The free access to this article was made possible by support from readers like you. Please consider donating any amount to help defray the cost of our operation.

On Deepfakes and Dog Whistles: Thinking Aesthetically about Generative AI

Maja Bak Herrie

Abstract

This article focuses on the aesthetic dimensions of contemporary media created with generative AI, challenging traditional dichotomies of truth and falsehood, real and fake. It draws upon diverse examples including Samsung’s “Space Zoom” images of the moon, AI-driven political imagery, and the randomized aesthetics of Google’s Gemini. Additionally, it examines two artistic projects by Elisa Giardina Papa and Trevor Paglen. The article argues for an aesthetic analysis that goes beyond debates over authenticity, highlighting instead the inherent complexity and weirdness of these digital artifacts by exploring how AI reshapes perceptions of reality. By invoking, among other things, theories of agnotology, it underscores the deliberate creation of doubt and the aesthetic construction of meaning in media landscapes shaped by AI. Ultimately, this study proposes that thinking (more) aesthetically about AI can enrich the understanding of contemporary visual culture, offering insights into how multiple realities and narratives coexist in “our” increasingly mediated world.

Key Words

aesthetic analysis; agnotology; generative AI; visual culture; unreason

1. Into the weirdness

In 1972, the Apollo 17 mission captured the iconic Blue Marble photograph, epitomizing the modern technological gaze and with it a comprehensible, entirely surveyed world.[1] With good reason, this image has left a lasting impression: calm, blue, and both breathtaking and understandable at once, it presents “our” blue planet Earth as a delimited aesthetic object, mastered by perception.[2] Many astronauts who have viewed the Earth from space report experiencing a profound shift in perception upon returning home, a phenomenon known as the overview effect.[3] As such, English astronomer Fred Hoyle presciently wrote in 1948 that “once a photograph of the Earth, taken from outside, is available―once the sheer isolation of the Earth becomes known—a new idea as powerful as any in history will be let loose.”[4] Indeed, images like the Blue Marble play a crucial role in shaping cultural ideas. However, I will argue, since its capture “our” view of the world has changed, particularly in relation to images and visuality. It has become increasingly difficult to maintain an aesthetic mastering position, “nominating the visible,” as Foucault would have it,[5] largely due to the increased complexity and weirdness of visual media content today.

In this article, I present a two-part argument: First, that the contemporary landscape of artificially generated media content requires aesthetic analysis and thinking, now more than ever, and second, that this aesthetic thinking should be even more aesthetic than we usually think it to be, that is, rejecting the bait of binaries like “true” and “false,” “real” and “fake,” and “reasonable” and “unreasonable” by instead focusing on the making (and unmaking) of meaning beyond rationality. Thinking aesthetically about generative AI (GAI) means recognizing and exploring the complex, layered narratives conveyed through media content and accepting that what might seem (hopelessly) fake or flat to “us,” is indeed the reality of someone else. Contemporary Aesthetics offers a valuable platform for addressing these challenges and for reflecting on how the discipline of aesthetics itself must respond. It is within this context that I present my thoughts on how AI not only alters the objects of aesthetic analysis but also transforms the methodologies and frameworks we use to engage with them. It is to this “we” I write.

Moving beyond the Blue Marble but staying within the realm of celestial bodies, Samsung’s Space Zoom-capable phones are a forceful example of this introduction of increased complexity and weirdness to the present. For years, this feature has been lauded for its ability to capture remarkably detailed photos of the moon.[6] However, a recent Reddit post exposed the extensive computational processing behind the images.[7] The post detailed a simple experiment where the user deliberately blurred a photo of the moon, displayed it on a screen, and then captured it using a Samsung S23 Ultra. Surprisingly, the resulting image showed clear details that were not present in the original. Following the introduction of the 100x Space Zoom feature in the Samsung S20 Ultra in 2020, concerns have emerged regarding the authenticity of these lunar photographs. Critics have alleged that Samsung overlays textures onto images of the moon, while the company asserts that it solely utilizes AI to “enhance details.” A 2021 feature by Input Mag highlighted this issue with the Galaxy S21 Ultra, noting that Samsung employs a “detail improvement engine function” to reduce noise and enhance details.[8] The core of the controversy lies in whether this function simply enhances blurry details through AI upscaling or if it employs a more intrusive method, potentially creating what could be termed “fake images.”[9] Unlike the Blue Marble, which offered a comprehensive view of Earth from above, Samsung’s moon images present a meticulously crafted and filtered gaze, grounded in our own situated perspective as we look up at the night sky. In contrast to the Blue Marble, these lunar photos represent a datafied perspective—the moon in high definition, superimposed onto the night sky above, stripped of any environmental variables. Samsung’s representation is not about capturing the moon in its natural state under various lighting conditions, but about refining it to its most aesthetically pleasing form. Samsung’s moons are flawless, “out-of-this-word,” yet the gaze they produce is also weirdly unreal.

Figure 2. The Space Zoom feature of the Samsung S23 Ultra smartphone in operation. Source: “Samsung ‘space zoom’ moon shots are fake, and here is the proof,” Reddit/ibreakphotos.

Moving into the realm of political communication, other examples of weird GAI imagery highlight a similar tendency. In recent political discourse leading up to the US presidential election, a notable trend has emerged: AI-generated images depicting a group of Black men purportedly supporting Donald Trump. While Trump has actively courted Black voters,[10] who were so important for Joe Biden’s election in 2020, there is no direct link between these young Black people and his campaign. Rather, the images are actively created to show Trump as popular in these communities. As such, these images are part of a growing trend of “disinformation” leading up to the November 2024 US presidential election.[11] Conservative radio host Mark Kaye and his team in Florida contributed to this trend by distributing a GAI image of Trump with a group of Black women. Kaye defends his actions, stating, “I’m not a photojournalist […] I’m not out there taking pictures of what’s really happening. I’m a storyteller.”[12] Indeed, Kaye’s self-identification as a storyteller rather than a photojournalist encapsulates the essence of his actions: Kaye does not capture the world as it currently appears, but bends it into shape using the narrative tools at his disposal. “Fake it till you make it,” as the saying goes; with the advent of generative AI, however, the power to “fake” has grown even stronger.

Another widely circulated AI image depicts Trump engaging with a group of Black men on a front porch. Initially posted by a satirical account known for creating images of the former president, the image gained attention when it was re-shared with a misleading caption falsely asserting that he had paused his motorcade to meet these young men. The post accumulated over 1.3 million views. While some users identified it as false, others appeared to accept the image as “authentic.”[13] Cases like these are particularly interesting because they challenge the already porous boundaries between subject and object, observer and observed, creator and creation, sender and receiver, and reality and fabrication. How do we as aesthetic theorists grasp and understand images like the ones introduced above? One possible response would be to adhere to the remnants of “reasoning” as we knew it, as a defense against the irrationality that characterizes what is commonly referred to as our “post-truth” era, thereby upholding traditional notions of rationality. Another impulse would be to reinforce the analytical frameworks of aesthetics, particularly in the Anglo-American tradition, by increasingly documenting and empirically demonstrating one’s own aesthetic interpretation.

Given the potential concern that avoiding these two inclinations may lead to naive materialism, positions of anti-intellectualism and anti-theory, or even a situation where unfounded speculation will distance us as theorists from more rigorous or “scientific” understandings of AI, I will proceed with caution. However, when I propose adopting a more aesthetic approach to understanding AI, it is partially an effort to transcend the stringent analytical framework of “academic” aesthetics and its close association with a specific rational impulse. This perspective underscores the importance of setting aside—or at least bracket—the issue of “realness” versus “fakeness,” and with it, “knowledge” versus “ignorance.” Unlike much of the media coverage surrounding phenomena such as Samsung’s moon enhancements or representations of “Trump’s” Black voters,[14] which tend to focus on the absence of clear authorship, reliable sourcing, or transparent methods, my interest lies elsewhere. I am not concerned with determining the truthfulness of these images or whether they were created using AI (or if such usage is transparently disclosed). Rather, my focus is on the aesthetic effects that emerge when we are confronted with uncertainty or doubt. In this context, the key question becomes: what does it mean for belief formation and knowledge production when factors beyond factual accuracy—such as emotional resonance or “vibe” of content—begin to carry more weight than the traditional indexical connection to an “objective truth”? What are the aesthetic implications of being constantly exposed to ambiguous and unreliable online content? And how can we best operationalize our aesthetic concepts to engage with a reality where knowledge is increasingly defined not solely by factual accuracy but by how content is felt and perceived?

2. Weaponized unreason

In a recent essay, Caroline A. Jones addresses what she calls the deliberate production of doubt.[15] With the term agnotology, she describes what she identifies as a particular form of irrationality, that is, deliberate manipulation of, for example, memory and reality, resulting in a manufactured “ignorance” that pervades contemporary society.[16] She points to how established concepts like rationality, intelligence, reason, and truth are being challenged, but also how their opposites—irrationality, stupidity, unreason, and falsity[17]—are being actively produced and aesthetically mobilized in today’s media landscape. Referring implicitly to Achille Mbembe’s critique of the constitutive division of reason and unreason within the colonial history of modernity, she writes:

Agnotology addresses a specific form of unreason in the calculational production of synthetic realities: the jiggling and loosening of memory, fact, and hard-earned facts that a produced ‘ignorance’ wreaks. How did we let ourselves become a ‘post-Truth society?’ We need to examine how the capital-saturated laissez-faire situation in which many of us live, addled by nationalism, haunted by totalitarianism, and dominated by the fictive persons (corporations) that nations have allowed to gain power in their midst, produces ‘truth effects.’[18]

A good example of an agnological case, used by Jones, and also Robert N. Proctor and Londa Schiebinger in their edited volume, Agnotology, from 2008, is the lawsuits against the tobacco industry in the US, which uncover 1960s internal memoranda directly and decisively advising to sow doubt despite mounting evidence of tobacco’s causation of cancer. “Doubt is our product,” the marketing executives directly wrote.[19] Other examples include the production of ignorance regarding art historical interpretation, more precisely art history’s whitening discourses, where alternative histories that could have been (or should be) pursued are “segregated,” producing ignorance in an otherwise shared historical record.[20]

Jones’ approach is highly fitting for the (deep-)fake examples discussed above: what more aptly describes the AI-generated images of “Trump’s” Black voters than a cynical and deliberate fabrication of doubt? While many voters may recognize the AI traits in these images and easily dismiss them as “fake,” for those who do not, it is this very doubt that becomes the “product”—a powerful tool capable of influencing their perception as they approach the voting booth. Likewise, a conceptual focus on the intentional manipulation of otherwise stable navigation points like memory and reality seems particularly well-suited to an analysis of Samsung’s optimized moon images, where the ambiguity of detail opens space for uncertainty. Jones’ perspective, particularly the lens of agnotology, offers a compelling framework. Yet, I will argue that this aesthetically focused analysis, especially in light of the introduction of AI, can and should be extended further.

This discussion centers on a premise fundamental to agnotology: for knowledge to exist, there must also be ignorance; and for meaning to be created, there must be a potential un-making of it. This suggests that when an individual (for example, a potential Black voter) encounters an image of Trump in a context that is not “real,” their experience may also be equally unreal and consequently ignorant. In contrast to this, I believe it is relevant to examine “the fake” as an equally important and world-building factor. Does the aesthetic experience depend on whether something is “fake”? If so, does this diminish the experience’s realness? Are the images discussed above—the sinisterly smiling presidential candidate and the AI-enhanced moon—necessarily flatter or more simplistic than images “of the real world,” or are we entering an age where the fake is just as powerful because it is felt and experienced so?

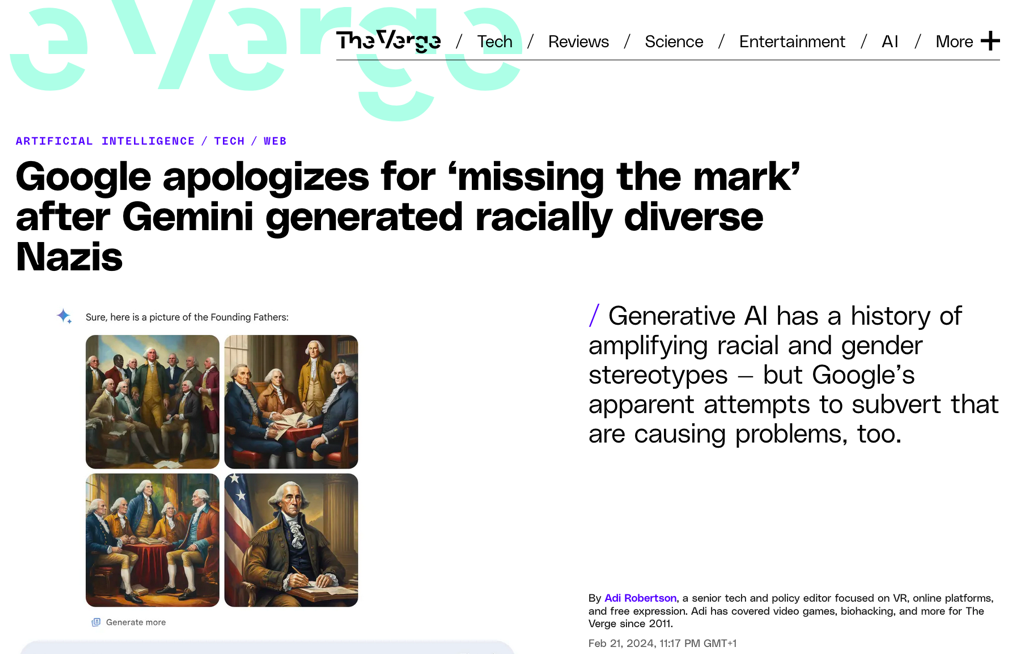

3. “Racially diverse Nazis”

Another similarly weird example is the case of Google’s generative AI chatbot (and prestigious flagship project) Gemini and the many problems Google faced when they introduced it.[21] The chatbot had not been out for long before users noticed that when they asked it to create representative images of, say, “Vikings,” “The Pope,” “German soldiers from 1943,” or “America’s Founding Fathers,” it produced surprising results: hardly any of the people depicted were white. Gemini had been fine-tuned to randomize markers of ethnicity and gender in images—for example, skin color, perceived gender, and clothing—thereby removing problematic associations between, for example, occupations and gender expression. When AI models are trained on extensive datasets, they exhibit broad and general emergent behaviors because the range of texts or images they attempt to re-construct is vast and varied. However, it is common practice to fine-tune these models towards more specific behaviors. For example, GPT can be fine-tuned to adhere to a dialogical, “chat-like” schema (transforming it into ChatGPT) or to avoid generating inappropriate content such as pornography or violence. Fine-tuning is achieved by retraining models on smaller, restricted, and deliberately biased datasets or by applying penalties to certain types of generations during training, thus deliberately warping the (statistical) associations between input and output data to increase the likelihood of producing the desired experience. In the context of Gemini, the fine-tuning was less about enhancing functional performance—such as resolution, realism, or fidelity—and more about catering to the sensitivities of a contemporary (Western) audience.

Consequently, one might ask: if bias is pervasive—embedded within technologies and socio-political ecologies—how effective is it to merely fine-tune a system to suppress its display? Why would it help to simply “shuffle” skin colors and textures, overwriting the historical context or “documentation” of racism inherent in existing images, and therefore, also in new, generated ones? This is agnotology at work: the deliberate manipulation of memory, facts, reality, and truth, resulting in a manufactured “ignorance.” The notion of the “racially diverse Nazi” epitomizes stupidity in Stiegler’s sense of the term[22]—an absurdity born from a “capital-saturated laissez-faire situation” that Jones describes. However, to deepen this critique, I argue, it is necessary to examine the precise production or operationality of this stupidity. This is where aesthetic analysis becomes crucial. These images are not simply “fake” or flat representations of the world; they indicate a shift in visual culture, actively shaping and reconstructing what “we” come to perceive as “our” reality. My concern, however, is not their lack of authenticity, but rather how blatantly fabricated they appear—making it almost incomprehensible that anyone could believe them. Yet the critical point is not that I have deciphered this absurdity from a “rational” standpoint. While these images may seem transparent to me, I can easily envision a Trump supporter accepting this narrative as truth; I can imagine this image constructing the world for someone else. Consequently, these images offer a vicarious glimpse into the world of others—a world that feels nearly impossible to share. This, to me, is what makes them deeply disturbing. While it may be tempting to simply opt for a “solution”—by altering skin colors, declaring an image as fake, identifying it as AI-generated, or labeling it as “political”—it is essential to explore the deeper aesthetic complexity involved in this flattening or faking at work.

The focus here is on understanding the imaginative aspects of these images, particularly their capacity to construct meaning, or their “worlding-capacity.” Thus, my first hypothesis is as follows: Thinking aesthetically about AI requires the preservation of diverse yet simultaneous narratives and realities, avoiding the imposition of a singular “reasonable” or “correct” version. In the ongoing debate surrounding AI-generated images, there seems to be a prevalent discourse that suggests more transparency—such as labeling an image as AI-generated—could provide a solution to the confusion or doubts these images generate. That certainty would dispel ambiguity. However, this view overlooks a deeper issue. Image manipulation is not a new phenomenon; tools like Photoshop have existed since the early 1990s. The notion that our problems can be solved if we just know is at best naïve. Thus, my second hypothesis would be that we, if we were to think (more) aesthetically about AI-generated images, would be able to move beyond the prevalent solutionism of tech culture. GAI images are inherently un-reasonable, spreading, buzzing, being everywhere at once.[23] They resist rational explanation or fixed meaning. To understand them, we must turn to aesthetics and use analytical tools that allow us to simultaneously engage with multiple narratives and “worlds.” As such, my third hypothesis is, that an aesthetic approach to AI requires engaging with the imaginaries of others, understanding the diverse worlds they inhabit. Part of this work involves agnotology: the critical study of how doubt is produced and weaponized, particularly against certain groups such as minorities. However, it also involves a genuine curiosity towards the perspective of the “other” as precisely other. This is not an argument for relativism; these imaginaries are not inherently good or right. Instead, the focus is on how meaning is aesthetically constructed across different perspectives, transcending the binary of “true” or “fake.” It is an approach that emphasizes the production of meaning, not just for oneself but for others whose appearance, preferences, privileges, or ideas may be vastly different.

4. Epistemological flattening

In his 2020 book An Apartment on Uranus, Paul Preciado argues that “we are going through a period of epistemological crisis,” catalyzed by a “paradigm shift of technologies of inscription, a mutation of collective forms of the production and archiving of knowledge and truth.”[24] Although this statement originates from a different context, I think it effectively encapsulates the situation within the field of AI and the context of the capital-saturated laissez-faire situation described by Jones. We are confronted with a crisis of understanding and sense-making that goes beyond notions of “post-truth,” and the discipline of aesthetics provides particularly suitable affordances for grappling with this crisis. Describing, analyzing, and understanding the processes of meaning-making, and unmaking, that occur “on the surface,” particularly in relation to the inscription technologies that Preciado emphasizes, aesthetics offers valuable concrete tools to discuss the sensory effects AI-generated content produce and the ways this is felt and experienced.

In her essay on “The ‘Cultural Technique of Flattening,’” Sybille Krämer introduces the idea that we have been socialized to believe that for thinking to be fertile, it must be oriented towards depth; that for thinking to be productive, it must search for hidden insights within or beneath. On the other side of the spectrum is the surface or the inscribed, superficial “skin” of things, that is deemed uninteresting and irrelevant.[25] Whereas intellectual activities such as traditional notions of interpretation are rooted in a privileging of “diving into the depth,” many contemporary phenomena call for precise attention to the surface, she claims:

We live in a three-dimensional world, yet we are surrounded by illustrated and inscribed surfaces. For modern civilizations, the use of inscribed surfaces is indispensable. Sciences, many arts, architecture, technology, and bureaucracy derive their complexity and distribution from the possibilities of using texts, images, maps, catalogs, blueprints, etc. to make visible, manipulable, explorable, and transportable something that is in many cases invisible or conceptual. Two-dimensionality became a medium of experiment and design, communication, and instruction. Everything that is, that is not yet, that can never be (like impossible, logically inconsistent objects), can be projected into the two-dimensionality of the plane.[26]

Krämer explores the epistemic, aesthetic, technical, and organizational roots of the cultural technique of flattening, presenting various examples such as the use of “flat” shadow lines in ancient sundials, Mercator’s world map projecting three-dimensional space into two dimensions, and both ancient and modern forms of algorithmization. She argues that this technique enables the analyst to systematically set up, see, know, and discuss complex phenomena across time and space, effectively transforming the world into representations that can be grasped and shared. Within the context of this article and of thinking (more) aesthetically about AI, Krämer’s essay is particularly relevant as it emphasizes the operational aspects of sense-making: we “know” through or via diverse apparatuses and techniques. Instead of merely lamenting the loss of complexity in inscribed surfaces—be it a deepfake or a “flat” moon photo—Krämer invites us to explore the layers of meaning that operate aesthetically at-the-surface.

The concept of operational images is another particularly relevant framework in this context, as it, like Krämer’s “surface-thinking,” stresses the importance of technological mediation in meaning-making. The term “operational images” draws directly from the foundational work of the filmmaker Harun Farocki, who pointed to the performative aspects of operative images, famously stating that they, rather than representing an object, “are part of an operation,” executing specific tasks such as tracking, surveilling, detecting, and targeting.[27] Drawing on Farocki’s work, image-theoretician A.S. Aurora Hoel explores how images influence human perception and actions, framing them as adaptive mediators that inform vision, instruct action, intervene in the world, and autonomously evolve.[28] In her essay, “Image Agents,” she underlines the perceptual doings of images, asking “how the introduction of a ‘foreign’ apparatus allows humans to see otherwise—sometimes even permitting an outsourcing of perception through the setup of an external system that ‘sees’ on our behalf.”[29] Responding to such a perceptual shift, she emphasizes that there is a pressing need for precisely humanistic—in this case, aesthetic—methodologies today. What is central in Hoel’s approach is precisely this process of making-visible and thereby knowable—and, one could add, the opposite. In the context of this article, the key point might be to consider what we are thinking “with” when using visual means like AI and how images like the ones discussed above change our way of seeing and making sense. “Along” which lines do we see, and do these lines make us know otherwise?[30] In the following paragraphs, I will discuss two artistic projects that in each their own way address the weirdness of meaning-making today.

5. Teaching machines to see

The first artistic project is Trevor Paglen’s From ‘Apple’ to ‘Abomination’ (Pictures and Labels), initially commissioned for The Barbican in 2019 and subsequently exhibited in other venues. This work explores ImageNet, the most widely used training set in AI, comprising over 14 million images categorized into more than 20,000 classes.[31] The installation consists of approximately 30,000 individually printed photographs, interrogating the complex relationship between images and their labels, echoing Magritte’s “Treachery of Images” in the era of machine learning, as Paglen formulates it.[32] As part of the exhibition, Paglen includes a framed reproduction of Magritte’s painting, annotated with bounding boxes identifying its contents—“a large white sign,” “black and white sign,” “a large green leaf,” “red and green apple.” Here, the process of labelling in its stupid literality points quite directly to the problems of AI. As models are trained to “see” the world, they are fed vast amounts of visual data sorted into various training sets. This “seeing” is visualized on the walls through concrete images, reflecting the value systems encoded within them. While some labels and images appear relatively innocent—such as “an apple,” “an apple tree,” and “fruit”—others reveal the trickier sides of this process: how does one visually represent an “alcoholic,” a “debtor,” a “drug addict,” a “homeless” person, or a “racist”?[33] The category “anomaly” includes individuals, many of whom are masked or in costumes, whose identities and classifications remain ambiguous.

Walking along the walls of Paglen’s installation reveals the heterogeneity of social media and uncopyrighted populist images that the creators of ImageNet have scraped from platforms such as Google, Flickr, Facebook, and Bing. These images, although used without permission from their creators, are far from hidden; rather, they precisely represent commonality of photographic documentation in daily life. However, the intention does not seem for viewers to perceive the images in this way. Instead, what is presented is a curated selection—samples of images and their associated labels that have been fed into machines to interpret “our” world. This curated collection embodies all classifications, taxonomies, and underlying assumptions, reflecting the full spectrum of societal projections onto the world.

In analyzing a piece like this, it is tempting to simply highlight the unreasonable nature of the training process involved in building an image database such as ImageNet, critiquing AI image practices for their simplification of a much richer visual field or questioning AI’s perceived limitations and the doubts it can create—drawing parallels to agnotology and its focus on ignorance. However, there is a deeper layer to consider within this project. For machines, the representational content of an image is equated with the object itself. For instance, to an AI, Magritte’s portrayal of an apple is not merely a symbol; rather it becomes functionally equivalent to an apple. Introducing these machine perspectives into our worlds fundamentally alters how images are perceived and interpreted. While ImageNet reflects a particular Western reality and its associated ideas, Paglen’s interpretation of ImageNet does not necessarily do the same. An important aspect of Paglen’s work lies in its exploration of alternative ways of seeing and understanding the world. It invites consideration of the various ways through which one could teach a person—or a machine—to see, including different myths, narratives, and potential realities. Utilizing Hoel’s formulation, one might examine the lines of sight established by this piece and what we are “thinking with” when using AI. Can these images be reimagined or reframed within alternative contexts? Similarly, drawing on Krämer’s formulations, one could ask: if datasets like ImageNet represent an artificial flattening of a much “deeper” culture or lifeworld, what could be set up, seen, known, and discussed as a result? If this constitutes a reduced inscription, what kind of apparatus does it then provide? What, or whose, reality is operating on the surface of these images? What narratives are produced through this process? And could alternative and potentially improved ways of living and thinking be imagined in this context?

6. Living with machines

A similar artistic project related closely to the weird field of AI is Elisa Giardina Papa’s Leaking Subjects and Bounding Boxes: On Training AI, from 2022.[34] Like Paglen, she addresses the ways in which machines are trained to see. But whereas Paglen shows an already established archive—taking his point of departure in ImageNet—Papa documents the concrete methods used to teach AI to capture, classify, and order the world. And whereas Paglen shows what is already built into the archive, Papa instead considers everything in daily life that defies these normative modes of categorization. Papa’s book presents images that she began collecting in 2019 while working as a human trainer for various AI vision systems. Among the thousands of training images she processed for her tasks as a “data-cleaner,” she collected those that seemed to resist the order of the AI system.

Segmenting, tracing, “bounding-boxing,” and labeling are key operations used to teach machines to categorize and separate, and the book is filled with examples like these ones—all the things that were too opaque and promiscuous (or the opposite), too deviating, or “false” to go into the database. Papa is herself very aware of the aesthetic and more philosophical discussions this kind of “learning practice” prompt.

In an interview with Zach Blas and Mimi Ọnụọha, both artists who also work with the contradictory logics of technological progress, Papa draws on works by Édouard Glissant and Fred Moten and Stefano Harney dealing with the epistemic problems of representation and classification.[35] If Harney and Moten talk about the “first right,” which is the right to refuse the choices as offered,[36] can we also imagine a right to refuse the either “in” or “out” of data classification? she asks. Papa continues:

Calling for the right to opacity for Glissant, I think, is about imagining and practicing a relationship with someone who is irreducible to a scale—or to a protocol of categorization—which she did not generate on her own. It is perhaps about bringing an end to the very notion of scale and classification. It is about insisting that we do not yet know what computation beyond an economic system driven by profit and dispossession could be, do, or look like. It is about insisting on imagining and cohabiting with computation and networks otherwise, and also imagining and cohabiting with the world otherwise.[37]

While bounding boxes and machine vision might initially appear to flatten the world by reducing complex images to mere patterns or standardized identifications, a more intriguing perspective, I argue, is to view them as “deep” and “meaningful.” These image tools offer insights into how “we” perceive and conceptualize the world, reflecting collective identities and perspectives. For instance, why is detecting apples prioritized in Paglen’s work? While apples may seem mundane to some, they might hold different significance for others. Object detection and bounding boxes, beyond functioning as mere training tools, can potentially stimulate new ways of “imagining and cohabiting with the world,” as suggested by Papa. What stands out in Papa’s exploration, particularly through examples of failed attempts at identification, is how these moments reveal the epistemic power inherent in images. Detecting what is present in an image reflects a specific worldview and reality, and often a white, Western, Californian one. Identifying these elements requires first being able to see them in order to make sense of them.

7. Thinking (more) aesthetically about AI

In conclusion, reflecting on the two artistic projects discussed, my two-part argument has been that one, the contemporary landscape of AI-generated media content requires aesthetic analysis and thinking, and second, that this aesthetic thinking should be even more aesthetic than we usually think it to be. The epistemological crisis brought on by AI challenges us as aesthetic theorists to examine the fundamental conditions of meaning-making—not merely focusing on production or infrastructure, which others thoroughly address,[38] but rather the basic questions surrounding perception and epistemology. Aesthetic analysis, I argue, offers a pathway to open the complex sensory experiences of seemingly fake content—not to dismiss or transcend them but rather to understand their operations, following Hoel’s approach.

Images like those of “Trump’s” Black voters require the complexity offered by an aesthetic approach to grasp how meaning is sensorily produced for a multitude of unknown receivers. While these images may be fake or flat in the sense that they were fabricated by AI, they have the potential to become reality, to become the world, for those who encounter them. This brings me to the conceptual framework of agnotology, which is key to understanding how AI-generated images intentionally produce doubt, ignorance, and ambiguity. However, I have argued, we must also broaden our understanding of the “receiver” and their capacity to distinguish between “true” and “false” and “real” and “fake.” Thinking (more) aesthetically about AI, we need to preserve multiple, simultaneous narratives and realities rather than imposing a single, “reasonable” or “correct” version of the world. As I have shown, the potential meaning of images is ultimately shaped by the eyes of the beholder.

This issue became starkly apparent during the scandal of Cambridge Analytica, the data analytics firm that worked with Donald Trump’s election campaign and the winning Brexit campaign, and harvested millions of Facebook profiles of US voters in one of the tech giant’s biggest data breaches.[39] These profiles were used to build a system that could profile individual voters to target them with personalized political advertisements. Crucially, the focus here was not on an external, universally agreed-upon reality, but on identifying which reality individuals believed in and then systematically altering it piece by piece with “fake” content. What is important to me in this context is not just labeling these phenomena as flat, fake, or “post-truth,” but recognizing that they constitute genuine realities for someone. Dog whistles offer a precise—and deeply aesthetic—illustration of this phenomenon.[40] These are messages that are perceptible to some, but not to others—deliberately so. In today’s media landscape, aesthetic communication has become increasingly weird and difficult to grasp, and perhaps the insistence on rationality as a response to this is misguided. For instance, when discussing Jacques Rancière’s distribution of the sensible, we should add that today it is not just who speaks and who is silenced, who possesses a voice and who is muted.[41] Today, multiple narratives and realities coexist from the start, with ambiguity designed into the message to simultaneously speak to different audiences in parallel. Some will discern the hidden message, hear the dog whistle, while others will not. Embracing an aesthetic perspective allows us to see these divergent narratives as they exist side by side, without imposing a mandate to merge into one singular “correct” reality. For some, “Trump’s” Black voters are undeniably real.

If AI and the political cultures surrounding it are challenging our ability to reason, is the solution to double down on rationality? It is understandable to want to hold firm to empirical knowledge in a time when certainty feels elusive. But perhaps this moment calls for a different response, particularly from humanists, aesthetic theorists, and cultural critics. Rather than retreating to empirical frameworks, we should recognize the power of aesthetic forms and formats—strategic ambiguities, double meanings, and sensory appeals—that shape meaning-making today. While the empirical may provide comfort in an increasingly uncertain world, I ask: Are we thinking aesthetically enough?

Maja Bak Herrie

mbh@cc.au.dk

Maja Bak Herrie is postdoc at The School of Communication and Culture at Aarhus University. She works within the fields of aesthetics, media theory, and the philosophy of science on topics such as computational technologies of vision, scientific imaging, photography, and artistic research. She is co-editor The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics.

Published on July 14, 2025.

Cite this article: Maja Bak Herrie, “On Deepfakes and Dog Whistles: Thinking Aesthetically about Generative AI,” Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 13 (2025), accessed date.

Endnotes

![]()

[1] Cf. Kelly Oliver’s description of how Blue Marble is alienating the viewer from the world, treating everything as an image: “To see Earth as an object floating alone in nothingness is to interpret the photograph within the technological frameworks that renders everything, even Earth itself, as an object for us, an object that can be grasped, managed, and controlled, an object ripped from its contextual home,” Kelly Oliver, Earth and World: Philosophy after the Apollo Missions (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 23.

[2] Donna J. Haraway wrote about this problem over thirty years ago, in “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” yet her description of the trained eye remains apt: “[T]he eyes have been used to signify a perverse capacity—honed to perfection in the history of science tied to militarism, capitalism, colonialism, and male supremacy—to distance the knowing subject from everybody and everything in the interests of unfettered power.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988), 581.

[3] Frank White, The Overview Effect: Space Exploration and Human Evolution (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 1998 [1987]).

[4] Fred Hoyle quoted by Emlyn Koster in “The First Photograph of the Earth from Space: Why was a 1950 Prediction so Prescient?” Museum of Science. June 5, 2023.

[5] Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, trans. Alan Sheridan (London: Routledge 2005 [1966]), 144.

[6] James Vincent and Jon Porter, “Samsung caught faking zoom photos of the Moon,” The Verge, https://www.theverge.com/2023/3/13/23637401/samsung-fake-moon-photos-ai-galaxy-s21-s23-ultra.

[7] Ibreakphotos, “Samsung ‘space zoom’ moon shots are fake, and here is the proof,” Reddit

https://www.reddit.com/r/Android/comments/11nzrb0/samsung_space_zoom_moon_shots_are_fake_and_here/ [accessed Oct. 21, 2024].

[8] Raymond Wong, “Is the Galaxy S21 Ultra using AI to fake detailed Moon photos?” Input Mag, January 29, 2021. https://www.inverse.com/input/reviews/is-samsung-galaxy-s21-ultra-using-ai-to-fake-detailed-moon-photos-investigation-super-resolution-analysis.

[9] For an in-depth discussion of the notion of “fakeness” and AI as a “technology of fakery,” see the work of Massimo Leone, e.g., “The main tasks of a semiotics of artificial intelligence,” Language and Semiotic Studies 9, no. 1 (2023), 1-13, or “The Spiral of Digital Falsehood in Deepfakes,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 36 (2023), 385-405.

[10] I acknowledge that there have been Black supporters of Trump, including rapper Kanye West, who publicly supported his 2016 campaign. However, this has not been the general trend among Black voters; see “Kanye West ‘would’ve voted for Trump’ in US elections,” The Guardian, November 18, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/nov/18/kanye-west-wouldve-voted-for-donald-trump-us-election.

[11] See, e.g., Jonathan Yerushalmy, “AI deepfakes come of age as billions prepare to vote in a bumper year of elections,” The Guardian, February 23, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/23/ai-deepfakes-come-of-age-as-billions-prepare-to-vote-in-a-bumper-year-of-elections.

[12] Mark Kaye quoted in Marianna Spring, “Trump supporters target black voters with faked AI images,” BBC, March 4, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-68440150.

[13] Spring, “Trump supporters target black voters with faked AI images.”

[14] See, for example, the comprehensive discussion of Samsung’s moon images, for instance in Wired, https://www.wired.com/story/samsungs-moon-shots-force-us-to-ask-how-much-ai-is-too-much/; in ArsTechnica, https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2023/03/samsung-says-it-adds-fake-detail-to-moon-photos-via-reference-photos/; or in The Verge, https://www.theverge.com/2023/3/13/23637401/samsung-fake-moon-photos-ai-galaxy-s21-s23-ultra. Or see BBC/Marianna Spring’s coverage of the story of the AI-images of Trump in “Trump supporters target black voters with faked AI images.”

[15] Caroline A. Jones, “Agnotology,” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 67, ed. Tobias Dias and Maja Bak Herrie (2024).

[16] The term ‘agnotology’ is already coined and explored in an edited volume by Robert Proctor and Londa Schiebinger; see Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 2008). Particularly Robert Proctor’s introduction to its epistemological use (not only how we know, but also how we do not) in this volume is helpful; see, “Agnotology: A Missing Term to Describe the Cultural Production of Ignorance (and Its Study),” 1-33.

[17] See Achille Mbembe, The Critique of Black Reason (Duke University Press, 2016) or the transcribed conversation between Achille Mbembe and David Theo Goldberg in 2017, David Theo Goldberg, “‘The Reason of Unreason’: Achille Mbembe and David Theo Goldberg in conversation about Critique of Black Reason,” Theory, Culture & Society 35, no. 7-8 (2018). See also the special issue of The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 67 on “Aesthetics in the Age of Unreason,” ed. Tobias Dias and Maja Bak Herrie (2024).

[18] Jones, “Agnotology,” 10.

[19] Jones, “Agnotology,” 11. Proctor & Schiebinger, Agnotology, vii.

[20] Jones, “Agnotology,” 11.

[21] Google Gemini received extensive criticism when it was released, see, for example, the news coverage by The Verge: Adi Robertson, “Google apologizes for ‘missing the mark’ after Gemini generated racially diverse Nazis,” The Verge, February 21, 2024, https://www.theverge.com/2024/2/21/24079371/google-ai-gemini-generative-inaccurate-historical; by Wired: David Gilbert, “Google’s ‘Woke’ Image Generators Show the Limitations of AI,” Wired, February 22, 2024, https://www.wired.com/story/google-gemini-woke-ai-image-generation/; or by BBC: Zoe Kleinman, “Why Google’s ’woke’ AI problem won’t be an easy fix,” BBC, February 28, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-68412620.

[22] Bernard Stiegler, “Doing and Saying Stupid Things in the Twentieth Century: Bêtise and Animality in Deleuze and Derrida,” trans. Daniel Ross, Angelaki 18, no. 1 (2013), 160-61, https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2013.783436.

[23] David Joselit, After Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 16-18.

[24] Paul B. Preciado, An Apartment on Uranus (London and Cambridge, MA: Fitzcarraldo Editions and Semiotext(e), 2020), 210.

[25] Sybille Krämer, “The ‘Cultural Technique of Flattening,’” Metode 1 (2023).

[26] Krämer, “The ‘Cultural Technique of Flattening,’” 4.

[27] Harun Farocki, “Phantom Images,” Public 29 (2004), 17.

[28] Kathrin Friedrich and A. S. Aurora Hoel, “Operational analysis: A method for observing and analyzing digital media operations,” New Media & Society 25, no. 1 (2023), 50-71. https://doi-org.ez.statsbiblioteket.dk/10.1177/1461444821998645.

[29] A. S. Aurora Hoel, “Image Agents,” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 61-62 (2021), 120-126.

[30] A. S. Aurora Hoel (aka Aud Sissel Hoel), “Lines of Sight: Peirce on Diagrammatic Abstraction,” in Das bildnerische Denken: Charles S. Peirce, ed. Franz Engel and Moritz Queisner (Berlin: Akademie Vorlag, 2012).

[31] Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen, “Excavating AI: The Politics of Training Sets for Machine Learning,” September 19, 2019, https://excavating.ai.

[32] Trevor Paglen, “From ‘Apple’ to ‘Anomaly’ (Pictures and Labels),” https://paglen.studio/2020/04/09/from-apple-to-anomaly-pictures-and-labels-selections-from-the-imagenet-dataset-for-object-recognition/.

[33] Mark Durden, “From ‘Apple’ to ‘Anomaly’,” LensCulture, 2019, https://www.lensculture.com/articles/trevor-paglen-from-apple-to-anomaly [accessed 21.10.24].

[34] Elisa Giardina Papa, Leaking Subjects and Bounding Boxes: On Training AI (Sorry Press, 2022).

[35] Papa, Leaking Subjects and Bounding Boxes, 369.

[36] Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Minor Compositions, 2013), 124.

[37] Papa, Leaking Subjects and Bounding Boxes, 370.

[38] Cf. Matteo Pasquinelli, The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence (London, England: Verso, 2023).

[39] Carole Cadwalladr and Emma Graham-Harrison, “Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach,” The Guardian, March 17, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election.

[40] Dog whistling is a type of symbolic communication in which members of far-right groups use seemingly innocuous language to express white supremacist views to a wider audience, all while avoiding detection, cf. Ian Haney López, Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class (Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2014). In this context, I use the term in a broader sense pointing to more plural forms of communication with more than one intended receiver.

[41] Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013 [2000]).