazine, titled “The Aesthetics of AI-Generated Images,” which explains that “one argument against the complete integration of AI into the art world is the absence of intentionality. Human artists infuse their work with intention, purpose, and meaning, drawing from personal experiences and social contexts.”[45] Isn’t Danto’s theory helpful in addressing, maybe defying, this critique?

Danto is an intentionalist-conceptualist, and as a visualist I do not endorse his definition of art. However, its relevance to the contemporary debates about AI images supports what I have tried to point out. Visual AI generators are part and parcel of the natural emergent character of the visual sphere and our relations with it while naturally exercising our active perception. Generative AI engines open whole new horizons and at the same time own a deeply rooted known structure of natural visual creativity. The new kinds of possible activities and opportunities reveal that humanhood and the aesthetic discourse at least partially stay the same.

Michalle Gal

michalle.gal@shenkar.ac.il

Michalle Gal is a professor of philosophy at Shenkar. Gal is the author of Visual Metaphors and Aesthetics: A Formalist Theory of Metaphor (2022) Aestheticism: Deep Formalism and the Emergence of Modernist Aesthetics (2015), and Introduction to Design Theory: Philosophy, Critique, History and Practice (2023). She is the editor of the special issues Art and Gesture (2014,Paragrana, De Gruyter), Visual Hybrids (2024, Poetics Today) and Design and its Relations (2025), Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics)

Published on July 14, 2025.

Cite this article: Michalle Gal, “Is Generative AI in Aesthetics Really New?: The Visualist Perspective,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 13 (2025), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] Michalle Gal, Visual Metaphors and Aesthetics (London; New York: Bloomsbury Publication, 2022).

[2] Rudolf Arnheim, Visual Thinking (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), 13.

[3] Kristóf Nyíri, “Towards a Theory of Common-Sense Realism,” in In the Beginning Was the Image: The Omnipresence of Pictures, ed. András Benedek and Ágnes Veszelszki, Time, Truth, Tradition. New York; Bern: Peter Lang AG, 2016), 17, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2t4cns.4.

[4] Michalle Gal, “Design and Rationalism: A Visualist Critique of Instrumental Rationalism,” The Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics 47, no. 3 (2024): 75-76.

[5] Henry Petroski, The Evolution of Useful Things: How Everyday Artifacts-From Forks and Pins to Paper Clips and Zippers-Came to Be as They Are, Reprint edition (New York: Vintage, 1994), 52.

[6] James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition, 1st edition (New York London: Psychology Press, 2015).

[7] See Jane Forsey, The Aesthetics of Design, 1st Edition (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[8] Jane Forsey, “Design and Beauty: Functional Style,” Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics 58, no. 1 (2025): 38.

[9] Don Norman, The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition (New York: Basic Books, 2013); Henry Dreyfuss, Designing for People (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1974); Glenn Parsons, The Philosophy of Design (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015).

[10] Plato, The Republic, Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought (Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 321.

[11] Donald A. Norman, “Affordance, Conventions, and Design,” Interactions May-June (1999): 5.

[12] Parsons, The Philosophy of Design, 10.

[13] Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, 156.

[14] David Pye, The Nature and Aesthetics of Design (New York : Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1978), 12, 14, http://archive.org/details/natureaesthetics0000pyed.

[15] Judy Attfield, Wild Things: The Material Culture of Everyday Life, Materializing Culture (Oxford New York: Berg, 2000), 54.

[16] Attfield, 55.

[17] Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art, 2nd ed. (Indianapolis, Ind.: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1976), 7; E.H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Princeton, N.J. :Princeton University Press, 1969), 239.

[18] Rudolf Arnheim and E. H. Gombrich, “Art and Illusion. A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation,” The Art Bulletin 44, no. 1 (March 1962): 77, https://doi.org/10.2307/3047990.

[19] Michalle Gal, “The Visuality of Metaphors: A Formalist Ontology of Metaphors,” Cognitive Linguistic Studies 7, no. 1 (2020): 71, https://doi.org/10.1075/cogls.00049.gal; Gal, Visual Metaphors and Aesthetics, ch. 5.

[20] Gal, Visual Metaphors and Aesthetics, 23.

[21] E. H. Gombrich, “On Physiognomic Perception,” Daedalus 89, no. 1 (1960): 232-33.

[22] Satya @Top Trends, “The Aesthetics of AI-Generated Images: A Critical Examination,” Medium (blog), December 22, 2023, https://medium.com/@rohit017228/the-aesthetics-of-ai-generated-images-a-critical-examination-d787a75347bd.

[23] Lev Manovich, AI Aesthetics (Moscow: Strelka Press, 2018).

[24] Arnheim, Visual Thinking, 94.

[25] Arnheim, 94.

[26] Clement Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939-1944, ed. John O’Brian, Reprint edition, vol. I (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 13.

[27] Greenberg, I:12.

[28] Stroud Cornock and Ernest Edmonds, “The Creative Process Where the Artist Is Amplified or Superseded by the Computer,” Leonardo 6, no. 1 (1973): 11–16, https://doi.org/10.2307/1572419.

[29] Cornock and Edmonds, 11.

[30] Ernest Edmonds, “AI, Creativity, and Art,” in The Language of Creative AI: Practices, Aesthetics and Structures, Springer Series on Cultural Computing (Springer, 2022), 59.

[31] Ernest Edmonds, Atau Tanaka, and Frederic Fol Leymarie, “Creative Machine” (Creative Machine, Goldsmiths, University of London, 2014), 24, http://www.creativemachine.org.uk/.

[32] Cornock and Edmonds, “The Creative Process Where the Artist Is Amplified or Superseded by the Computer,” 11-12.

[33] Craig Vear and Fabrizio Poltronieri, eds., The Language of Creative AI: Practices, Aesthetics and Structures (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2022), xii.

[34] Thomas Dekeyser and Mark Whitehead, “What Is Artificial about Artificial Intelligence? A Provocation on a Problematic Prefix,” AI & SOCIETY, October 29, 2024, 1, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-02114-8.

[35] Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory, 1. publ. in pbk, Clarendon Lectures in Management Studies (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

[36] Joanna Maciejewska [@AuthorJMac], “You Know What the Biggest Problem with Pushing All-Things-AI Is?,” Tweet, Twitter, March 29, 2024, https://x.com/AuthorJMac/status/1773679197631701238.

[37] William Morris and May Morris, “The Lesser Arts [1877],” in The Collected Works of William Morris: With Introductions by His Daughter May Morris, Cambridge Library Collection – Literary Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 14, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139343145.003.

[38] “The Omega Workshop, Trade Catalogue c 1914,” 5, 10., accessed July 17, 2022, https://www.fulltable.com/vts/o/om/o.htm.

[39] Herbert Read, Art and Industry: The Principles of Industrial Design (New York: Harcort, Brace, and Company, 1935), 31.

[40] Read, 135.

[41] Bruno Munari, Design as Art (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1971), 20.

[42] Maja Bak Herrie et al., “Democratization and Generative AI Image Creation: Aesthetics, Citizenship, and Practices,” AI & SOCIETY, October 11, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-02102-y.

[43] Bak Herrie et al.

[44] Arthur Coleman Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art, Seventh printing (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1996), 142.

[45] Satya @Top Trends, “The Aesthetics of AI-Generated Images: A Critical Examination.” Medium (2023). https://medium.com/@rohit017228/the-aesthetics-of-ai-generated-images-a-critical-examination-d787a75347bd, accessed 2024-11-29.